Brother (Brat, in the original) is unusual because it’s not only a film made in the teeth of Russia’s economic collapse in the 1990s following the “shock treatment” prescribed by neoliberal economists from other countries, but it reflects the day-to-day reality of that treatment. Without anyone actually sharpening a political axe for the whole of its 96 minute running time, Aleksey Balabanov’s film nevertheless has a very clear point to make.

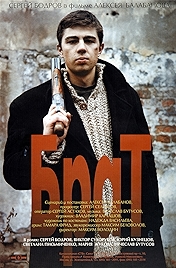

There’s a clear generational aspect, too, with the focus firmly on the younger inheritors of a broken Soviet system that’s now been broken even further by western intervention. In particular it’s on Danila (Sergey Bodrov), a drifter who’s just finished his conscripted stretch fighting the Chechen war, and winds up being arrested by the police after wandering uninvited onto a closed video shoot for the band Nautilus Pompilius.

Given little more than a talking-to by the police, on account of his military service, Danila is also given a talking-to by his mother, who suggests he goes to Leningrad (as she is still calling the newly renamed St Petersburg) to stay out of trouble with his older brother. Neither the cops nor the mother are aware that Danila is in fact a hitman for hire, and that once he gets to Petersburg it’s his brother who’ll need his help not vice versa.

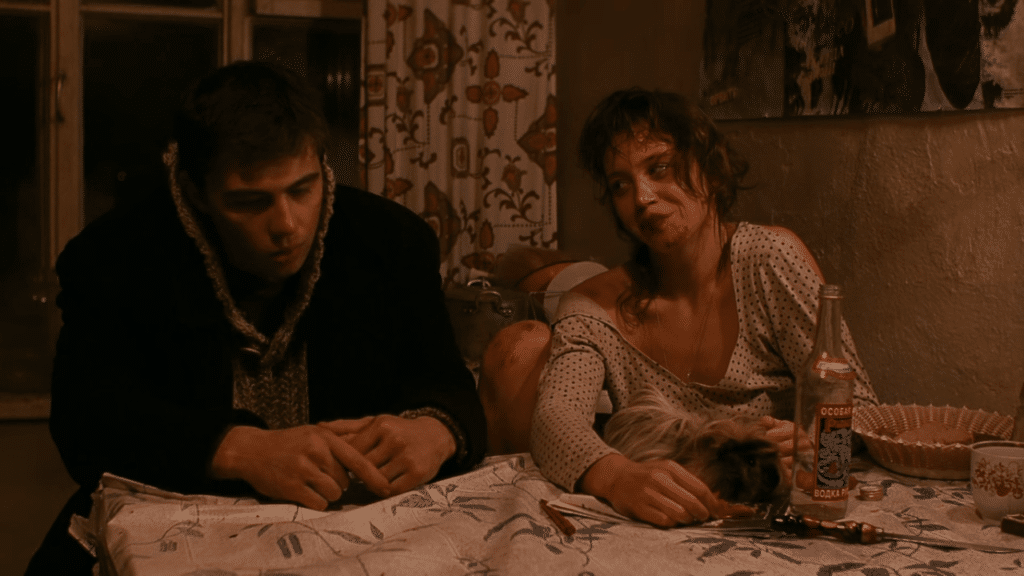

A familiar, almost Get Carter style story develops, with Danila as the man of few words sliding around in the Petersburg demi-monde, making friends and acquaintances from the edge-dwellers of a shattered economy – a street hustler called German, a tram driver called Sveta and Kat, a local punk with an extensive interest in drugs.

Meanwhile, Danila’s mission needs to be carried out – there’s a Chechen mafia boss to be wasted, but unbeknown to Danila he himself is also being followed by goons hired by the man who hired him.

Balabanov understands that a lot of this material is familiar and moves at pace. Scenes last no longer than they have to, the editing is brisk, and Sergey Bodrov’s performance as the taciturn and almost diffident Danila is of the charismatic/enigmatic sort. Surely a great international career would have been in prospect for the 25-year-old, if only he hadn’t died aged 30, in an avalanche in the Caucasus mountains. This film was enough to make him a star in his homeland, and spawned a sequel in 2000.

So, yes, the film was a huge success on its home turf. Some of that is down to its pace, some of it down to the star quality of its lead actor, the rest must surely be because, in an unshowy way, it is a state of the nation movie – shot entirely in a restricted range of browns, out on streets where it’s clear the infrastructure is falling apart and the people are scavenging to make ends meet.

Young people are the heroes of the movie. The older generation are too in hock to the old Soviet system, or the gangsterism it spawned. Only in scenes where Danila goes out clubbing with Kat for the night – though he’s having an affair with the older (and therefore “guilty”) Sveta – does anything like normal life intrude. They take drugs, they dance, for a moment they are free.

There’s a lot of ugliness in this film, not least in the way people die – in contorted shapes, legs jittering as life tries to cling on – a lot of vodka drinking, desperation, depredation and yet it’s not a depressing movie. Social networks – of kinship, crime, old political affiliations, of common human decency – are strong, as if humanity had been reduced to its basic building block. Not the individual – neoliberal economists take note – but the functional unit. It might be family, but it might be a group united in some common purpose, like a band – Nautilus Pompilius provide more than just the backing music to this downbeat but engaging and (if you’re not Russian) educational drama.

Brother – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022