A movie for every day of the year – a good one

6 March

Alan Greenspan born, 1926

On this day in 1926, the economist Alan Greenspan was born in New York City. His father was a stockbroker and analyst but Alan initially seemed to be heading towards a career in music, studying clarinet at Juilliard, playing with Woody Herman’s band, before switching to economics. He gained a bachelor’s and a master’s in economics before becoming an analyst, then a consultant. In 1974 he was appointed by President Gerald Ford as Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. Greenspan was a member of the Group of Thirty (wise men of economics, essentially) in 1984 before becoming chairman of the Federal Reserve in 1987, a position he held until just before his 80th birthday in 2006. Greenspan was a monetarist, a rationalist and a follower of Ayn Rand, but he was first and foremost a numbers man. When the figures didn’t match the theory, it was the theory that was wrong. He admitted in congressional testimony in 2008, after the worst financial collapse since the great depression, that his belief in deregulation had been “shaken”.

Margin Call (2011, dir: JC Chandor)

Director/writer JC Chandor really seemed to come out of nowhere with this debut, a remarkable thriller about the financial collapse – who’d have thought such a thing possible – that boils everything down to one fateful night in one investment bank, where some geeky junior has suddenly realised that the numbers don’t add up and that fiduciary apocalypse beckons. The junior is a junior actor – Zachary Quinto – who spends the film accompanied by his more doltish chum Seth (Penn Badgley) who is there to explain any of the sticky stuff, of which there is remarkably little.

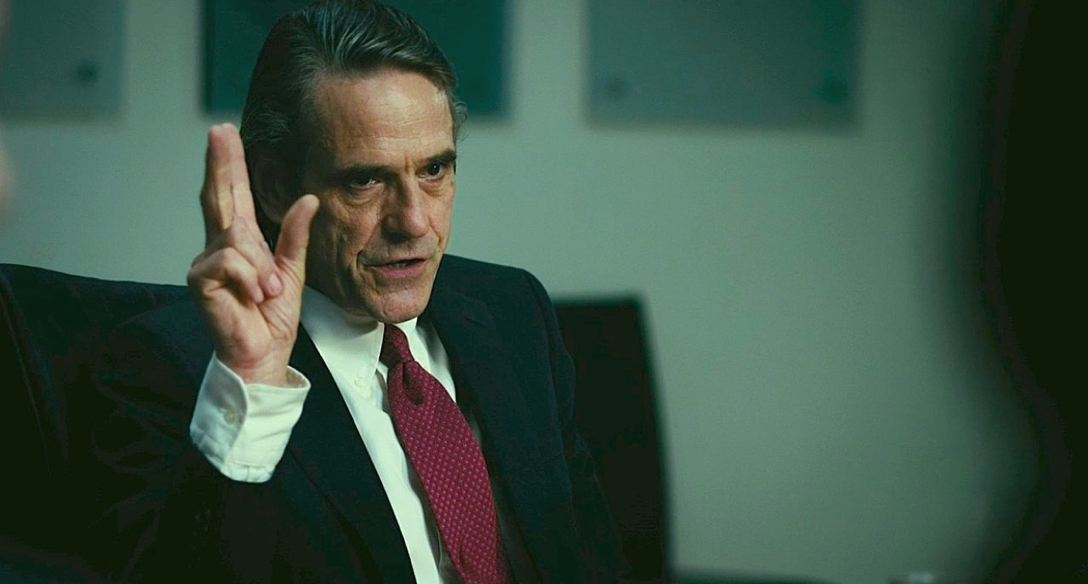

The structure of Chandor’s film is remarkably simple – over the course of the night Badgley, Quinto and whoever they have picked up en route, are bussed from one meeting to another, constantly moving up the pecking order, from daily offices to executive suites, the plebeian to the patrician, the outer to the inner sanctum, up, up, up they go. At each level of this glass and steel edifice everyone has to get used to breathing a slightly more rarefied air. And there are a lot of levels. This is a film where all actors concerned seems to understand that what they’re doing is momentous; everyone is pulling out the good stuff. Early on we meet Stanley Tucci, as the lowest level of the big players, the guy who is fired in the opening scenes, shrugs and then goes home. Paul Bettany is the tic-driven, adrenaline-snorting salesman. Kevin Spacey is his superior, the first of the financial big players to make our stand-ins, Quinto and Badgley, a little loose bowelled, and the last who has any humanity (his dog is dying at home) left inside. Demi Moore plays another formidable executive, a woman in a man’s world who wears the glass ceiling almost as jewellery and so is not as frightening as the next guy up the ladder – Simon Baker, a brash street guy done good, a man who drank greed is good with his mother’s milk. We think we’re at the top already but then we go up one more, to meet Jeremy Irons, in the sort of role that Laurence Olivier would once have played, all affability and stiletto, the CEO of this mighty financial empire who has arrived at dawn in a helicopter like a bird of prey.

It’s with Irons that the full dastardly logic of self-preservation plays out – he takes decisions that he knows will cause the market to collapse, but they will ensure that his firm will survive. It’s the small guy who is going to suffer, the same small guy who is left out of the reckoning when bonus season comes around. Chandor doesn’t rely on his viewer having even a slender grasp of economics to make this film work – it’s essentially a human drama about minnows awed by sharks. And doesn’t this world of big money look fantastic – the workers reduced to faceless drones while the fixtures and fittings have real character. A perfect film? Nearly. Maybe someday somebody will just tighten up the last third a touch, remove one of the too-many speeches that defend the way money guys do things, so it runs with the same pitiless speed as the first two thirds. Or maybe I’m just nitpicking.

In a very short list of great films about money (Greed, Glengarry Glen Ross, Boiler Room, both the 1928 and 1983 L’Argent spring to mind), this is the best film about the 2008 crash, no question.

Why Watch?

- The arrival of writer/director Chandor, fully formed

- A great cast on top form

- A thriller from finance – remarkable

- John Paino’s formidable production design

Margin Call – at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014