In American Gigolo a man falls in love with the wrong woman and is framed for a murder he didn’t commit. It’s a classic film noir plot given a neo-noirish treatment in what looks like writer/director Paul Schrader’s homage to Howard Hawks and The Big Sleep.

The twist being that this is the 1980s. And how. Though released in the opening year of the decade, American Gigolo is fully immersed in it. Its hero is a male prostitute obsessed with consumerist stuff. He drives the right car, wears the right clothes (Armani), is coiffed to perfection, works out to keep his body gym-toned and his skin has that well hydrated look of a man familiar with the properties of retinol-A.

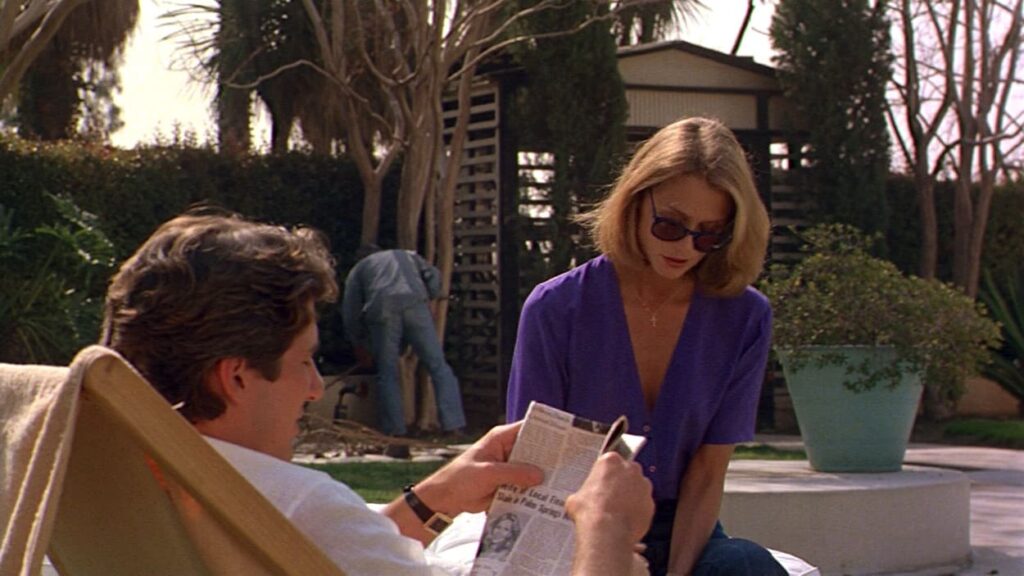

Julian (Richard Gere) sleeps with older women for money and works for a female pimp (Nina van Pallandt), but also turns occasional tricks off the books for a lower-rent operator, Leon (Bill Duke). It’s working on a “rough” job for Leon that lands Julian in trouble with the police, at roughly the same time as Julian is complicating his life further by falling for a woman he mistook for easy prey (Lauren Hutton).

The cultural critic Laura Mulvey’s essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, had introduced the concept of the male gaze five years earlier and, watching this movie again, it looks very much like one-time critic Schrader had read it. Not only does every woman in American Gigolo follow Julian appreciatively as he swishes through hotel lobbies and into expensive restaurants, but so does Schrader’s camera, lavishing attention on the male body even when there are naked female bodies to be appreciated. In the key lovemaking scene between Julian and Michelle (Hutton), it’s Gere who goes fully naked, not Hutton.

Julian might be gay, it’s suggested, though specifics are very hazy in this story, and plot isn’t really what it’s all about – see also The Big Sleep. Julian is the man who loves women – performatively at least – but who isn’t loved himself. In the end he winds up being framed for a crime he didn’t commit because, in the words of the person framing him, he’s so very “frameable”. Friendless. Soulless, perhaps. An existential antihero out of Camus.

For Richard Gere this film was the making and unmaking of his career. The character of Julian – moisturised, gelled, primped, tailored – is a feminised man, and therefore contemptible. Julian is regularly called “Julie” in this movie – it’s deliberate. This performance is what powered the rumour mill for decades afterwards: the gerbil stories (or was it a hamster?), the supposedly lavendar marriage to Cindy Crawford.

When Gere dies there will be a fulsome re-appraisal of his career – a lot of interesting films (I’m Not There, Arbitrage and Norman, to name but three) and plenty more riveting performances in films that were, themselves, sub par (The Flock, The Benefactor). And he’s been getting better with age. But until then he’s going to have to get by on a zillionth of the kudos other actors of his vintage get as if by right (like Jeff Bridges, born the same year).

He’s good in this film too, and if he suspects he’s boobytrapping his career he never lets on, lending a grace to proceedings that almost masks Schrader’s occasionally torpid pacing and his overuse of a noirish slatted shadow.

Years later Schrader would make The Walker, as a kind of sequel to American Gigolo – a check-in on what a man like Julian might be doing in the 21st century. It featured Lauren Bacall, an overt nod to The Big Sleep. It’s less overt here, doubly so with Giorgio Moroder’s synthy score reworking Blondie’s Call Me in increasingly gloomy arrangements as Julian’s life circles the drain.

There aren’t many laughs in American Gigolo. I don’t think there’s even one.

American Gigolo – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023