What is it about a film-maker who died around 25 years ago in obscurity that fascinates a new generation of directors?

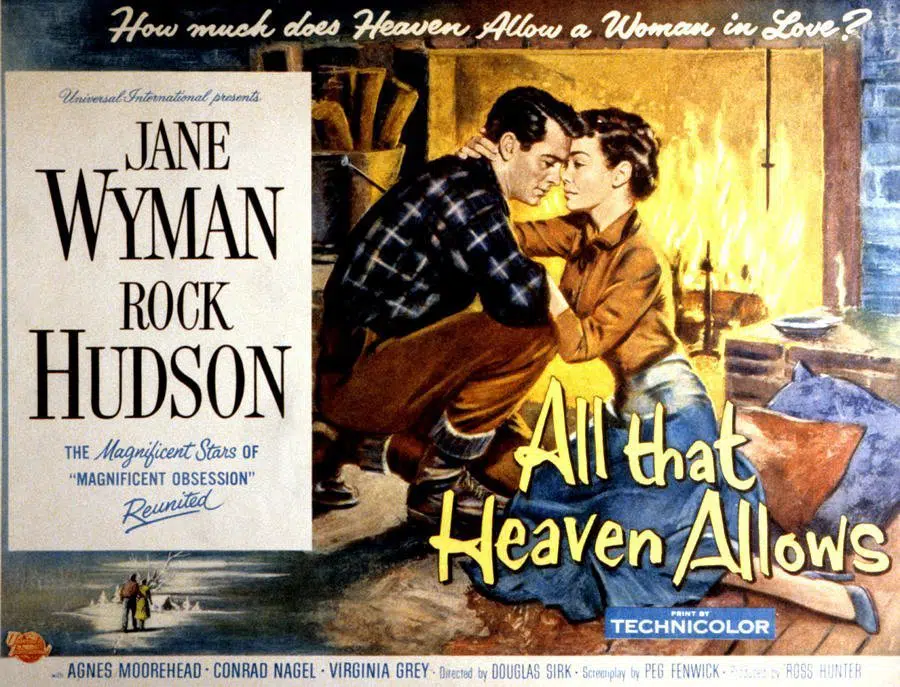

The director Douglas Sirk died in 1987 aged 90. Born in Hamburg as Detlef Sierck, he became well known for his string of lush melodramas made in Hollywood in the 1950s. Magnificent Obsession (1954), All That Heaven Allows (1955), Written on the Wind (1956), The Tarnished Angels (1957), A Time to Love and a Time to Die (1958) and Imitation of Life (1959) are considered his key works. The French “auteurists” were the first to start the re-assessment of Sirk in the late 1950s – the distinctive look of his films marking them out as obviously the work of one person’s hand. Since then his films, often originally dismissed as weepy slush, have been re-assessed as works of multiple meaning, ripe for ironic readings. Sirk, the theory now goes, was a much more nuanced film-maker than he was initially given credit for. But though critics were hot to re-appraise Sirk, film-makers (Fassbinder being a notable exception) were slow to follow suit – as genres went, melodrama was to be filed alongside the musical; neither of them were as sexy as horror, sci-fi or film noir.

But things have changed in recent years. Film-makers from Tarantino (in Pulp Fiction) to Wong Kar–wai (in In the Mood for Love) started referencing Sirk, and since then a new generation of directors, perhaps mindful that we were once again living in a conservative age, have drawn on his methods, his colour palette, his style of drama, to produce films unafraid to let it all hang out.

Joan Crawford never worked with Sirk. But my shorthand test for working out if a film is Sirkian is to ask myself – can I imagine Joan Crawford, stoically holding back the sobs, with the back of her hand to her forehead? If I can, then bingo, it’s Sirkian. Here are a run of modern films that all owe a debt to one of cinema’s great ironists.

Far From Heaven (2002, dir: Todd Haynes)

This is the film that announced that Sirk, hovering in the background, had moved back centre stage. A film about a lovely American family living the dream, it was photographed by Todd Haynes in the Tupperware colour palette Sirk would have recognised. Its theme – things are not always what they appear – couldn’t be more Sirkian either, as happily married Cathy and Frank (Julianne Moore and Dennis Quaid) start to acknowledge that their marriage isn’t all it should be after Cathy finds Frank kissing a man one day. She, in full headlong Joan Crawford flight, then starts to seek comfort from the gardener (Dennis Haysbert) while the husband is subjected to electroshock therapy in an attempt to cure him of homosexuality. Sirk would also have enjoyed that bit of medical intervention too – the primal and the thoroughly modern, that’s Sirk all the way.

