A movie for every day of the year – a good one

13 May

Julian of Norwich’s visions, 1373

On this day in 1373, a woman who lived in Norwich recovered from an unspecified illness during which she had started seeing visions of Jesus Christ. The illness had been serious and she had not been expected to survive. As a result of making the unexpected recovery the woman became an anchoress (ie a hermit who lived in a cell attached – anchored – to a church). No one knows what her name was, but because the church she was anchored to was called St Julian’s, she became known as Julian of Norwich. She subsequently wrote a book about her visions, and the wisdom that Jesus had imparted while she was having them. She called the book Revelations of Divine Love, and it is the oldest book in the English language known to have been written by a woman. It was hugely popular. Over the next 30 years Julian would expand on her original text, the so-called Short Text, in a longer book exploring the theological implications of what she had learnt. In short, her writings re-aligned the figure of God from one of Old Testament rules, justice and retribution into a more New Testament God based on love, joy and compassion. She also held that God was both a father and mother, and that sin is the result of ignorance, not wickedness. She is best known for the phrase “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well,” which she claimed was spoken to her by God him (or her) self.

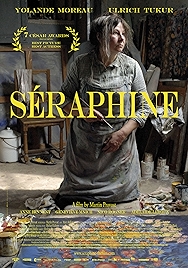

Séraphine (2008, dir: Martin Provost)

Here’s the story of the “modern primitive” artist Séraphine de Louis, aka Séraphine de Senlis, a naive French painter who died in a mental asylum in the 1940s and who spent her life skivvying to keep body and soul together, while painting in whatever time remained. This is a hard genre to get right, the biopic of the tortured artist, but director Martin Provost has done it. And it’s thanks in no small part to Yolande Moreau as Séraphine.

With a face and a figure more usually seen in comedies (she was in Amélie and Micmacs, by Jean-Pierre Jeunet), Moreau puts a human spin on a character who could easily have been forbidding and remote. Instead Moreau’s Séraphine is a harmless clumpy frump, a woman who uses mud, blood and wax stolen from church to make her pigments for the pictures she paints. By day an awkward, shy woman who might wash bed linen in the river, by night Séraphine disappears into euphoric religious raptures while she creates. Provost and Moreau spend a long long time getting this character established in deed rather than word, letting us come to an appreciation of Séraphine as a woman and of her style as a painter – her flowers and fruit drawn from nature, with something of Henri Rousseau and Van Gogh about them. Then comes the catalyst in in her life: Ulrich Tukur as Wilhelm Uhde, the German art dealer who is hiding out in a remote French village ostrich-like as the First World War approaches, and whose patronage changed Séraphine’s prospects – for good and ill.

As for accuracy, true-to-lifeness, that’s up for grabs. What makes Séraphine unusual as a film about an artist is that it goes into great detail about the artist’s working methods. The art itself is often the last thing on a biopic’s mind; think of Anthony Hopkins in Surviving Picasso or Salma Hayek in Frida, about Frida Kahlo, and tittle-tattle rather than insight into the life artistic seems to be what’s on offer. But more than the art, Provost and Moreau seem to be making a larger point about artists as a whole – even borderline insane ones, perhaps especially borderline insane ones. That in a secular world these holy innocents have taken the role of saints. And in Séraphine, we have the perfect intermediary.

Why Watch?

- Yolande Moreau’s remarkable performance

- A fascinating portrait of a real person

- Plenty of shots of Séraphine’s work

- Winner of seven Césars, the French Oscars

Séraphine – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014