The actor Antonia Campbell-Hughes is worth watching in anything she’s in. She’s particularly good at the externalisation of anxiety and there’s plenty of that in Cordelia, the story of a broken London woman trying to put her life back together after some terrible event.

The event was the terrorist bombings of London in July 2005, though all we learn of what happened then is how it’s left Cordelia, an actor now afraid to leave the house, who hasn’t used the Underground ever since (this was made in 2019 and is set then too), and who leans heavily on her twin sister (also played by AC-H), a boozy, fun-lover who is presumably everything Cordelia once was.

Over the hall a garrulous old man (Michael Gambon – on screen for maybe 15 seconds) who’s been laid low by age but is desperate to talk to anyone who happens by. Downstairs a mysterious cellist who practises all the hours.

Meanwhile, Cordelia is getting disturbing phone calls from a man who says he is watching her.

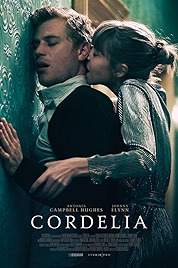

And then, one day, the cellist introduces himself to Cordelia, in a way that’s both over-familiar and too-respectful. A strange, possible, semi-romance of sorts gets underway, one that holds out the possibility that Cordelia will “get better”. Though that all depends on the true nature of the bumptious Frank (Johnny Flynn).

The phone Cordelia gets her disturbing calls on is an old bakelite number, 1940s possibly, and the décor in her place is also quite old fashioned. Director Adrian Shergold (who co-wrote the screenplay with Campbell-Hughes) bathes everything in shadows, tilting the visuals towards the crepuscular, and suggesting a psychological hinterland where the unseen has as much weight as the seen.

The 1940s psychological thriller is the idea, it seems, with Cordelia the modern update on the suffering Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight or the fearful Barbara Stanwyck in Sorry, Wrong Number.

Natalie Holt’s score adds in the febrile violins, screech-screech-screeching away, sometimes as a warning, sometimes as an announcement it’s too late for warnings. All part of a nicely conjured mood of pregnant threat.

At one point Frank encourages Cordelia to take a trip on the Tube with him – a mix of bluster and relentless supportive chat getting her down into the bowels of the earth where she hasn’t been since that fateful day – and on the way out you can spot a poster for Beast, the film that marked Flynn’s transition to to something more than a supporting player.

Deservedly so. He’s very good, making Frank a genuinely odd proposition – one part threat, one part idiot, one part loverboy. The early scenes together, between Cordelia and Frank, are like watching diplomats at work, each advancing their agenda while neither quite states what that might be.

Strangely, for all the brilliance of the set-up (and the payoff for that matter), something goes weirdly off in the climactic scene between Cordelia and Frank, when she suddenly recovers her mojo and reveals him for what he is. For a moment neither actor seems quite sure what their character is meant to be doing. Or was it their characters’ tentativeness I was confused by? I am not sure. Either way, the mood momentarily evaporated leaving behind exposed professionals at work rather than characters in a drama.

Campbell-Hughes remains beguilingly and creepily watchable throughout, those big saucer eyes, that impossibly slender frame as ever adding an extra dimension to so many roles where characters on the edge of society attempt to negotiate a re-entry. Cordelia is the latest and this was her first feature as a writer.

Since then she’s added directing to her CV and as I write It Is In Us All is bagging awards on the festival circuit (though the IMDb massive seem less enamoured, it must be said). Another film to add to the “must check that one out” list.

Cordelia – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023