Black Swan (2010, dir: Darren Aronofsky)

Aronofsky ditched his often rather monochrome, dialled down, cerebral style and kept the melodrama for his most Sirkian work – a camp furnace of a movie he keeps feeding with cinematic fuel till it’s white hot. I mean, rival ballerinas (Natalie Portman as a white swan trying to go dark; Mila Kunis as her nemesis), a controlling mother (Barbara Hershey), a draconian master of ballet (Vincent Cassel), a bitter former star (Winona Ryder, perfect), rivalry, bitchiness, vomiting, lesbianism, obsession. And again there an elemental, Sirkian thrust – by this gruesome process, Aronofsky says, girls are transformed into women. And by the film’s end Portman has indeed become the black swan, by sacrificing her humanity to become sexy, bending everything holy out of shape in the process. That last ballet finale, set to Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, is a seething dance of flying camerawork, rhythmic editing and increasingly gothic revelation. It’s pure Sirk, though he probably would have thrown in a bit more colour.

Blood Simple aka A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop (2009, dir: Zhang Yimou)

A remake of the Coen brothers’ first film is interesting any day of the week. That it’s remade by Zhang Yimou, the former cinematographer whose Red Sorghum, Red Lantern and House of Flying Daggers caused jaws to drop the world over makes it only moreso. Zhang relocates the story to feudal China, turning the characters into archetypes from Chinese opera – the older husband, the scheming wife, the fat buffoon, the cowardly lover – the Coens having already done most of the hard work. He then brings a Sirkian focus to telling the story visually. Always fanatical at getting things just so, Zhang has embraced digital technology to rework backgrounds, foregrounds, skies, anything he fancies. I don’t think there’s a sky in his Blood Simple that hasn’t been digitally messed with – dark, rain-filled clouds hover impossibly over sun-baked deserts. Sirk wasn’t really a man for comedy and this Blood Simple doesn’t fit thematically into an easy categorisation as nouveau Sirk, but the looks do, the use of visuals to do the work of pages of text, the way externals mirror internal states of mind, that’s all very Sirkian.

A Woman, a Gun and a Noodle Shop – at Amazon

Broken Embraces (2009, dir: Pedro Almodóvar)

Almodóvar’s film about a woman who has a great hold over men is largely a pastiche of Hitchcock but there’s a fair bit of Sirk in there too. It is melodramatic, deals with unbridled love, sacrifice, exotic illness, obsession, innocence and blindness (and all films that deal with blindness recall Sirk’s Magnificent Obsession). The twist-filled plot centres on Penélope Cruz, playing a whore who falls for a director. He then turns her – using all the gifts at his disposal – into a star. Has the metamorphosis exposed her true self? Or is there no amount of hair, make-up and transformative magic that can hide a person’s true nature. See The Skin I Live In for another of Almodóvar’s treatments of the theme, which also works at such a level of excess and with such a layering of irony that the phrase Sirkian also pops unbidden into the mind.

Flight (2012, dir: Robert Zemeckis)

The line where human weakness meets human grandeur is territory Douglas Sirk knew well. In Magnificent Obsession, a playboy disgusted with himself after inadvertently causing the death of a noble doctor decides to retrain as a doctor himself – to replace the man, or at least atone for the world’s loss. He falls for the man’s wife. He blinds the man’s wife. Now who could possibly save her sight? In Flight Denzel Washington, a drunk, cocaine-sniffing pilot becomes an accidental hero after saving a plane and most of the passengers on his flight with the sort of stunt-flying only he could pull off. Later, as accident inspectors poke into his private life he is called upon to decide whether to be noble or not. The nobility, the self-examination, the hand-wringing, that’s all Sirk. The lowering clouds reflecting the man’s inner torment (or murky morality, take your pick), that’s all Sirk too.

