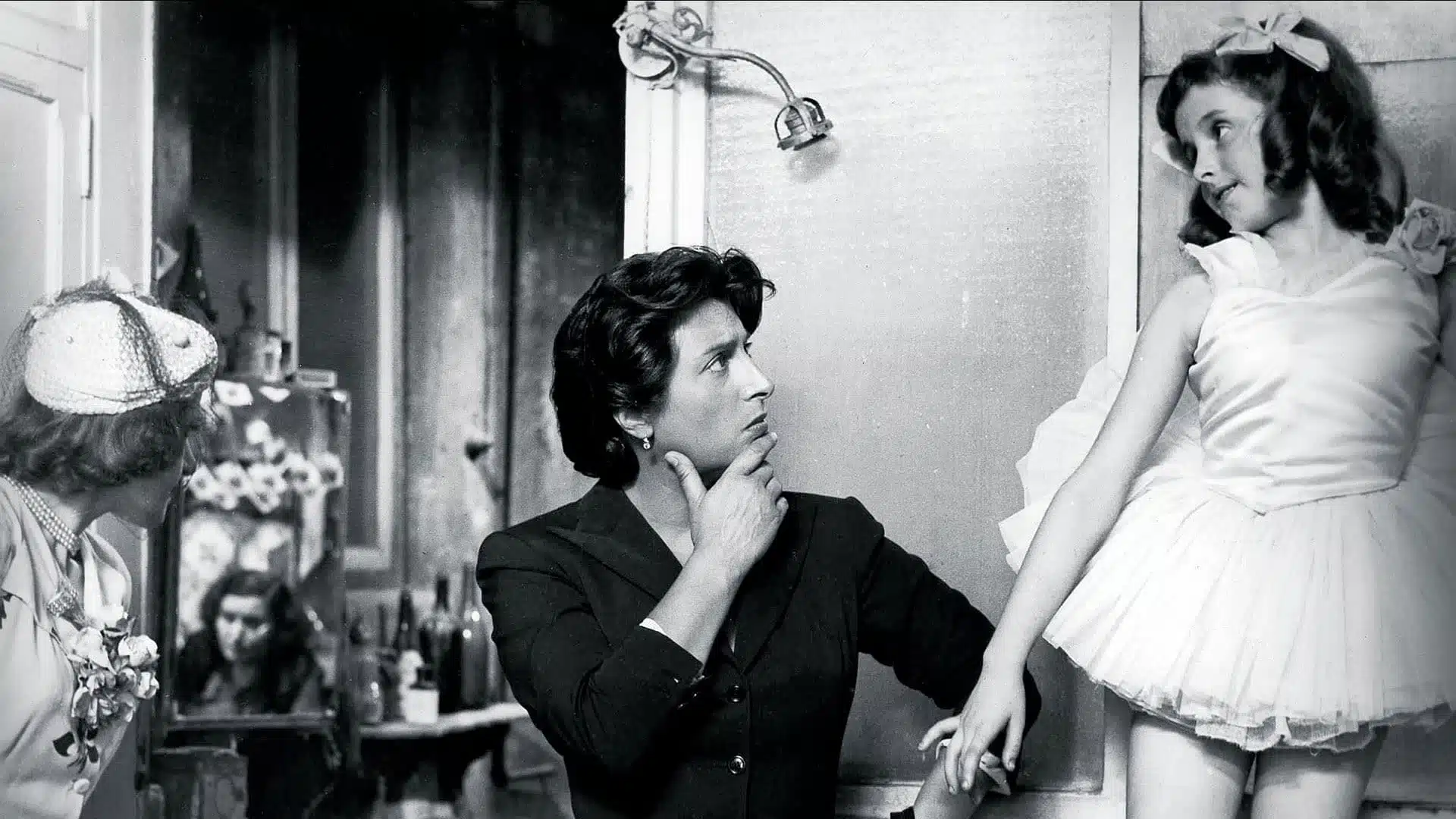

If it’s a performance you want – and I mean a performance – look no further than Luchino Visconti’s 1951 comedy Bellissima (Beautiful to English speakers), in which Anna Magnani turns on the acting flamethrower in the film’s opening moments and runs it at full intensity until fadeout.

