Out This Week

Hail, Caesar! (Universal, cert 12)

To describe the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! as a love letter to Hollywood is to understate the woozy, delirium these two middle aged men must have been in as they planned and put it together. But then their entire career has been marked by a regard, if not obsession, with the golden age.

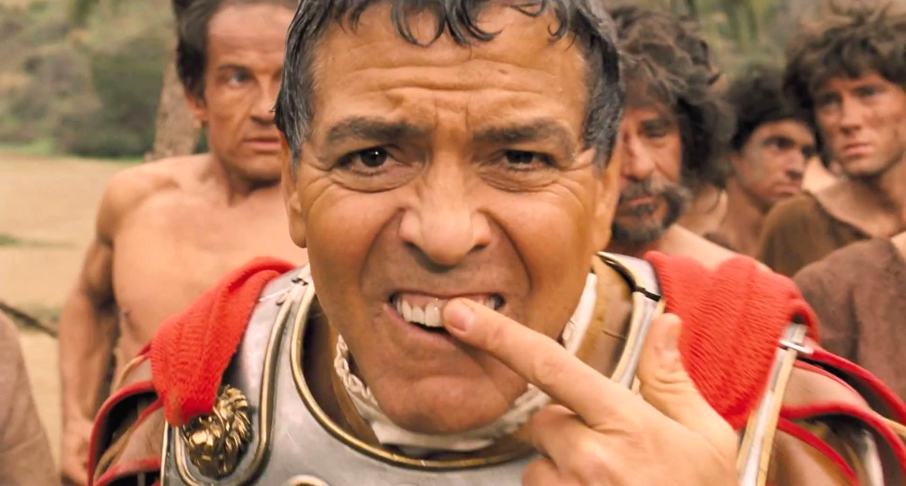

So what’s the plot? Josh Brolin plays a studio fixer trying to find a sword’n’sandal star (George Clooney) abducted by a bunch of blacklisted communists – the Hollywood Ten in all but name. And… er… that’s about it. Clooney is a Victor Mature/Richard Burton composite, a white-teethed naive who’s sculpted a career on his looks, though he’s keen to prove (if only to his kidnappers) that he has brains enough to take in what communism is, if that’s what they’re talking about.

Over on left field is Alden Ehrenreich (the film’s standout) as a hick actor suddenly asked to drop the lasso and play a suave high-tone lead, a part for which he is fundamentally unsuited. An Esther Williams type (Scarlett Johansson), more sexually active than her squeaky public image suggests. The supercilious, gay, foot-obsessed British director (Ralph Fiennes). A pair of gossip columnists, stand-ins for Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons (both played by Tilda Swinton and the only role(s) that doesn’t work). Channing Tatum as a Gene Kelly style hoofer.

And on they go. Glueing all these people together – though to be honest it’s a stew of tasty bites rather than a dish in itself – is superb cinematography that’s been colour graded to look like Technicolor, or in the black and white sequences steals from the aslant style of Welles, or Hitchcock at his most expressionistic.

The Coens repeatedly pull the same trick – one minute it’s a film about being in Hollywood, behind the scenes, at the studio. And then we’re suddenly inside a Hollywood film itself, the standout scene being Tatum’s On the Town style dance sequence, the sort of thing that would take days to film but is here presented as a finished item, as if it all happens just like that.

Don’t expect satire or dirt-dishing, in other words; there isn’t any – this is the Hollywood that people who go on studio tours want to see. Is Hail, Caesar! a great film? Nah. But it’s loads of fun, and great entertainment.

Hail, Caesar! – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

A Bigger Splash (StudioCanal, cert 15)

David Hockney’s painting of the same name is the inspiration behind the second collaboration between actor Tilda Swinton and director Luca Guadagnino, an Antonioni-esque farce, if there could be such a thing, that looks at the lives of people whose cultural ground zero is the late 1960s.

Hockney’s picture is a freeze-frame of a diving board, a pool, a modernist building and a splash where someone has just jumped in. It’s notably empty and the film also mines that feeling of empty existential ennui, of having just missed something, as lived out by aloof, Bowie-like rock star Tilda Swinton, now silent after an operation on her vocal cords and recuperating in Italy.

Into her life of sunbathing, fucking new beau Matthias Schoenaerts and waiting… waiting… comes old husband Ralph Fiennes and his daughter Dakota Johnson. Husband Fiennes, it transpires, is back for the woman he “gave” to Schoenaerts. And after a while it starts to look like the daughter is after the younger man, especially once she’s seen him strip down to his swimming trunks.

There’s great acting on a grand scale here, which lifts the film beyond its potential to be a farce in the style of Frayn or Fo or Feydeau. Fiennes in particular is aflame as the babbling ball of unmedicated mania, driving the drama as his character drives the people around him semi-mad.

Guadagnino and DP Yorick Le Saux, meanwhile, lay on the glamour, the upscale, savage Sicilian locations really helping deliver that feeling of bodies heated through to the point where gristle has given up being tough.

