1996’s Cuba Libre is only Christian Petzold’s second movie, after 1995’s debut, Pilots (Pilotinnen), but already he’s got the formula and the team all in place.

It’s a chilly thriller, in other words, with a man who’s losing his head over a woman, a woman who’s so otherworldly she might in fact be more metaphysical than real, and an overarching theme of escape, of existing in liminal space, of people perpetually on the way to somewhere else.

Petzold insists that all movies are in a sense about transit, or transition, but he’s got a very particular way of doing it. It’s the sense of yearning he imparts. It suffuses everything, to the point where it can almost start to be alienating, as it is here.

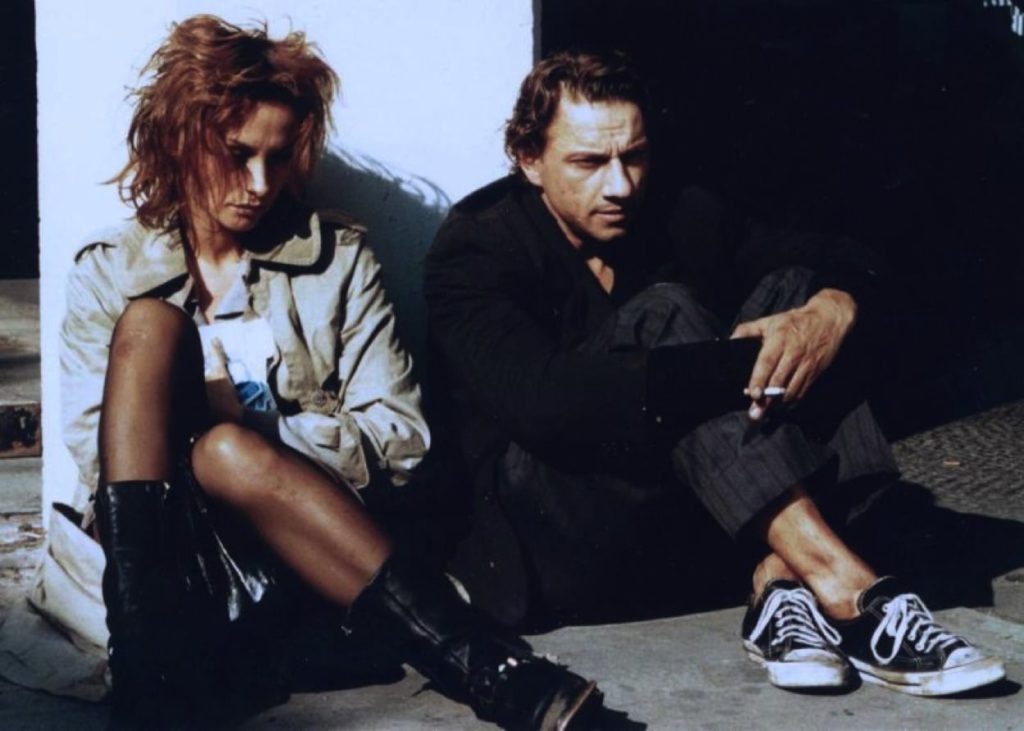

It’s a boy re-meets girl story. Whatever the glories or otherwise of their previous failed romance, the present existence of Tom (Richy Müller, the first of three collaborations with Petzold) and Tina (Catherine Flemming) is a grim one – she’s turning tricks for bored businessmen, he’s living in a hostel – but quite by chance they meet again. He’s keen; she’s not. Once bitten. But he’s smitten. And so a strange cat and mouse chase develops, after she takes hot-tails it out of Berlin and heads to Nice by hitchhiking, while he pursues her in the company of a wealthy benefactor with a dangerous heart condition who has appeared almost magically, acting as a kind of fairy godfather to Tom.

So it’s mostly a road movie taking place on the autobahns of Germany, exactly the sort of soulless, betwixt sort of place where Petzold likes to set his movies. She’s heading for somewhere, he’s in pursuit, though really he wants to go to Cuba, where he and she can start a new life together, with money from a safe deposit box, in a subplot so sketchy it’s obvious it isn’t really what Petzold is interested in.

The gang’s all here. Amazingly, they were mostly all there right on his first film, and Petzold has hung on to them ever since. Here, composer Stefan Will is the new arrival, drafted in alongside Harun Farocki (co-writer, script editor, co-conceptualiser on most Petzold films until he died in 2014), and DP Hans Fromm, who has lensed all of Petzold’s best films (Yella, Barbara, Phoenix, though it’s a tough call). In the years to come Will is going to become an absolute fixture, like the others, and here contributes a cold, repetitive incidental music to match the cold lighting, the drab locations and acting that’s deliberately disengaged, particularly in the case of Flemming.

She’s the Petzold heroine, and like later iterations – like Nina Hoss and Paula Beer – is a cool, slender and enigmatic beauty who plays up the mythic aspects of her character. Nina might not be real. She might be a figment of Tom’s imagination. She might be a figment of her own.

Yeh, it’s a bit arthouse. There are no heroes. Everyone is damaged goods – Tom and Nina most obviously, but also the side characters, like Jimmy the fairy godfather, and Pendler (“Commuter”), the guy buying sex from working girls and giving each of them the same spiel about being a bored husband with a dull family life, when in fact he’s just an asshole.

Cool to the point of detachment, after Pilots, which was a clearing of the throat, this marks Petzold’s arrival as a man with something to say and an idea about how to say it. He’d do it better in later films, perhaps having realised that drama is the glue that keeps people watching while you’re telling them what you’ve got to say.

There are more gripping films, in other words, though don’t let that put you off. Really.

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022