She plays the mother with aspirations that her little girl shouldn’t live the same impoverished, largely hopeless, male-dominated life that she’s had – Maddalena (Magnani) strains every sinew in her body to get her girl into the movies. A casting call goes out on the radio in the film’s opening moments and from here we follow Maddalena and seven-year-old Maria (Tina Apicella) as they prepare for the upcoming screen test.

There are sketch-like encounters between Maddalena and the studio photographer. Maddalena and the dressmaker. The ballet teacher. Other stage mothers. The hairdresser. On it goes as the mother tries to get the daughter prepped and primped so that when Maria comes to do her party piece for the director and his posse she will be at her best.

The unspoken joke sustaining the whole thing is the daughter’s insignificance in all this. Maria seems a sweet enough girl but she’s not particularly talented, not particularly interested and she has a lisp. Visconti introduces her as an absence – her mother temporarily cannot find her disappeared daughter in the film’s opening moments – and what little story there is resolves itself in the film’s final moments when her mother spiritually finds Maria again, suddenly seeing her daughter as a little girl rather than a would-be actress and cash cow.

In between, stand back and admire Magnani at full spate, in a performance that’s a force-field of personality. Maddalena is the sort of woman looking for a stand-up row at every occasion and when she’s not charging barriers to progress, she is keeping up a monologue expressing her innermost thoughts. Maddalena is powerful, histrionic, clever, funny, coquettish, confrontational and sly, and deploys different character traits throughout depending on which way the wind is blowing.

Magnani never entirely acts to whoever is opposite her, even in almost-intimate moments with Walter Chiari, who plays a studio fixer hoping to get sex for favours from Maddalena. Magnani plays to Chiaria (and all her fellow actors) but largely she’s playing to the audience, a two-prong attack which is fascinating to watch. All actors do this to an extent, that’s what a performance is, but it’s the grandstanding way Magnani does it that’s impressive.

The film is often described as neorealist but it’s only nominally so. By 1951, when this debuted, neorealism had pretty much run its course. Visconti was one of its originators, theoretically in his work as a critic for Cinema magazine and practically with his debut movie, 1943’s Ossessione, the adaptation of The Postman Always Rings Twice announcing neorealism to the world.

Here he’s edging away from it, though trying to keep at least a superficial fealty to the genre he helped create. But the neorealist street settings, non-professional actors, documentary feel and lack of music eventually start to give way to something more recognisably Hollywood. The lighting on Magnani glams up around the halfway mark, a musical score creeps in, more and more scenes play out between people who are obviously professional actors.

It’s an intensely female-driven movie. Men control the household (Maddalena’s bullying husband, Spartaco, played in wife-beater get-up by Gastone Renzelli). They control the conduit between household and workplace (Chiari). And they control the workplace itself – the making of movies (director Alessandro Blasetti as himself).

But it’s the women who make everything work, and who fill Visconti’s picture – Maddalena’s neighbours, the clients she visits in the day job of vaccinating the wealthy, the fellow stage mothers, a domineering acting teacher (the funny Tecla Scarano, who isn’t in it much but gives Magnani a touch of her own hairdryer acting style).

The marvel of the movie, set often at Cinecittà, Italy’s home of dreams, and running on the high-octane hopes and expectations of Maddalena, is that it keeps a foot on the ground at all times. Partly it’s Magnani’s performance – there’s disappointment in there – but also Visconti and his co-writers’ neorealist apprenticeship.

Just before the film’s closing moments Maddalena meets Iris, a backroom girl at the studio who Maddalena recognises as having once starred in a movie. It doesn’t last, says Iris.

As a scene it doesn’t quite work, partly because Iris is played by Liliana Mancini, an elegant beauty, and having a job at Cinecittà of any sort is beyond the wildest dreams of most. But it is in a way this film in a nutshell – the gap between neorealism and Hollywood, the grounded and the aspirational being the fuel that makes this motor run.

Bellissima aka Beautiful – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2024