But maybe Walter Fasano’s editing is the best thing of all, particularly as the film ups its pace and heads into the final third, when the jealousy and intrigue get particularly machiavellian and everyone (no spoilers) becomes dangerously implicated in everyone else’s affairs.

It’s a much better film than the previous Guadagnino/Swinton collaboration, the more Visconti-like I Am Love. But though Guadagnino and screenwriter David Kajganich know exactly how to get into the heart of the things, they aren’t quite sure how to get out again. Antonioni had the same trouble, so that’s a quibble.

As a beautifully made essay summing up a generation, Guadagnino triumphs. And he’s nicer than some have been. This lot are dreadful and they’re self-obsessed, but at least they’re alive.

The Bigger Splash – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

Iona (Verve, cert 15)

Scott Graham’s film Shell was a wow-some bleak beauty that made much of the face of its star, Chloe Pirrie, who played a young woman living a life of restricted expectation up in the wilds of Scotland. Shell was the girl’s name, and the name on the sign at the gas station where she lived.

It’s a case of same/same with Iona – the name of the main character, played by Ruth Negga, and the small Scottish island she’s returned to with her son after some bad stuff has gone down in London. And it’s again an almost Thomas Hardy-esque tale of woe about a woman having a tough time of it in pretty surroundings, Negga’s fascinating features – as if giant eyes, eyebrows and mouth had been dropped onto a waiting face – doing the same this time round as Pirrie’s did last.

Graham is a good and perhaps a great film-maker and as soon as his film starts he’s stoking a sense of almost Wicker Man-like dread as he introduces one member of the community after another. What is Iona running from? Are her kith and kin really that pleased to see her? Why is her skin colour dark (Negga is half-Ethiopian) and is that a case of colour-blind casting or some part of the jigsaw? Is this tight-knit community perhaps a little too tightly knit?

Indeed it is, and as the story progresses Iona re-establishes connections with Daniel (Douglas Henshall), who might be a blood relative, or a former foster father, we’re not initially sure, and her son works up a fancy for Sarah (Sorcha Groundsell), a pretty local girl with paralysed legs and a look on her face that says, “save me from my suffocating parents.” And what teenage lad doesn’t like a girl who can’t run away? Hardy again.

As in Shell, Graham and DP Yoliswa von Dallwitz’s do a lot without shouting about it, one minute focusing on detail, another capturing mood, using the camera in a non-dogmatic way, as a tool to do a job. They craft art in the process. I can’t wait for Graham’s next.

Iona – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

The Chambermaid Lynn (TLA, cert 18)

Lynn (Vicky Krieps) is a flatliningly shy, depressed woman whose life means nothing to her. She has a McJob, cleaning hotel rooms and, being OCD, she’s really good at it. She’s also having half a fling with the greasy hotel manager, who reminds her “you know it’s over,” meaning their affair, before she unzips him anyway and gives him a blow job.

Voyeuristic to the point of going through guests’ stuff, trying on their clothes, Lynn’s life takes on new meaning when she’s caught on the hop one day and ends up hiding underneath a guest’s bed after a guest returns unexpectedly. It turns out that the guest has booked an S&M session with a local whore.

Not long afterwards, Lynn summons the courage to book the same woman, Chiara (Deutschland 83’s Lena Lauzemis), for a session too, perhaps hoping that maybe extreme pain will break through her carapace. And here The Chambermaid Lynn itself breaks through, having been so far one of those shadowless dramas about anomie, shot in the sort of flat style that’s been in favour in Germany at least since 2006’s grimly brilliant Requiem. And it becomes a film about love… of a sort.

That’s not to say Lynn’s anomie disappears. It doesn’t. But her condition intrigues Chiara, and in Lynn Chiara finds someone who is sheer, pure, artless, uncomplicated. And she likes that. Clearly it’s a contrast to her other clients. Quite how much Chiara likes Lynn’s mental state of being is what the film is about. Whether it works because of beautifully observed detail (a Benny Hill movement of a bare foot by Chiara’s client as a stiletto heel is driven into it), the vaguest suggestions that it’s dealing with Germany’s dark past (Lynn’s mother’s obsession with crochet and the repeated use of the word “Haken” (the crochet hook), as in “Hakenkreuz” – the Swastika). Or, less tenuously, because after the dry well of the opening scenes, The Chambermaid Lynn turns into the sweetest story of burgeoning emotion, and features an erotic seduction scene of exquisite tenderness.

It’s a slight drama, but a very winning one.

The Chambermaid Lynn – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

Warsaw 1944 (Kaleidoscope, cert 12)

In 1944 the people of Warsaw rose up against the Nazis. The Russians, who were on the outskirts of the city on their advance towards Berlin, instead of ploughing forward and liberating the Poles, hung back, and waited while the Nazis blew them to bits – saves us a job, kind of thing. This ambitious Polish drama tells the gruesome story of that massacre from the eyes of Stefan (Józef Pawlowski), a good-looking young man caught between two fine women – beautiful dark-haired city girl Kama (Anna Próchniak) and rich landed blonde Alicja (Zofia Wichlacz).

