It’s remarkable that in film and TV adaptations of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair, it’s always called just that. Thackeray lifted the title for his satire from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, where a fair at a town called Vanity was an allegory for all the delights of the realm of the physical.

It’s hardly a punchy title, or one with any modern currency and yet it carries on being used. At least six movies and eight TV shows, not to mention various magazines, have used or are using its name. Apart from this 1935 adaptation, no one seems to have though to use the name of its principal character, Becky Sharp, instead. Not even the film starring Reese Witherspoon in 2004 or the mini series fronted by Olivia Cooke in 2018. Feminist times, you’d have thought, call for ballsy adaptations bearing the heroine’s name. Not so.

The reluctance partly stems from the fact that Becky isn’t much of a heroine, though director Rouben Mamoulian’s adaptation is on her side more than some. The story of a girl from the wrong side of the tracks fighting her way upwards through society using all the gifts at her disposal – guile and sex mostly – is an epic satire in Thackeray’s original 1848 novel, and was knocked into a manageable Broadway shape by Langdon Mitchell in his 1899 play. Here, Mitchell’s play has been reworked again by screenwriter Francis Faragoh into into 84 minutes of breathless, almost pantomime knockabout propelled by Mamoulian’s blisteringly fast and fluid direction.

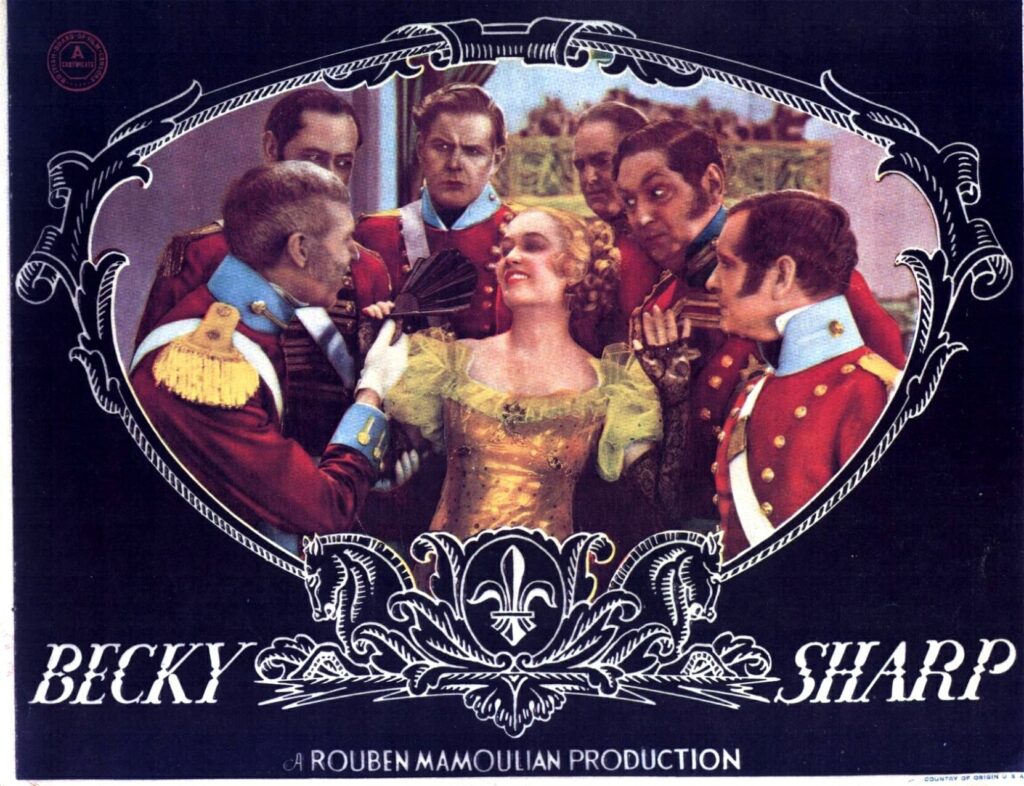

The film is also notable for being the first full-length three-strip Technicolor movie and in its curtain-up moment announces itself as such in a scene where the colours blue and red are prominent – two-strip Technicolor couldn’t really manage blue at all, and the three-strip improvement did red incredibly well. Mamoulian and the Technicolor technicians are deliberately wowing the audience with primary colours as they had never been seen on film before.

Three-strip renders red a bit too well in fact – never has the white man been more obviously the pink man – and Mamoulian takes his dramatic cue from the insane colour scheme, lavish costumes and deliberate juxtapositioning of hues for maximum Technicolor impact to deliver a movie that’s a pot pourri of almost nauseatingly bright scenes nailed together with almost indecent haste.

It’s the right approach and it helps obscure Becky’s shady motivation, to an extent, instead throwing the spotlight onto the array of British Empire Awfuls she is glad-handing her way through in an attempt to escape into the rarefied atmosphere of upper class society in Napoleonic England.

Miriam Hopkins plays Becky, who is meant to be maybe 15 when we meet her. Hopkins, at nearly 20 years older, is too old for the role and tends to wink to the audience in a “but that’s not what I really think” way. Graham Greene reviewed the film when it debuted and liked it, but wasn’t sure of Hopkins’s performance. In spite of Hopkins’s Oscar nomination for the role, Greene’s verdict seems like the right one.

In various other roles that look like they’ve been lifted off Toby jugs, it’s quite a cavalcade of performers playing the (mostly) men in Becky’s life. Nigel Bruce is particularly good as the bufferish, peuce-faced brother of Becky’s only real friend, Amelia (Frances Dee), while Cedric Hardwicke is also highly effective as the hideous old roué the Marquis of Steyne (pronounced “Stain”, appropriately) who’s desperate to bed Becky – but Becky is no fool. And Alan Mowbray is another middle-aged chap holding his stomach in, as Rawdon Crawley, a decent fellow and possibly Becky’s only real shot of personal happiness AND a swift elevation up the social scale.

Is Becky a bad person or just a poor girl using the only tools at her disposal? Becky Sharp leaves the verdict open right to the last scene, and even then it’s not entirely clear.

It’s a world better than the Witherspoon version from 2004, which simply doesn’t move fast enough, and a much better film than its reputation suggests. The colour schemes of clothes and set designs are sometimes glorious, sometimes off-putting, but the real reasons to watch are the right ones – good story, direction and performances.

If you are going to watch it, there is a good Kino 4K restoration (linked to below). It goes a bit fuzzy and pops a bit on what was probably the last reel but up till then it’s a marvel of restoration.

Becky Sharp – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate