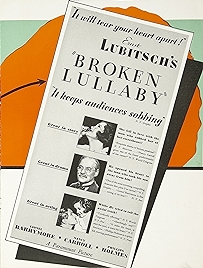

Ernst Lubitsch’s 1932 drama Broken Lullaby was originally called The Man I Killed, like the Maurice Rostand play it was based on (L’homme que j’ai tué). It turned out to be a title too hard-hitting for the box office and so it was decided to change it. To The Fifth Commandment. Until some bright spark pointed out that “Thou shalt not kill” isn’t always in the number five position in the Commandments. If you’re Jewish or Orthodox, it’s number six, for example.

And so, bizarrely, Broken Lullaby is what the movie ended up being called.

Both the play and the film are the story of a French soldier who kills a German soldier during the First World War. Stricken with remorse, and intending to beg for forgiveness, he heads to France when the war is over and connects up with the family of the dead man, in particular with his fiancée, at first witholding his true identity.

Irony is the big idea and Lubitsch lays it on visually in a brilliant opening sequence that includes images of marching soldiers, as seen through the legs of an amputee onlooker, as they parade past a hospital on the anniversary of Armistice Day. The watching crowds whoop and holler. A big sign says: Hospital. Silence! Inside, the noise from outside is causing shell-shocked patients/inmates to relive the horrors of war all over again.

It’s a film to watch for Lubitsch’s superb command of technique – the way his camera whooshes in and out on virtuoso crane shot, and side to side in fluid swoops that weren’t all that common in film-making of the early 1930s, unless your name was Fritz Lang.

It’s not a film to watch for the acting. Or rather it is, if what you like is overacting of a particularly ripe sort. Phillips Holmes has it worst. He plays Paul Renard, the French ex-soldier wracked with guilt (but not so wracked that he hasn’t noticed the dead man’s pretty fiancée).

Renard is a character who can’t see the difference between killing a man during peacetime and on active service during wartime, so perhaps Holmes reasoned that Renard must be mad. Holmes plays him as a man unhinged – Renards spends much of the film shouting, throwing himself to the ground in swoons, his face full of beseeching and imploring – from the moment we meet him at a church where a priest is trying and failing to console him, to the very final shot when… you can probably guess where it’s heading.

Everyone else, at various points, is hit by the same bug. Lionel Barrymore as the dead young German’s father has a particularly bad dose, and spends much of the film gurning and boggling his eyes. Nancy Carroll, as Elsa, the dead man’s pretty fiancée, has occasional bouts of it. Only Louise Carter, as Frau Holderlin, mother of the dead lad, escapes.

There are repeated examples of Lubitsch’s playful style – like when Renard and Elsa go for a walk through the town and all the shopkeepers come out to sneak a peek at the loathed Frenchman walking with the German girl who’s lost in grief, and the bells on their doors go ding… ding… ding… ding. We’re only four years into the sound era, but Lubitsch, who’d already made around 50 silent movies, shows he’s fully incorporated the extra possibilities sound opens up.

Lubitsch also moves the story on at a hell of a pace. The film is only one hour 15 minutes but everything is said that needs to be said in that time. When François Ozon remade Broken Lullaby – minus the histrionics and with the focus more on the fiancée – he brought the same story in at a (still tidy) one hour 53 minutes.

Frantz, Ozon’s remake, is a better film in almost every respect but Lubitsch has it beat when it comes to anti-war sentiment. In Barrymore’s big speech about the pointlessness of war and how xenophobic sentiment is kept alive by men “too old to fight but not too old to hate!” the film acquires a certain majesty, even if Herr Holderlin’s emotional volte-face seems a bit sudden.

Broken Lullaby was banned in Czechoslovakia, where its pacifist sentiments weren’t admired. It is one of the reasons these days for seeking it out. That and Lubitsch’s command of film-making. The acting – not so much.

Broken Lullaby – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate