A movie for every day of the year – a good one

19 December

Birth of Leonid Brezhnev, 1906

On this day in 1906, the very last old-school leader of the USSR was born.

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev was born into Tsarist Russia, the son of workers. Thanks to an education at a technical school he became a metallurgist, joined Komsomol (the Communist youth movement) and started to make his way in the party, becoming a political commissar in a tank factory by the age of 30, and eventually party secretary in Dnipropetrovsk, a Ukrainian city intimately connected to the arms industry.

As a result of Stalin’s purges in the late 1930s, Brezhnev advanced rapidly into suddenly available positions. He was tasked with important work in the Second World War and acquitted himself well.

Brezhnev had been Nikita Khrushchev’s protégé since the early 1930s, and as Khrushchev’s star rose, so did Brezhnev’s. Stalin appointed him a member of the Presidium in 1952. In 1953 Stalin died and Khrushchev took over. Brezhnev’s time had come.

When Khrushchev was removed in 1964, partly as a result of Brezhnev’s manoeuvrings, Brezhnev took over, on a ticket of restoring collective leadership of the USSR.

However, by a series of quiet strategies he managed to collect power around himself.

Brezhnev’s era was marked by the suppression of Khrushchev’s political liberalism, a strengthening of the power of the KGB and the restoration of the cult of the leader.

Some experiments were made with free-market principles (in Hungary, for example). Until 1973 the USSR economy continued to expand rapidly (as it had done since the Revolution) but after 1973 spending on the arms race as well as a general intransigence of the leadership began to act as a drag on the economy – the standard of living started to fall, services began to deteriorate. By that time Brezhnev had also become a pill-popping drunk.

For the last seven years of his life Brezhnev was not a well man – he suffered strokes and heart attacks, had emphysema, gout and possibly leukaemia. He was brought back to life several times before, in 1982, dying of a final heart attack aged 76.

Having presided over a Kremlin increasingly full of old men while he lived, Brezhnev was succeeded by Yuri Andropov, aged 70. Yuri Androprov only lasted 15 months before he too was dead. 13 months after that Andropov’s successor, Konstantin Chernenko, was dead too, aged 73.

Enter Mikhail Gorbachev, aged 54.

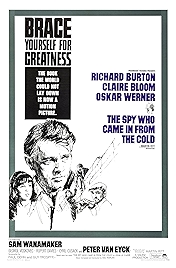

The Spy Who Came In from the Cold (1964, dir: Martin Ritt)

Written by a former spy, John Le Carré, and shot in a style borrowed from British kitchen-sink miserablists, The Spy Who Came In from the Cold is probably the best Cold War film ever made, not least because it eschews the glamour of spying and spies – no James Bond heroics. In fact there aren’t even the tawdry delights of tinned mushrooms, one of the small luxuries available to The Ipcress File’s Harry Palmer.

This is spying as nasty, brutish work, where your own side is so out of control of the situation that there’s a good chance you’ll die as a result of their efforts.

It is also, probably, the best screen performance by Richard Burton, as the spy being courted by the other side because they believe he might be happy to change sides now he’s been demoted to a desk job. But the communists are worried that he is in fact a double agent, a notion that the film spends some time being a bit cagey about too.

It’s a good one, but I’m not sure that plot is really what this film is about. Atmosphere seems more director Martin Ritt’s concern – in bleak meetings on park benches or in shabby hotel rooms, or simply in shots of Burton’s Alec Leamas drinking himself senseless in his shabby bedsit, Ritt is after a feeling you didn’t get in spy films of the era, of compromise, muddy morality and of the end justifying the means.

In the centre of this we have Burton, the embodiment of that atmosphere, craggy, hollow-eyed, a husk. The decision to shoot in black and white always requires justification, but none is required here: this is a drab world of buses and drizzle, of barbed wire and rough grey blankets, and cinematographer Oswald Morris’s noirish tones are exactly what is required.

And so, from a different perspective, is Claire Bloom, playing the sweet idealist who believes that communism might actually be the solution to the world’s problems. Not because she’s a communist but because the alternative, believing in nothing, is what makes people like Alec Leamas.

Why Watch?

- The greatly under-rated director Martin Ritt (The Sound and the Fury, Hud)

- Oswald Morris’s cinematography

- A support cast including Oskar Werner, Cyril Cusack, Michael Hordern

- First cinematic appearance of Le Carré’s spymaster George Smiley

The Spy Who Came In from the Cold – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affliliate

© Steve Morrissey 2013