Steven Knight’s movie track record so far: when he only writes (Dirty Pretty Things, Eastern Promises) very good; when he also directs (Hummingbird), not so good. For his latest film, Locke, he directs, and the results are enough to make you forgive Hummingbird, the misguided attempt to inject soul into Jason Statham.

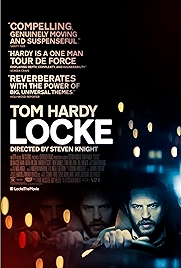

Because Locke is very very good indeed. And it’s so simple, a high-concept piece – perhaps what you’d expect from one of the brains behind the quiz format Who Wants to Be a Millionaire – which simply sticks a man in a car and has him drive and answer phone calls, drive and answer some more. One man, one car, some voices coming over the bluetooth hands-free, that’s it.

That man is an engineer – an expert in concrete slab bases – who has had an erotic dalliance a few months earlier. Now, as a result of that night of drunken passion, he’s about to become a father; the mother is down in London, crying, desperate and lonely. His wife, unawares, is at home about to watch the football with his sons. She’s cooking sausages and has bought in “that German beer you like”. Meanwhile, his underling back at the vast project he’s overseeing is wondering where the hell the boss has gone on the night before a crucial and huge “pour” of liquid concrete.

All this is established in the first few minutes. Over the next 90 minutes we watch Locke deal with all that – technical details to do with concrete, rebars and shuttering, the fallout from his absence at work, the increasingly desperate mother-to-be in the birthing unit, the wife and family at home – in what could very easily be a radio play.

If it were we’d be denied Tom Hardy’s performance as the softly spoken Welshman Ivan Locke, a man in a white shirt with graph-check pattern, pullover, untrendy beard, who has dedicated his life to the eminently practical – the concrete, in fact – partly, we learn, as a way of coping with the memory of his drunken, wastrel father.

If the father – whom Hardy addresses in angry soliloquy – and his backstory threaten to break the otherwise straight-ahead linear thrust of Knight’s urgent film, he’s the only real distraction, and Hardy’s subtle change of gear in these moments shows he appreciates this danger too.

It’s Hardy’s film, obviously, the emotions moving across his face like clouds scudding across the moon. But the voice talent lined up to punctuate Locke’s long night-drive of the soul are uniformly believable too. I particularly liked Olivia Colman as the needy Bethan, mother of Locke’s child, and Andrew Scott as Donal, the slightly feckless Irish concretist with a liking for cider.

Steven Knight spoke at the screening I was at. There were only about 40 of us and he had bothered coming out to say about half a minute’s worth, so he must be proud of the film. He told us it was an experiment shot back to back ten times in eight days (or was it the other way round?) – “then we edited the best bits together”. Thanks to the restless editing (by Justine Wright) and the cinematography (by Haris Zambarloukos), which turns the blurred motorway lights, passing cars and brightly reflective windscreen into a metaphor for Locke’s rushing mind, we’re as good as in the car with him. Is the mild mannered gent going to hold it together, or erupt? Is he, in his distraction, going to crash the car? Read on…

Locke – Watch it/buy it now at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2014