A movie for every day of the year – a good one

10 June

Dr Robert Smith takes his last drink, 1935

On this day in 1935, an alcoholic doctor called Bob Smith took his last drink. He was 56 at the time and had been drinking heavily since he was a college student, checking himself into drying out clinics periodically in an attempt to kick the habit. He had drunk through Prohibition, thanks to his access to medical alcohol and the profusion of bootleggers. And he’d drunk through nearly 20 years of his wife’s attempts to get him to cut down or stop drinking. It was his wife who encouraged him to attend meetings of the Oxford Group, a Christian organisation that believed in personal responsibility and moral re-armament.

It was here that Smith met Bill Wilson, a “recovering alcoholic” (to lock into the language of the almost universally accepted paradigm) who had helped a number of people give up booze. As a result of talking to Wilson, Smith gave up drinking, relapsed badly, had a few drinks on 9 June to stop the shakes. Then, on the morning of 10 June he had a beer to steady his hand while he performed an operation. It was the last drink he would take. The two men, known as Dr Bob and Bill W, went on to found Alcoholics Anonymous.

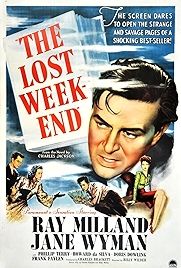

The Lost Weekend (1954, dir: Billy Wilder)

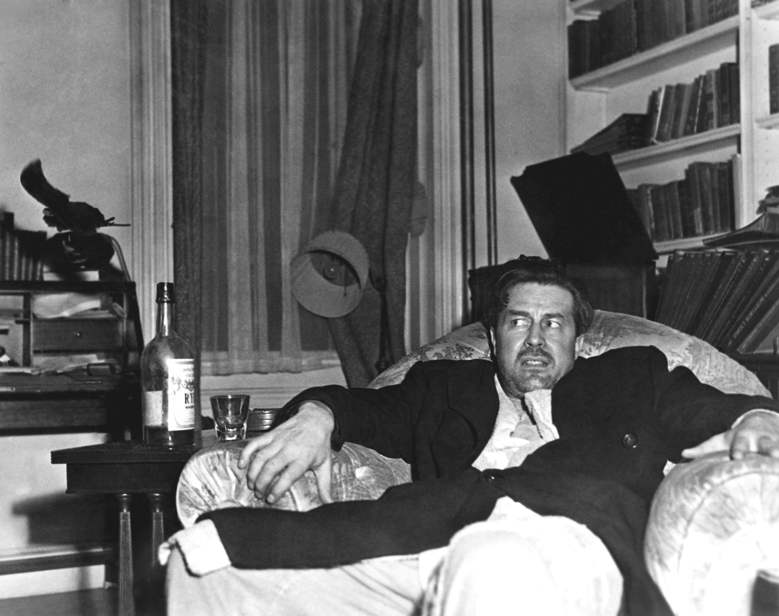

Ray Milland’s finest hour is also one of the best films about addiction ever made. Milland plays the writer who tries to ease his way out of writer’s block by easing his way into a bottle of hooch. Except he’s not drinking just one or two; he’s the sort who goes on gigantic benders, “bats”, as he calls them, a word that will later take on a more sinister hallucinogenic hue. The action opens at the New York apartment Milland’s Don Birnam shares with his brother Wick (Phillip Terry). And from the look on Wick’s face as he announces that he’s going away for a few days, we know that he’s expecting Don to hit the sauce as soon as his restraining presence is out of the way. Even though Wick has found and disposed of Don’s hidden stash, Don does, on money he steals from the cleaning lady, leading to a weekend of drunkenness and degradation that is mortifying to watch. Billy Wilder and writing partner Charles Brackett inject a devilish glee into most everything they do. In The Lost Weekend it manifests itself in the way that they keep shooting bottles and glasses as if they were beguiling sirens calling Don to his doom.

The film so concerned temperance groups that they petitioned the studios not to release it. They were worried that a depiction of a man driven to the very edge by his excessive drinking would somehow encourage drinking. And in the blue corner there was the drinks industry, who offered Paramount $5 million to destroy the negative. Paramount wavered and Wilder’s pleas to release the film eventually won them over. What the critics, who raved over it, and the public got was an impeccably crafted work, the black and white cinematography by John Seitz running from deep focus naturalism to wonky expressionism as Don Birnam slides towards the chasm. It’s a sparsely populated film – the bottle is Don’s real concern, not other people – the characters who stand out being those who come between him and his true love. Apart from Phillip Terry as the concerned brother, we meet Jane Wyman as the supportive girlfriend convinced that Don is sick, Howard Da Silva as the barman whose say-so gets Don a drink, and Frank Faylen as a tough orderly at the drying-out tank where Don ends up. Certainly Milland never produced a finer performance, fictionally channelling Wilder’s real concerns about the drinking of Raymond Chandler (Wilder and Chandler had worked together on Double Indemnity) into a compassionate portrayal of a man who’s bright, smart but fatally weak.

Why Watch?

- The Wilder/Brackett screenplay

- Milland’s best (some say his only) performance

- John Seitz’s groundbreaking cinematography

- Another great Miklos Rozsa score

The Lost Weekend – Watch it now at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014