A movie for every day of the year – a good one

12 December

Marconi receives the first transatlantic message, 1901

On this day in 1901, Guglielmo Marconi, one of the pioneers of long-distance radio transmission, finally proved that radio waves could travel really long distances. In 1894 he had started work on “wireless telegraphy” (sending telegrams without the need for wires, via Morse code) when only 20 years old, using his butler as a lab assistant – this was the butt end of the age of the gentleman scientist. He had soon worked out how to make a bell ring on one side of his room, wirelessly from the other. Impressed, his father had encouraged him to continue his experiments and gave him some money to do so. He did continue, though finding no take-up for his work in Italy, he travelled to London in 1896, where his fluency in English stood him in good stead, and at the Telegraph Office (now the BT Centre) in Newgate Street, London, he demonstrated the first public transmission of wireless signals. By 1897 he had transmitted Morse wirelessly over a distance of 6km. After this things moved rapidly and by 1899 Marconi was able to transmit from ocean-going ships. To turn his invention from something that obviously had huge benefit to a militaristic and maritime nation such as Britain to something that would have huge benefit for a wider public (and possibly himself), Marconi set out to transmit across the Atlantic – telegraphs at the time being transmitted via transatlantic cables running across the ocean floor. On 12 December 1901, Marconi reported that he had received the distinctive three-click Morse “S” signal in Cornwall, UK, transmitted from St John’s, Newfoundland, a distance of 3,500 kilometres (2,200 miles). No one since has been able to replicate the experiment with the equipment Marconi had at the time, and it is now generally accepted that Marconi either mistakenly heard the Morse signal, or faked his findings. Either way, the announcement of the achievement lent him enough heft to allow him to continue his experiments. By the following year he was transmitting radio signals across the Atlantic, the year after that President Theodore Roosevelt of the USA was able to send a message of greeting to King Edward VII of the UK. The radio age had arrived. The Bill Gates/Steve Jobs of his time, Marconi was still not 30 years old.

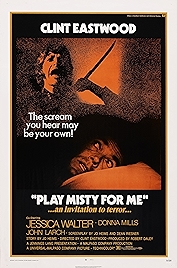

Play Misty for Me (1971, dir: Clint Eastwood)

Made just before Clint Eastwood would re-invent himself as Dirty Harry, Eastwood’s directorial debut is one of a select few about a radio DJ. It being an Eastwood film, starring the man himself, Dave Garver turns out to be a laconic kind of late-night DJ, the sort who plays romantic songs for lonely people and almost whispers between the tracks. Very intimate. The sort of DJ you could imagine the Man with No Name becoming, if you could get the cigar stub out of his mouth. And already playing, as he has repeatedly since in his career, with the Eastwood movie image, it’s this very quiet, dialled down, hushed aspect of the character of Dave that gets him into trouble, when one of the callers to his phone-in request slot starts to ask him for the track Misty by pianist Errol Garner (also one of Eastwood’s personal faves). Evelyn (Jessica Walter) phones often, always asking for Misty, and one night, after meeting her “accidentally” in a bar after work, he takes her home and does to her what she probably had been hoping he’d do all along. This is the big “you really should not have done that” moment in a film that then dives into territory more famously explored by Glenn Close in Fatal Attraction, as Evelyn proves herself to be a psycho bitch who pushes and pushes and pushes against this quietly spoken Californian in an age of peaceniks while the film faces the audience and asks us to guess when Dave’s going to snap. Lean as you like, perfectly cast and played, it was an auspicious start for Eastwood, a thriller with a brilliant sting in the tale which is so very wrong and yet so right.

Why Watch?

- Eastwood’s brilliant directorial debut

- Great music including Roberta Flack singing The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face

- Eastwood’s director-mentor Don Siegel cameos as a barman

- Jessica Walter is one of the great female psycho nutjobs of cinema

Play Misty for Me – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2013