Love Exposure (2008, dir: Sion Sono)

There aren’t many film that combine soft porn, Christianity, kung fu and Japanese teen culture. But then Sion Sono is no ordinary film-maker. In Love Exposure, the first of his Hate Trilogy, he cues the opening credits one hour into a film that has up till then been soundtracked to Ravel’s Bolero. After them, the action shifts from the quiet boy who’s become the master of the upskirt shot to the young woman who, having cut off her father’s penis, becomes a coke dealer, a cult member and a dealer in bogus antiques. The third segment of this drama deals with a schoolgirl who makes money from smashing up houses. Extremism, indoctrination, cult beliefs, gang membership, obsession – be it with porn or exercise or religion – are what Sono is dealing in. And he serves the whole thing up as overcooked, over-plotted melodrama, Douglas Sirk goes quasi-anime in a world where even the schoolkids know what bukkake is.

The Box (2009, dir: Richard Kelly)

Richard Kelly famously made Donnie Darko, then the more troublesome Southland Tales. With The Box he returns vaguely to Twilight Zone territory with an adaptation of a story by Richard Matheson which put human flesh on the series of mind games called the Trolley Problem – you wouldn’t kill someone right in front of you, but what if killing them saved someone else? And what if the person you were killing wasn’t in front of you? Sort of thing. Here, it’s Cameron Diaz who is being tested, after a mysterious stranger offers her $1 million. All she has to do is press the button on The Box. The downside: someone, somewhere in the world, someone she doesn’t know, will die. Under the mumbo-jumbo wrapping what Kelly is presenting us with is an Adam and Eve story – Eve gains power and knowledge on behalf of humankind, but at what cost? It’s an elemental story, wrapped in the story of the disintegration of a suburban marriage, with a layering of paranoid melodrama, a keen interest in guilt, an even keener interest in the power of women. Sirkian, in other words.

The Burning Plain (2009, dir: Guillermo Arriaga)

Guillermo Arriaga wrote Amores Perros, which was a torrid affair with choppy chronology. The Burning Plain is similar, a whole host of intersecting stories unfolding over decades, all of them wildly emotional, held together by the most unlikely coincidence. It is essentially a Douglas Sirk film that’s been chopped up and re-arranged, a lot of small stories with a big melodrama at the centre of each – a plane crash, breast cancer, the rediscovery of a daughter etc. To go into the plot is spoilerish but there are three notable blondes in it – Kim Basinger, Jennifer Lawrence and, most impressive of all, Charlize Theron as a maitre d’ at a swish restaurant whose off-the-clock time is spent self-harming and having serial sex with strangers. Knotty.

The Hunt (2012, dir: Thomas Vinterberg)

Thomas Vinterberg famously made Festen, a drama about the nasty little secrets that lie behind seemingly blameless middle-class exteriors. In The Hunt he’s doing something similar, though he’s dressed it up this time in Sirkian self-flagellation, as we watch blameless teaching assistant Mads Mikkelsen being accused by a five-year-old of showing her his penis “sticking out like a rod”, as the subtitles put it. What then plays out is a The Crucible-like drama of hysteria in a small town, an examination of the way nice people actually make things worse by refusing to deal with the nut of a problem (there is an awful lot of euphemism in The Hunt) but most of all it’s the story of a lone man adrift on a roiling sea, continuing to proclaim his innocence to a world that has become deaf to him. That protestation of guilt, those judgemental eyes, that’s Sirk territory.

White Elephant (2013, dir: Pablo Trapero)

Pablo Trapero, one of the best directors working anywhere in the world at the moment, does love a bit of Sirkian angst. In White Elephant he tells us the story of a pair of priests working in an Argentinean shanty town which sits in the shadow of a never-finished hospital (the white elephant of the title). Set in the world of gangs, drugs and death, White Elephant splits its Sirkian business equally between the two priests – one (Ricard Darín) has a terminal illness he’s not telling anyone about. The other (Jérémie Renier), deeply traumatised after seeing an entire missionary village butchered, finds himself getting closer to the astonishingly beautiful volunteer in the shanty town (the astonishingly beautiful Martina Gusman), which is, of course, against his vow of chastity. The beautiful visuals are not Sirk (they’re more Scorsese) but the themes – secrets, temptation, redemption – definitely are. As is the way the drama builds slowly towards its conclusion, with Trapero holding back the melodrama right to the last minute.

A box set of some of Sirk’s best work – Buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2013