Halfway through watching this simple but fascinating documentary, by the same team that made the equally eye-opening 97% Owned, a friend turned up. Instead of saying “How are you?” or “Wanna cup of tea?” (I’m writing this in the UK), I said, “God, I’m watching this amazing documentary about economics in Japan and how the authorities there deliberately sabotaged the country’s economy, and the whole 1980s boom and bust was a fix, and the…” and on I burbled.

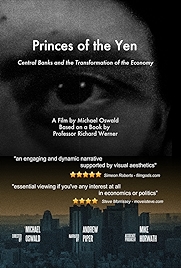

It’s not the reaction you’d expect to what is essentially a PowerPoint presentation, delivered in steady-as-she-goes voiceover. Yet the story the film (subtitle: Central Banks and the Transformation of the Economy) tells is remarkable, and is essential viewing if you’ve any interest at all in economics or politics.

And here’s the story it tells. The wrecked post-Second World War economy of Japan was restored to rude health not by the introduction of a free market economy (as the books tell us) but by the Bank of Japan (BoJ), which, using a system of “window guidance”, directed investment into whichever sector (or even company) that it saw fit.

Neo-classical economics dictates that a system like this will not, cannot, work. And yet Japan, with little in the way of natural resources and comparatively small in size, became the second largest economy in the world.

Part two of the story tells how, in the 1980s, this amazingly successful system was deliberately sabotaged for ideological reasons by people in the BoJ who believed that Japan needed “structural reform”, and that reform wouldn’t become politically or socially acceptable without a crisis. So, the BoJ engineered that crisis, first by jacking up the window guidance credit quotas, which led to a lot of excess money sloshing about, which led to the huge 1980s property boom. The documentary pauses here to remind us of some of those absurd factoids that were all over the media in the late 1980s – that the value of the gardens around the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was more than the entire state of California, for example. And then it continues, telling us that in 1990 the crisis came – the stock market dropped 30 per cent in one year alone, leading to a protracted economic freeze which Japan is still recovering from now. Between 1990 and 2003 real estate prices fell 84 per cent, the stock market by 80 per cent, 212,000 companies went to the wall.

Part three tells of the BoJ’s bogus attempts to restart the economy in the 1990s – it pumped money in on one side, then took it all out again on the other – all the while burbling about the need for “structural reform”, this of an economy it had itself destroyed. Then the neo-con Prime Minister Koizumi was elected in 2001 and there followed a period of even more “structural reform”, during which the bank balances of local banks were wiped out as they were bankrupted and forced into nationalisation.

Enough explanation of what the film says. Though I will just say that it goes on to detail how this disastrous formula was first exported to South East Asia, where it killed the Asian Tiger economies, and was then repeated in Europe, where from 2004 the European Central Bank sat back as “bank credit growth in Ireland, Greece, Portugal and Spain increased at over 20 per cent per annum.” And which were the countries that needed the bailouts?

I might be mistaken but I there appears to be very little, if any, new footage in this documentary. If that is the case, then Princes of the Yen is a triumph of archive remixology. That doesn’t mean there isn’t plenty of authoritative input, thanks largely to the wealth of TV interviews given over the years by economist Richard Werner, the coiner of the phrase “quantitative easing” whose book Princes of the Yen provides the film’s title and thesis. The cogent, amusing and bright-eyed Werner’s arguments could be boiled down as “this is madness”, or even “this is treason” (my interpretation of his sentiments) and I wished at times the film had been more explicit about what it seemed to be suggesting: that this “structural reform” brand of economics is US cultural imperialism by another name. And I wished it had either better incorporated its bigger argument – about the dangerous unaccountability of central banks – or even left it for another day. But for people like me, who are interested in economics but don’t have the vocabulary or conceptual framework to take part in the discussion, Princes of the Yen fills in some of the gaps, without bamboozling with jargon, graphs or too many statistics. And even if you are flatly, 100 per cent sure that every word the film says is wrong, the questions it asks, considering the economic hole we are currently climbing out of, are ones that need answering.

Princes of the Yen – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014