Three great abstract artists died in 1944, this revelatory German documentary from 2019 tells us. Two of them haunt the gift shops of the world’s museums of modern art: Piet Mondrian and Wassily Kandinsky. The third deserves to be in there with them, according to Beyond the Visible – Hilma af Klint (Jenseits des Sichtbaren – Hilma af Klint) – which goes on to make an even bigger claim. That this obscure artist working in relative isolation in Sweden was not just one of the greats but the very first abstract artist, and so one of the major figures in 20th century painting. Piet and Wassily need to budge up.

When MoMA’s Inventing Abstraction exhibition opened in New York in 2012, there no works by Hilma af Klint in this “definitive” overview of one of the major trends in 20th century art. When asked why this was, MoMA responded that they weren’t convinced that Klint “worked” as an abstract artist – raising the question as to whether MoMA is a museum of modern art or modern artists, as art critic Julia Voss, one of Klint’s numerous admirers, puts it succinctly.

Without explicitly answering the question – Halina Dyrschka’s documentary fights shy of negatives – some of the reasons why Klint became and remains so obscure are answered in the time-honoured way: talking heads, timelines and images. For starters Klint barely exhibited her abstracts. When she died in 1944, her will expressly anyone forbade access to her abstract work for 20 years. It languished under the roof in the home of her nephew, who dutifully carried out her wishes, where her paintings baked in summer, froze in winter. It’s a wonder, her nephew’s son, Johan af Klint says, that the work survived, given the temperatures.

But it did, the 1,500 paintings, the scores of sketches and notebooks, and they’re all in remarkably good shape.

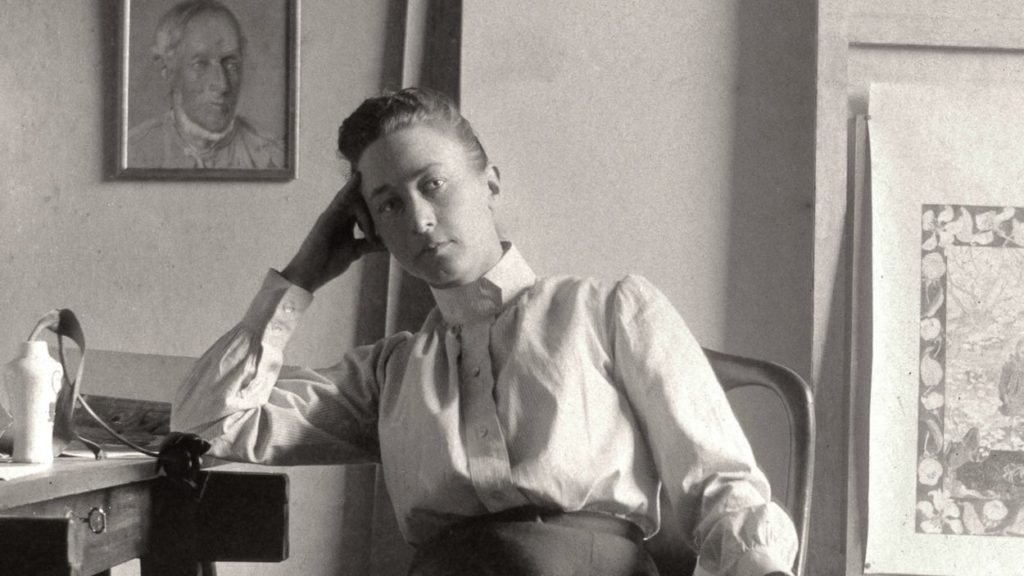

“Delicate” is how Ulla af Klint (widow of the nephew, recorded in 2001) describes Hilma, a clear-eyed woman in the photographs we see of her, who was born into an aristocratic naval family and encouraged by her father to pursue art. Her youthful sketches of poppies and cornflowers are beautiful, her exercises in perspective have a draughtsman’s correctness. She went on to earn a living as an illustrator, working in a naturalistic style.

Two forces drew her to the abstract. The early years of the 20th century were a hotbed of scientific discovery – the divisibility of the atom, radioactivity, quantum theory and of relativity. They were also a hotbed of spiritual exploration. Both sought answers to questions about the unknown, and in secret as early as 1906 the studious realist started working on abstracts inspired by both physics and theosophy. By 1911 Kandinsky had seen one of her works, “a historic painting”, he said.

The abstract works themselves come in all shapes and sizes, but the ones that make the most impact are large, bold, full of circles and spirals, blocky fields of colour, eye-catching and, yes, pretty, “delicate” even. At one point works by Klee, Twombly, Warhol, Kandinsky and Mondrian are juxtaposed with Klint’s. You can see all of them in her. Except she did it first.

It’s a boosterish film that would have been improved by a properly hostile counterweight – someone like the late art critic Brian Sewell at his most waspish – and at one point it dangerously veers off into a discussion about female artists generally being overlooked by the male art “club”. But the work either stands or falls on its own merits and in a film giving ample space to that work, nothing else need be said, surely.

Perhaps I’m being a bit male here. What I would have liked, though, is more of a discussion about the reasons for Hilma af Klint’s absence from the radar – she’s not even among the 100 artists or so, mostly but not exclusively male, on the MoMA Inventing Abstraction overview

https://www.moma.org/interactives/exhibitions/2012/inventingabstraction/?page=connections

and some on the list have very weak credentials.

Klint’s work was unboxed in the 1960s after the 20 year embargo and has been in circulation since the 1970s (the Swedish Museum of Modern Art were offered it all as a job lot in the 1970s and declined). Making a few untutored guesses, the fact that she didn’t entirely reject naturalism – as the men in the “club” did – probably didn’t stand her in good stead. The existence of works that mixed both the abstract and the natural (in my shorthand: they look 1970s album covers by Santana or Yes) was probably a double mark against her. Not serious enough. And her religiosity in an age of atheism probably didn’t help either. And there was the fact that she was a woman.

Beyond the Visible – Hilma af Klint – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021