It took Iranian exile Taghi Amirani more than ten years to make Coup 53, a documentary about the 1953 coup against the democratically elected prime minister of Iran, Mohammad Mosaddegh. The coup was organised and paid for by the US and UK governments. While the US long ago admitted that the CIA had a role in bringing Mosaddegh down, the ever-secretive British have never owned up.

At first it looks like that’s what Amirani is up to, getting the British to come clean. But as his film winds along, it becomes clear he has grander objectives. He unpicks the story of Mosaddegh’s downfall in detail – here’s how as a foreign agent you arrive in a country with a suitcase of cash and set about undermining a regime – and in doing so makes the point that the downfall of Mosaddegh soured the Iranian political well for generations to come.

With Mosaddegh still in charge, the regime of the repressive Shah of Iran would never have taken hold. And without the Shah there would have been no Ayatollahs, no hostage crisis in 1979, no concerns about nuclear weapons, oil sanctions and so on, right down to this day.

On a yet grander scale, though slightly harder to stand up, is the assertion that it was their success in Iran that gave the Americans the taste for regime change on a global scale, a taste that’s seen democratically elected governments in Chile, Guatemala, Congo, South Vietnam, Indonesia and Brazil toppled.

Journalist Stephen Kinzer sums it up succinctly towards the end – “When you read the history of the 20th century you’ll be lucky to read one line on this coup. It should be a whole chapter.”

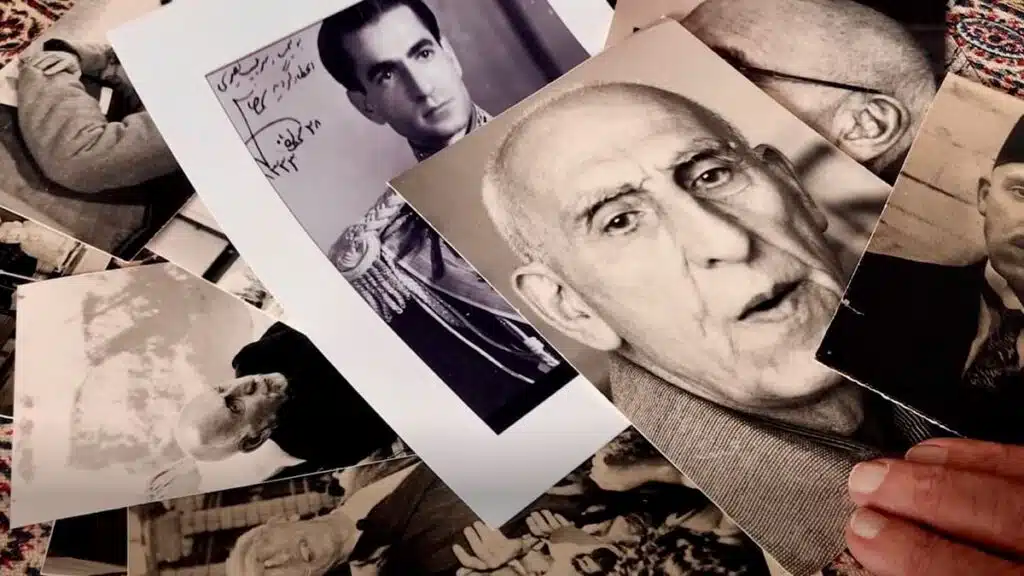

Amirani sets the scene well with extensive archive footage, depicting the colonial Brits in charge in Iran, where British workers for Anglo-Iranian Oil lived in splendour in Abadan and the British-government-owned company syphoned off huge amounts of wealth from the country. In 1951 Mosaddegh came to power and immediately nationalised the company. The Brits were expelled. But while Mosaddegh was being feted as Time magazine’s Man of the Year, wheels were being set in motion in London and Washington to topple the “left leaning” Mosaddegh (in fact a patrician who hated socialism).

The story is not enough. This is also a documentary in the Michael Moore, Nick Broomfield-style and so tells the “making of” story as well as the story itself, following Amirani into archives and into meetings as he puts together his final cut. This allows him to swing the great Walter Murch into the spotlight. The multi-Oscar-winning editor is a producer and edits both sound and image on Amirani’s slick and ultimately brilliantly coherent film. And it allows Amirani to introduce the shadowy character of Norman Darbyshire, the shady MI6 agent who did much of the work on the streets of Tehran and who told all to a mid-1980s 14-part British documentary series, End of Empire.

The story is not enough. This is also a documentary in the Michael Moore, Nick Broomfield-style and so tells the “making of” story as well as the story itself, following Amirani into archives and into meetings as he puts together his final cut. This allows him to swing the great Walter Murch into the spotlight. The multi-Oscar-winning editor is a producer and edits both sound and image on Amirani’s slick and ultimately brilliantly coherent film. And it allows Amirani to introduce the shadowy character of Norman Darbyshire, the shady MI6 agent who did much of the work on the streets of Tehran and who told all to a mid-1980s 14-part British documentary series, End of Empire.

