Censor twists the horror movie into something it usually isn’t – a political satire. It’s set in the 1980s, when a media-confected moral panic about “video nasties” forced the UK government into regulating what had been until then the entirley unregulated market in home videos, kept supplied by thousands of tiny one-man (they usually were men) operations run out of corner shops up and down the country.

Until then the “board of film classification”, as it’s coyly known – an organisation funded by the industry and not by government – had dealt with theatrical releases only. There was barely anything else, after all. But as a result of the Video Recordings Act 1984, chased into law by British tabloid newspapers, all videos (and later DVDs etc) had to come with an age classification, and some films, the “nasties” – Driller Killer, I Spit on Your Grave, Cannibal Holocaust among them – were banned altogether.

The bill was introduced into parliament by Graham Bright MP, who later went on to try and ban acid house parties with a similar piece of legislation. So much for freedom-loving right-wingers. But I digress.

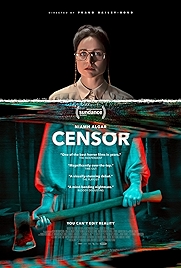

After a scratchy, glitching intro complete with 1980s-style production-house idents, we meet Enid and Sanderson, a pair of jobbing film censors, the sort who sit and watch films all day long and decide if it’s a yay or nay. Enid (Niamh Algar) is the “fastidious”, cautious one, aware of her duty to protect the public. Sanderson (Nicholas Burns) more laisser faire, is the one who references Shakespeare and Homer to justify his relaxed attitude to, say, a tug of war using someone’s intestines, or the excessive use of the screwdriver. They clearly have miles on the clock as co-workers. “It’s like Rat Brothel all over again,” he chides at one point, hoping to get Enid to loosen up a bit.

They’re either side of a debate that’ll need no fleshing out if you were alive in the UK in the 1980s. If you weren’t, writer/director Prano Bailey-Bond delivers a short, sharp montage sequence detailing the media hoo-hah aroudn the “video nasty” and the government’s eventual response. It ends with words lifted from a news report from the time – “There’s clear evidence that these films are lowering standards in society” – and then Bailey Bond retreats to let the story of Enid play out.

Things start to get interesting, because Enid, for all her cool and businesslike exterior, her cogently argued justifications for a “yes” or a “no” verdict, is a troubled woman. She’s never really recovered from the disappearance of her sister years before and is convinced she might still be alive somewhere. And then one day at work, she spots someone in a film who might bear a passing resemblance to her sister as she might look now, all grown up, and her fierce but tentative grip on reality starts to loosen.

Do horror films tend to “deprave and corrupt” (in the words of the Obscene Publications Act 1959) the people who watch them? In Censor they absolutely do, but then Censor is playing as much with the people who believe that sort of thing as with audiences who gobbled down Communion, Don’t Answer the Phone, Eaten Alive! and the like wholesale.

In a satire of biting precision, Enid goes mad in exactly the way that the legislation would have us believe happens to normal people, driven to mimic acts she’s seen on screen as day-to-day life and that of the films she watches for a living start to intermingle.

The Irish horror film The Canal (a worker at the National Film Archive finds life and art colliding) and Berberian Sound Studio (Toby Jones as a sound engineer having the same problem while working on a giallo horror) are obvious antecedents and Censor also operates like they do, building a convincing mood – this is a glum 1980s of greenish lighting, drab in the way many video nasties were, located in underlit offices, damp screening cinemas, underpasses, lonely bedsits. Until the screaming starts.

Niamh Algar must be in nearly every shot, certainly every scene, and in what’s mostly a series of close-ups of her face, she puts on a convincing performance as a woman who is under severe emotional torment but fighting to hold it all in. At one point, after a lot of deadpan turmoil, Enid half smiles and the effect is like fireworks going off.

Emilie Levienaise-Farrouch’s unsettling ambient soundscapes really help conjure dread and foreboding – it’s an outstanding score – and the cinematography of Annika Summerson reveals a DP entirely at home spoofing the lurid lighting of the cheapo horror of yore, when her moment comes.

Fans of Michael Smiley will enjoy his turn as an oily film producer with a Weinsteinian droit-de-seigneur attitude to any female he encounters, and Adrian Schiller plays Frederick North, a maverick director gone rogue up river. Actually, not up river, but out in the forest, though Bailey-Bond obviously has Kurtz in Apocalypse Now in mind. Well, it is all about the horror.

Censor – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021