Le Cercle Rouge, Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1970 gangster-heist movie, starts with a quote from the Buddha about all men eventually finding themselves inside the red circle. Regardless of what they think they’re up to, or how self-determined their actions are, human beings cannot outwit fate.

The quote is entirely bogus, having been written by Melville himself, who picks up and drops the idea of fate/luck/chance throughout his movie, relying on it to operate when he needs a fanciful meeting of two key characters to occur, for example, but keeping it out of the picture for the film’s centrepiece, a long, silent heist sequence.

The film is a self-assured and elegant exercise in style and technique, a homage to 1940s film noir – guys in trenchcoats, wearing hats, smoking, not saying much, driving American cars and frequenting the sort of clubs where young women sell cigarettes table to table – in much the same way that Chinatown also apes 1940s noir (which Robert Towne was sitting down to write when this first opened).

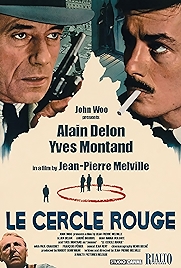

The plot: career criminal Corey (Alain Delon) gets out of prison eager to pull off a robbery, and accidentally winds up with Vogel (Gian Maria Volontè), a convict on the run, in the boot of his car. Together they recruit Jansen, an alcoholic technical genius (Yves Montand), to help them pull of a massive jewel heist. Meanwhile, a doughty cop – also in trenchcoat and hat – is doggedly pursuing the lone fugitive Vogel, little realising the jackpot this is going to yield.

The four leads are well cast. Delon is the ideal Melville actor – impassive, handsome, thoughtful-looking. Volontè sits well in the rough-diamond fugitive role initially destined for Jean-Paul Belmondo, a Melville regular. Montand actually does have the look of a man who’s just recently dried out, and André Bourvil is excellent as the fastidious and philosophical cop who embraces whatever leads chance might throw his way.

En route Melville examines codes of honour among men, as he tended to do. These loners (and the cop is one too) represent a peak of masculine agency. They act alone, only occasionally throwing their lot in with fellow lone wolves for the purposes of the job at hand. A gruff mutual respect develops. Friendship would be stretching it.

The long, beautifully restored version I watched, from Criterion, reinstates much of the footage cut in so many earlier versions. It now runs around 140 minutes, about 40 minutes longer than it used to, and gives us a lot more texture. At one point Corey guns his black Plymouth off the road, past an advertisement for Esso heating oil, and walks into a roadside eatery, all melamine, faux stone and chintzy muzak. Melville has an eye.

In a way Melville kept making the same film again and again – the guys, the coats, the cars, the love affair with America – and if you’re after a great example of late era Melville (he’d only make one more film before dying aged 55), Le Cercle Rouge is the writer/director in full flow. Go for 1956’s Bob le Flambeur if you’re after earlier, monochrome Melville (coats, hats, cars all also in evidence).

The 27-minute-long silent heist sequence towards the end is a clear echo of Jules Dassin’s 1955 classic heist movie Rififi, though Melville claims to have had the idea for a wordless heist before the American Dassin arrived in France in 1953. Either way it’s a marvel of how these things should be done, Melville a master of film geography – spatially, we know where everyone and everything is at all times – and it’s as good as the many, many reworkings of the Mission Impossible franchise or Ocean’s 11 – meticulous planning, lots of tech, tick-tock precision, men moving as if on castors, and communicating only with a nod.

Bechdel Test fans, look away, this is a film about men, and women feature only as waitresses, girlfriends or whores. There’s not even a femme fatale in sight.

Le Cercle Rouge – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021