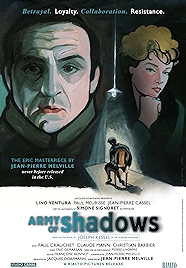

Jean-Pierre Melville is slightly off his turf in 1969’s Army of Shadows (aka L’Armée des Ombres). No trenchcoat-wearing criminals driving American cars. Instead he gives us a slice through the activities of the French Resistance during the Second World War. Like all his late-era film, from 1966’s Le Deuxième Souffle to 1972’s Un Flic, Army of Shadows is an absolute must-see.

Joseph Kessel, who wrote the original book, had been in the Resistance himself and based it on his own experiences. Melville, too, had been a member and is keen to present a nuts-and-bolts, warts-and-all portrait of the men and women who risked everything to help rid their country of the Nazi invader. The film is gritty, earnest and a long way from glamorous, though there is a steely resolve and stoic heroism at its centre that’s attractive.

Following Kessel, Melville gives us a sweep of what being in the Resistance means. Rather than an action-movie single story, a series of events, which link together only in the sense that they’re all part of the bigger picture of fighting a foe. Lino Ventura is the star, a ball of gristle and perfect casting as Philippe Gerbier, the boss of everyday operations, who we first meet on his way to a prisoner of war camp. In what’s almost a snapshot style, Gerbier is taken to be questioned by the Nazis, escapes, rejoins his comrades, then deals with a traitor in the ranks with a simple but grisly execution, is taken to London by submarine, returns to France by air, plots to save a captured colleague, and so on.

Melville holds the interest, particularly in the first part of the film, by making all these episodes little dramas in their own right – a new situation, a question posed, tension quickly set up, then resolved – before moving on to the next episode and repeating. In the second half, which moves Simone Signoret’s Mathilde, Gerbier’s number two, more into the mix, things become more longform and Melville allows a story to develop which will climax in the shocking death of a character we have come to know.

These include Luc Jardie (Paul Meurisse), the bookish academic who’s also the grand boss of the Resistance, Jean François Jardie (Jean-Pierre Cassel), who never realises that his own brother, Luc, is involved in the Resistance at all, and two shadowy characters known only as the Mask (Claude Mann) and the Bison (Christian Barbier).

Ventura and Melville had fallen out during the making of Le Deuxième Souffle and did not talk to each other at all during the making of this film. Instead they communicated through intermediaries. This seems petty in the extreme, but Melville was obviously big enough to realise that he needed Ventura to play Gerbier, and Ventura understood there was no one else like Melville, and that this role had his name on it. His playing of Gerbier is superb and in a film full of deadpan performances, his is the flattest, yet as expressive as a shrug.

Cinematography is by Pierre Lhomme, and, following Melville’s brief, he presents a drab world of blues and blacks, the colour desaturated, as befits a story about people who move in the shadows with little prospect of a taste of glory.

Arriving in the world in 1969, right after the events of Paris in 1968, the film got a hostile reception from the French critics. One brief scene in which General De Gaulle, head of the Free French in a London exile, pins medals on Luc Jardie and Gerbier was probably enough to sabotage it. A hero in the 1940s, De Gaulle was out of favour with anyone young or on the left by the 1960s. American distributors took their cue from the French critics and the film didn’t get a release in the US until it had been given a 2K restoration in 2005. Which explains why it appears on so many US “Best Of” lists in 2006, 37 years after it had been released.

This neglect meant that by the mid noughties, there was only one watchable print left in existence, and it had turned completely pink, according to original DP Pierre Lhomme, who supervised the restoration. It’s a thing of wonder, especially considering the state of the source material, with only one scene seeming a trifle pink and soft.

As with all Melville films the brutally realistic and the picturesquely cinematic rub along together, with Melville using lots of detail to bridge the gap between the two. And as with all Melville films at the centre of the story is a fierce belief in an almost chivalric code of behaviour from which and towards which everything flows. Death before dishonour.

Army of Shadows – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate