A movie for every day of the year – a good one

18 June

The battle of Waterloo, 1815

On this day in 1815, the battle of Waterloo was fought, in what is now Belgium. On one side was a French army under the command of Napoleon Bonaparte, on the other the forces of the Seventh Coalition – Austria, Prussia, Russia and the UK – but most notably Prussia and the UK, under the command of the Duke of Wellington. The battle marks the end of Napoleon’s adventure in Europe, which had seen him expand the natural borders of France into Belgium, Holland, Italy and Germany, conquer and rule another set of nations around that central core (Spain, Naples, parts of Poland), and then finally strike alliances with the remaining powers in Europe (Prussia, Austria, Russia). He had abolished the Holy Roman Empire, swept away the remnants of the feudal system (which made him very popular with some people, not with others), standardised weights and measures, and expanded the libertarian aspects of the French Revolution across Europe. Back from initial exile on the isle of Elba, Napoleon had been fighting and winning a series of small battles against the Prussians and British in the previous few days as he drove towards Paris. Waterloo was the latest of them.

It didn’t last long – Napoleon had 69,000 men and attacked Wellington’s forces at noon. Wellington’s forces (67,000 men) stood firm. In the evening 48,00 Prussians arrived and broke through Napoleon’s right flank; Wellington seized the moment and thrust forward, scattering Napoleon’s forces as the went. The coalition troops continued their march on to Paris, where they restored King Louis XVIII to the French throne. Napoleon fled, originally intending to sail to the United States, but ended up surrendering himself to a British captain.

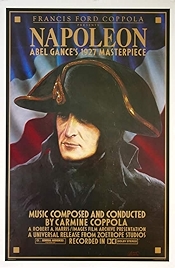

Napoléon (1927, dir: Abel Gance)

Abel Gance’s silent 1927 biopic about the life of one of France’s most famous sons stood, in the opinion of the New York Times in 1927, no chance of holding a candle to the man himself – “No camera is large enough to show so gigantic a figure without distorting the perspective, no lens exists with focus deep enough etc etc”. The original review continues in this manner for a while but does eventually point out that this does not mean the film is a failure.

In fact James Graham’s report from the premiere in Paris heaps praise on director Abel Gance, his poetic vision, his artistry, his technical command, his avoidance of melodrama (for the most part), summing up with the verdict that the film is “a triumph of motion picture art”.

Which is all very well, but had Mr Graham seen Gravity? In other words, does Gance’s Napoléon stand up today? The answer depends on the version you watch. The truncated versions, some running only 75 minutes, are simply too short, and are little more than a series of poorly connected scenes from a life. But longer versions, which clock in at anywhere from 235 to 330 minutes (yes, over five hours) justify the position on Sight & Sound’s Top 250 Films list (in the 2012 poll it’s number 144, two ahead of The Wizard of Oz).

It earns that place by virtue of its technical achievement alone – Gance effectively invents CinemaScope in Napoleon, yoking together three movie cameras to shoot wide triptychs at key points of the film. The key points being the battles, of course. The film follows Napoleon from boyhood throwing snowballs at his schoolboy tormentors, shows him reinvigorating the battered French army, then on to glory after glory, culminating in his Italian campaign of 1796.

The focus is on the positive – this is Napoleon the spreader of revolutionary values through Europe, not the despot who set himself up as emperor and starts aping the regimes he has just toppled. But Napoleon is maybe best seen as a prime exhibit in the case for silent film being its own art form, not some hobbled precursor to the talkies. Gance’s style is dynamic, thrusting, quick edits and fast camera movements combining to give the impression of energy and progress, the frequently tinted frames adding patriotic flag-waving scenes in red, white and blue (and sometimes all at the same time in the Polyvision sequences). As for Albert Dieudonné’s performance as Napoleon, it is as iconic as Mount Rushmore. God given is the translation of Dieudonné – you could say that about the whole film.

Why Watch?

- An entirely iconic masterpiece

- Gance’s innovations

- Gance’s mastery of editing

- Albert Dieudonné’s definitive performance

Napoleon – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014