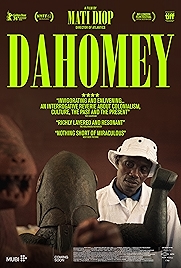

Doing very little but saying quite a lot, Mati Diop’s documentary Dahomey tracks the return of a number of artefacts from France to Benin in West Africa, which was known as Dahomey when they were first appropriated – looted, if you prefer.

The fairly short film divides up into three distinct chunks. In the first, Diop’s cool, fly-on-the-wall camera follows the action as the items – wooden carvings of deities, thrones and so on – are crated up, watched over by Calixte Biah. An elegant man with a grave expression who assesses the artefacts for damage, Biah notes the condition (cracks, flaking paint etc) of the treasures and supervises as they are carefully secured with fabric ties and sealed in their crates ready for shipment.

In part two the temperature rises slightly – more than just literally – as the relics arrive back in Benin, to dancing in the streets, construction workers pausing their activity to watch as the procession of trucks goes past, exultant newspaper headlines (“Historique!”), the ceremonial welcome from dignitaries in fine clothes, the holding room where the recent arrivals are held, dehumidifiers whirring.

And then into the final section of the film, a “what is really going on here?” discussion held by an assembly of students, who hash out the implications of the return of the statues and the wider resonances.

The cultural repatriation is part of a process of “decolonisation”, meaning not just a change in the ownership of a country when an imperial power moves out, but the cleansing of the culture of the lasting effects of the decades of rule by a foreign power.

Diop’s film gives us plenty of glimpses of the artefacts themselves, and gives voice to one of them, King Ghézo, with a magical-realism voiceover expressing in mystical terms his thoughts about returning home. But really her film is more interested in the young people and the discussion that takes up the last third of the running time.

The throne, the carved statues, the other treasures, which influenced the likes of Picasso (one glimpse of those big, bullish heads makes that clear), recede to a detail as these articulate, smart and good-looking students debate.

Passions run high. Nationalism is understood as a force for good. Contributors vie to outdo each other with condemnation. Scorn is poured on the French. One speaker warns about not throwing out the colonised baby with the coloniser bathwater. Another laments her inability to express herself in her own language and having to use French, the language of the oppressor.

Benin was itself a slave state, so some of the theorising of these idealists is on shaky ground, and the insistence on blood and soil as ultimate arbiters is the sort of ideological position that can be easily be repurposed – Blut und Boden, the Nazis called it.

It’s not entirely clear which way Diop herself leans. The score, by Wally Badarou and Dean Blunt, which has the jingle-jangle elegance of Isao Tomita’s synthesiser reworkings of Debussy, gives no clue either.

What’s admirable about her movie is that it captures the debate as it’s raging, its cool, well made points and its hot-headed extreme utterances. What’s undeniable, however, is that all this chat can get just a touch arid.

Cut to young African kids eyeballing their national treasures in the museum (a hotly contested word in itself) where they now reside. And the parents open mouthed as they stare. Some are fascinated, others spellbound, still others bored witless, and Diop shows them all.

So, after Atlantics, that’s the second feature-length film directed by Diop, whose uncle was Djibril Diop Mambéty, who made the classic Touki Bouki, and who’s clearly a big influence on his neice. Film-making smarts and an analytical cast of mind clearly run in the family.

Dahomey – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2025