A movie for every day of the year – a good one

20 July

László Moholy-Nagy, 1895

On this day in 1895, the painter, photographer and member of the Bauhaus school Moholy-Nagy was born in Bácsborsód, Hungary. Born László Weisz, he changed his Jewish surname to a more Hungarian one after his Jewish father left the family, and took Nagy (pronounced Nodge), later adding Moholy after the town of Mohol, where he grew up. He studied law in Budapest before fighting in the First World War, during which time he became involved with progressive artists and the “Activists”. He studied art for a while after the war, in 1919, before heading to Berlin in 1920. By 1923 he was teaching at the Bauhaus, where he expanded his interests (and teaching) into the fields of photography, typography, sculpture, printmaking and industrial design – most of them not prestige fields. He resigned from the Bauhaus and became a freelance designer, working in theatre, book design, advertising and film. He moved to London when the Nazis came to power and lived with Walter Gropius for a while, became a photographer of contemporary architecture for Architectural Review (commissioned by future poet laureate John Betjeman) and also worked on producer and fellow Hungarian Alexander Korda’s film Things to Come as a special effects designer. He then moved to the USA, where he became the director of the New Bauhaus in Chicago. This closed after a year, but Moholy-Nagy went on to become the head of the Institute of Design, later part of the Illinois Institute of Technology. He died in 1946 of leukaemia, leaving behind a wealth of photographs, kinetic sculptures and a lively interest in constructivist-flavoured functional design that influences people to this day.

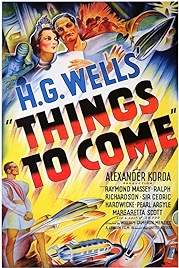

Things to Come (1936, dir: William Cameron Menzies)

Things to Come takes us right back, not just to 1936 when it was made, but almost to the dawn of modern sci-fi. Written by HG Wells (The Time Machine, The Invisible Man, War of the Worlds) – who was often on set during shooting– it is also one of the most fully realised modernist films that we still have.

None of the work László Moholy-Nagy did on the sets was ever used, but the influence of fellow modernists is obvious – this is a hymn to progress, albeit with a very 1930s flavour: it’s keener on authoritarian central control than any futurist film made these days would be.

Plotwise there isn’t very much to speak of. We start off in the present, in 1936, where life is more or less peaceable. Then we jump on twice. First a few decades where war is total and civilisation has broken down entirely, leading to a brutish dictator taking control. And then again to 2036 and the beautiful, designed environment of calm and order, whiteness everywhere, light, air. It all looks a bit like Albert Speer’s visions of the future dreamt up for Hitler, but no one working on Things to Come could have known anything about that then.

Looking at it now, some things seem shocking in a way they wouldn’t have been then. It is British, for starters. Unabashed straightforward non-ironic sci-fi could only be American (or Soviet) in future decades. But in the 1930s, still possessing the largest empire the world had seen, Brits felt confident enough to predict that the world a hundred years hence would be shaped in their image. Hence Everytown, the futurist paradise, a place full of people speaking with the sort of clipped accents that now belong in an audio museum. Then there’s the acting, done as if each speaker is standing on a stage and shouting to the gods.

A lot of those present – Raymond Massey, Ralph Richardson, Edward Chapman – were theatre actors originally, but even so their performances reek of the artificial. But then maybe that’s only to be expected, given the tone of the thing. Portent was the dominant tone of sci-fi, right up until the 1970s. Think of The Day the Earth Stood Still, or Star Trek or 2001, all earnest as hell.

No, the thing to take away from Things to Come, apart from the fact that it predicted the horrors of the Second World War, is its amazing high modernist look – huge plazas, cities roofed in, monorails, geometric grids, flying walkways, the design trademarks of architects such as Norman Bel Geddes, Le Corbusier, John Portman, Mendelsohn & Chermayeff, in materials such as glass, steel and new plastics, a mix of European Modernism and the American International Style that hasn’t been matched.

Things to Come predicts the world of the shopping mall and the international airport terminal, with a progressive, cheery vision of the future where people just conform. It all now looks deeply suspect. And if that doesn’t make something worth watching…

Why Watch?

- The future – in 1936

- As close as we can get to HG Wells on film

- The modernist sets

- A cast of thousands

Things to Come – Watch it now at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014