A movie for every day of the year – a good one

15 October

Friedrich Nietzsche born, 1844

On this day in 1844, the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche was born in Röcken, near Leipzig, Germany. A philologist initially, Nietzsche was a university professor at the age of 24, in Basel, where he counted Richard Wagner as one of his friends. Within ten years, because of a variety of illnesses, both mental and physical (one of which was possibly syphilis) Nietzsche resigned from Basel and took up life as an independent philosopher, choosing to spend his winters in warm southern European towns, such as Genoa, Nice and Turin. It was during this time that he produced the bulk of his work, Daybreak, The Gay Science, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morals. Among the words and phrases we commonly still use, which derive from Nietzsche’s work, are the “There are no facts, only interpretations”, “God is dead”, “What doesn’t kill me makes me stronger” the “Will to Power” and he came up with the idea of the “Superman” (Übermensch). Nietzsche hated the left and also hated anti-semites, yet ironically has been taken up avidly by both, who see him as a philosophical cure-all, in the way that generations of students have seen him as a guarantor of intellect, earnestness and cool.

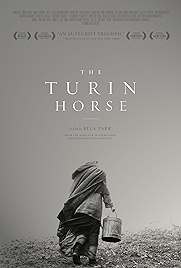

The Turin Horse (2011, dir: Béla Tarr)

On 3 January 1889 in Turin, Nietzsche remonstrated with a man who was beating his horse. Throwing his arms around the horse’s neck to protect it, Nietzsche collapsed. It was the last sane act he would ever perform and indeed he never recovered, though it took him 11 years to die. The great Hungarian director Béla Tarr’s farewell film, so he says, begins with a rolling intertitle which details the Nietzsche/horse story. It then cuts to two hours of arthouse dirge, a protracted series of tableaux of escalating bleakness that may well be an analogue of a life lived without hope. Black and white, almost wordless, a relentless wind howling the entire time against a soundtrack of ponderous, discordant music, the film focuses on an old farmer who has lost the use of one arm, his daughter and their life of unrelenting tedium. Each evening the same ritual is repeated, when the daughter cooks a potato for each of them and they fall on the food as if it were the first time they had eaten in months. For entertainment they stare out of the window. Not much breaks this cycle. At one point a yokel turns up, only to tell them that the local village has blown away. At another point some gypsies turn up – is something going to happen? No, they disappear quite quickly. Meanwhile, the silent pair’s only animal, a horse, appears to be dying in the stable. You will never have seen so many leaves blown through a wind machine as you’ll see in The Turin Horse. You will rarely have seen a film in which so little happens. Even cinematographically this is a film in which there isn’t a lot of movement. There are only 30 long, static shots (Fred Kelemen, Tarr’s DP, is clearly cut from the same cloth as Tarr and his co-director wife, Agnes Hranitzky). It’s hardly Hollywood. And yet it is an oddly gripping film. What the hell is going on? Is anything going to happen? In what way is Tarr going add another level of misery? Is he ever going to crack a wink? No. He doesn’t. Personally, I’m convinced The Turin Horse is a comedy, a kind of arthouse superhelping of meta-misery. Even if it is, it’s a very dry kind of humour Tarr is exhibiting. Must be those long, cold, dark Hungarian winters. A classic.

Why Watch?

- The last film of a Hungarian master

- A much easier intro to Tarr than his seven-hour long Sátántangó

- A key influence on the remodernist movement

- If you’ve seen Gus Van Sant’s Gerry and wonder who he got the idea from…

The Turin Horse – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2013