The film is as handsome as the casting, and if there is one problem with Warsaw 1944 (aka Miasto aka Warsaw 44) it is that it always looks like a film – big, choreographed, aesthetically just so – which slightly undermines the message that director Jan Komasa and his crew are trying to get across, which is that war is hell, and that the Warsaw uprising was a particularly hideous corner of hell. At one point an explosion kills so many people that blood, body parts and human offal literally rain from the sky. Nor are enough of the characters sketched in well enough before the chaos of the bombardment starts. I found myself going “hang on, which one is that again?”

In Komasa’s favour, he presents the mostly young Poles as a group relying more on enthusiasm than discipline (deliberate foreshadowing of the 1960s, maybe?) and he’s absolutely averse to the “death or glory” notion so prevalent in war movies. There is much death here, very little glory. The gore apart, it’s a very fine war movie in the Sunday afternoon style.

Warsaw 1944 aka Warsaw 44 – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

Versus: The Life & Films of Ken Loach (Dogwoof, cert 12)

That this documentary about Loach’s career is so timely is down to luck to some extent. Loach came unexpectedly out of retirement in 2015 to “fight the power” after the Conservative party, slightly surprisingly, won the UK general election, presumably when director Louise Osmond was at least at the research stage of this handsome overview.

Then serendipity was added when Loach went on to win the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year. I wouldn’t bother with Versus if you have no idea about who Loach is, or don’t have at least a vague timeline already in place about what he’s been doing since the mid 1960s. This is an appreciation and celebration rather than a definitive A-Z or 101 on the left-wing director.

Though there are plenty of biographical details, particularly of the early years when this son of an electrician stood as a Conservative candidate in a school election (Loach looks sheepish in interview at this point). It was only later, at Oxford, he admits, when he saw the sheer scale of the privilege and realised that no one else really had a chance, that Loach became politicised.

His career breaks into four chunks – the early years at the BBC where, heavily under the influence of the Czech New Wave, he learned his craft telling stories from the streets, shooting in sequence and relying heavily on his actors. He parlayed success on realist teleplays such as Cathy Come Home into a film career with the massively successful Kes.

Then there’s the Thatcher years of the late 70s and beyond, when Loach admits he simply didn’t know what to do, couldn’t get arrested and turned to making commercials (including, he admits with a shrug, one for McDonalds) and worked in the theatre.

Finally, as the Thatcher era ended, Loach’s career took an upswing with the likes of Riff Raff and Raining Stones. He’s been busy ever since, having made around 26 films since the early 1990s, though you wouldn’t know it from this documentary which moves at speed after the early years and starts to morph into a warm-up teaser for the new film, I, Daniel Blake.

Cillian Murphy and Ricky Tomlinson are among the names turning out among the more unfamiliar though more useful roster of writers and producers who have collaborated with Loach along the way. And there’s lots from Loach himself, most productively, who is as thoughtful, gentlemanly and open as others attest. It’s an admirable, short film, a lovely paean. Don’t expect any real engagement with politics and you won’t feel shortchanged.

Versus: The Life and Films of Ken Loach – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

The Seventh Fire (Metrodome, cert 15)

A downbeat documentary about life on the White Earth Indian Reservation, Minnesota, where Native American guys grow up, sell drugs and go to jail. We meet Kevin, a teenage lad with a terrible mullet hairdo, on the cusp of adulthood and keen to be a gangbanger like the bro’s. And we meet Rob, Kevin’s protégé and father figure, but a man who realises, as he’s about to go down for a three year stretch, that he’s already spent 12 years of his life in jail and it’s getting too much.

“Some guys like it in prison,” says Rob’s pregnant girlfriend with a touch of resignation, and if Jack Pettibone Riccobono’s documentary does anything excellently it’s this – it makes it transparently clear that when you have a poor education, few life chances and very low expectations, hanging around in jail isn’t much different from hanging around anywhere else. And having kids is what you do when you’re not on the meth pipe.

The philosophical nugget in this documentary comes from Rob’s realisation that he’s a Native American man with a whole set of traditions and culture that comes as a birthright. But this package now includes drinking, drug-taking and gambling. Tradition is a mixed bag, the old ways aren’t always the good ways and, he reckons, he can assemble his own version of “Indian identity”, bricolage style, though he doesn’t use the word bricolage.

Rob comes to this understanding thanks partly through exposure to the La Plazita Institute, a gang of Native American self-help evangelists who include hot rocks, teepees and sweat lodges among the more practical detox and counselling services.

But is Rob’s change of heart, joyous to watch, going to have any effect on the younger Kevin’s life? As the film ends, we see Kevin out in the woods, legs dangling from a metal railway bridge, dwarfed as a huge freight train rumbles across it, dangerously close to his back. The image is symbolic (and might be influenced by executive producer Terrence Malick) but Kevin’s future is not clear.

This slight, in many ways depressingly familiar film doesn’t offer solutions, but it does suggest the possibility of change.

The Seventh Fire – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2016