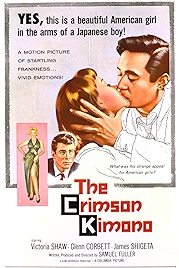

The posters are much more direct about what’s going on in The Crimson Kimono than the film itself is. Over a picture of a couple in a clinch they klaxon – “YES, this is a beautiful American girl in the arms of a Japanese boy!”. YES, this is a movie about a transracial relationship!

Columbia boss Harry Cohn wasn’t convinced that American audiences would be interested, or happy about, a story about such shenanigans but greenlit the film anyway, undoubtedly influenced by writer/director Sam Fuller’s ability to turn out profitable films quickly and cheaply – this was his second of three in 1959. Perhaps Cohn’s doubts also influenced Fuller’s decision to open his film as if it were a regular noirish crime thriller.

Opening shot: a sexy blonde is gyrating for the camera. She’s a stripper in some burlesque show. Seconds later the same blonde is running barely clad down a busy city street. Seconds after that she’s dead on the ground.

Whodunit, right? Enter two cops, a four-square handsome “American” (ie white guy), Detective Sergeant Charlie Bancroft (Glenn Corbett) and his buddy, Detective Joe Kojaku (James Shigeta), a Nisei (second-generation Japanese), a useful sidekick to have when the beat takes in the Little Tokyo area of LA.

The cops are intrigued by a painting of Sugar, the dead stripper, in a Japanese costume. She was working up a new routine, they’re told, one that included aspects of Japanese culture – a scene here about the cops visiting a dojo where bricks are smashed by fist power alone. Soon the guys have been directed to the painter of the portrait, a pretty young woman called Christine (Victoria Shaw).

And here, after what has been a lot of throat clearing, the picture gets going, becoming a knotty little threeway love tussle between two guys and one gal. The privileges of race and rank operate in Charlie’s favour. Joe, meanwhile, falls back on what might be called an Asiatic courtly decency though, in a key scene, he also demonstrates to Christine that he’s fully up to speed on all the dead white males. Joe knows his Mozarts and Da Vincis; Charlie is more your white-sliced sports jock.

From here it’s hot (and more than a touch predatory) Charlie versus nice Joe, with Charlie getting away first once the starter’s flag has dropped but Joe closing the gap once he realises he might have a chance with the slightly icy Christine.

With dead dancer Sugar having been almost entirely forgotten, the love plot takes over and eventually climaxes at a demonstration of kendo, where the two buddies take each other on and resentments romantic and racial spill over.

It is a culturally significant film rather than a dramatically urgent one. It’s obvious, once Fuller shows his hand, what he’s going to do. That was less the case in 1959, because the idea was so much more taboo, and the memory of all those American Japanese having been locked up in internment camps during the Second World War was still fresh.

In his typical issue-oriented way, Fuller addresses the “Americanness” of the Nisei. To his mind being American is about allegiance and nothing else. He sets one scene at a cemetery where there’s a monument to the Nisei who died in the Second World War, then follows up with a memorial to a fallen US soldier at a Buddhist temple.

It’s all done in Fuller’s no-nonsense tabloid-journalism style and he shoots it, as much as he can, out on the streets, where his DP Sam Leavitt (a regular Fuller collaborator, who also did Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and Cape Fear) gets to demonstrate his visual flair – sharp, high-constrast images as noirish as they come.

The music by Harry Sukman goes a bit oriental Hollywood plinky-plink cliché here and there, but it’s forgiveable. This is a story told in headlines, really, and it’s all summed up in the film’s very final scenes, when the real killer (it’s about a murder, remember?) is finally revealed and there’s a chase down a night-time city street, Sukman’s score metaphorically alternating – American, Japanese, American, Japanese – until it kind of no longer matters.

The Crimson Kimono – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023