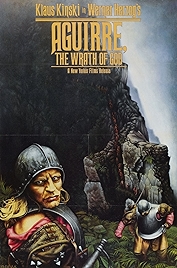

As madly vainglorious as the expedition it tracks, Aguirre, Wrath of God follows a raggle-taggle band of 16th-century conquistadors into uncharted South America, where they hope to find incalculable riches in the fabled city of El Dorado. It was the first of five uneasy collaborations director Werner Herzog and Klaus Kinski made together.

Herzog opens on a richly extravagant shot of the conquistadors, the accompanying nobles, plus native bearers and a priest in single file descending through the jungle down towards the Amazon. Money has been spent, the shot shouts. This is a magician’s deflection. Most of the “action” in this movie takes place either on a riverbank or on board a raft drifting down the river towards untold glory, or so everyone initially hopes.

Kinski plays Don Lope de Aguirre, the soldier with a demented gleam in his eye who leads a mutiny against his commanding officer when his senior suggests they should turn back. Aguirre knows riches have been found in Mexico and he wants more down here further south.

Up till now we’ve only had glimpses of Aguirre’s character, but once in charge he’s the zealot who will brook no compromise, determined to lead his men onward on a mission that takes on a messianic quality. And onward he does indeed lead them, into madness and death.

Talking about Apocalypse Now, Francis Ford Coppola once said, “Aguirre, with its incredible imagery, was a very strong influence. I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention it.” Would he ever. Never mind that Coppola’s Colonel Kurtz and Kinski’s Aguirre appear to be cut from the same fanatical cloth, Coppola also borrowed heavily from Herzog visually, from lens choices to mood to the use of nature. All those shots of Martin Sheen or Laurence Fishburne staring thoughtfully at the river while in voiceover a diarist supplies context (Sheen’s Captain Willard in Apocalypse Now – here it’s supposedly the priest, Brother Gaspar). All lifted from here.

There isn’t, see also Coppola’s jungle epic, much of a plot. Instead Herzog lets Kinski’s face do the talking. When it’s not big in the frame, boggle-eyed and calculating, it’s off to the side, twisted in a rictus, or shuffling into shot – Kinski’s Aguirre has a limp and may also have a hunchback. Shakespeare’s Richard III is clearly an influence.

This is the film that spawned a thousand stories, most of them about Kinski’s odd behaviour – like shooting a rifle into a tent because the sound of the crew playing cards meant he couldn’t sleep – but it’s also the source of the famous tale about Herzog pulling a gun on Kinski to make him stop behaving like a crazy man. It was Kinski who said a gun was pulled; Herzog claims he only threatened to kill Kinski, but no gun was pulled. Either way there was conflict.

Considering the stories that surround it, this is a remarkably quiet and contemplative film. Not much is said. When people die, they die silently. Animal hoots and tweets are often the only sound. Popol Vuh’s largely choral soundtrack (a mellotron, most probably) adds a churchlike atmosphere, as if the conquistadors are trespassing on sacred ground, or are heading towards some divine reckoning.

While it’s obviously a commentary on the sort of colonial adventuring lent moral justification and vocal support by Christianity, Herzog isn’t too naive. Aguirre may be madly bloodthirsty, but the natives he and his men encounter aren’t much better. They practise cannibalism – no noble savages here.

It’s remarkable top to bottom but watching it in the knowledge that it is made for next to nothing and Herzog is making it up as he goes along adds an extra degree of wonder. Herzog turns every misfortune, every lack, to his advantage. When the river rose and washed away his rafts, Herzog rewrote the script so the river rose and washed away Aguirre’s men’s rafts. He shot it in English (the only language everyone had in common), then dubbed it into German, which gives a distanced slightly documentary effect, as does the handheld camera, rare in historical films from this period. And the soldiers’ breastplates and helmets are all rusty, because they’re cheap props, but that rust tells a story – of cloying atmospherics and of an enterprise which, beneath the grand claims about the mission to civilise, is shoddy.

And yet, for all the haphazard, make-do-and-mend of Aguirre, it’s all exquisitely framed, beautifully shot… all of it on a single camera, stolen by Herzog from the Munich Film School. No wonder it is so mythologised.

Aguirre, Wrath of God – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023