The rushes for that series still exist, in the British Film Institute’s vaults. And the transcripts of all the various interviews still exist. But where’s the footage of Darbyshire? According to a preview of the TV show in the Observer newspaper in 1985, he was there on the screen. But come the actual transmission – gone. He’s been spookily expunged from the visual record.

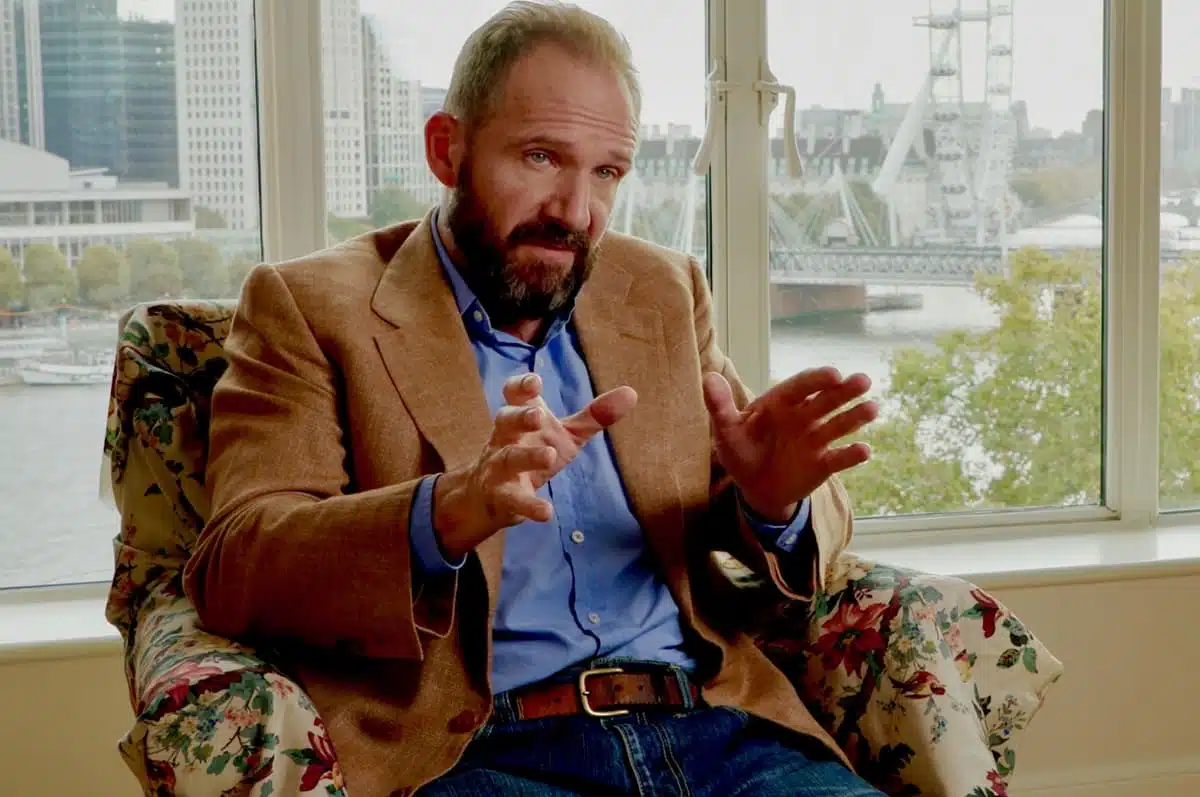

To get around the problem of a missing key witness, Amirani gets Ralph Fiennes in (Murch must have called in a favour – the two men worked together on The English Patient) to play Darbyshire, the voluble spy who when asked a simple question gave forthright simple answers and who, the suggestion is, only broke secret-agent omerta because he was miffed at the Americans getting credit for his work.

This is a stunt but it’s a good one, and Fiennes’s reading of Darbyshire’s words does not overshadow the testimony of those who were there, who are all old now (several died before the film saw light of day). As well as usual assorted exiled grandees, Amirani gets telling first-hand statements from the likes of Mousa Mehran, Mosaddegh’s bodyguard, as well as from one of the mob paid by Darbyshire to storm Mosaddegh’s house and remove him from power.

A mix of personal memoir, 20th-century history lesson, reminder of a world in which Britain was a major player and exposé on the shadowy world of spycraft, in its dying moments Amirani’s film also becomes an elegy to Mosaddegh himself, a highly intelligent, idiosyncratic (he met world leaders in his pyjamas) and cultured man who might have prevailed if he’d acted decisively at a crucial moment but instead lost out to external players and spent his declining years in jail and miserable internal exile.

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023