Let’s just get this out of the way. Daisy Kenyon isn’t a film noir, even though it features on many noir “best of” lists. It’s a romantic melodrama of a very peculiar sort – “High powered melodrama surefire for the femme market” is how Variety described it on its release in 1947, in their odd, truncated way of communicating. More up-to-the-minute viewpoints can be found on Amazon – “NOT a true example of film noir”… “certainly not a film noir”… “DEFINITELY NOT FILM NOIR” – three of many. However, the tagging persists. It’s in the Fox Film Noir series of movies, its Amazon page pegs it as “Mystery & Suspense/Film Noir”, which is doubly, if not triply, wrong.

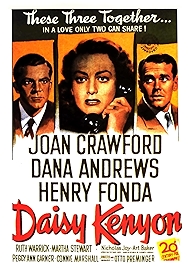

Perhaps it’s the knottiness of the plot that has thrown people (though not, it must be said, people who have watched it). Joan Crawford, in another of her post-Mildred Pierce woman-fighting-adversity roles, plays Daisy, an urbane magazine illustrator having an affair with entitled lawyer Dan (Dana Andrews), and hoping he’ll leave his wife for her, though that seems unlikely. Into her life comes Peter, hot back from the Second World War and a decent sort who falls for Daisy with almost reckless haste – he’s got a touch of PTSD and so is a touch unstable.

Daisy loves Dan, Dan says he loves Daisy, Peter also loves Daisy, though that might not be everything it appears to be. As the story plays out, Peter proposes to Daisy, Dan’s wife sues for divorce and the proverbial hits the fan in a number of ways. A love-triangle melodrama was unusual material for Hollywood at the time, and writer David Hertz attempts to make his adaptation of Elizabeth Janeway’s novel more acceptable by playing down the sex. There’s none whatsoever. Instead it’s replaced by the sort of clenched emoting that was Crawford’s specialty.

This is a great role for Dana Andrews, as a heel who doesn’t see why he can’t have it all, a bad guy who never sees himself as anything but a white knight. Entitlement doesn’t begin to cover it. What Dan – a kind of oily Cary Grant smarm on the go the whole time – most needs is a punch in the face. Henry Fonda, by contrast, is in another of his Noble Fonda roles – the guy who has put it on the line for his country (actually, Europe, but let’s not go there just now) and is now back home again, where he finds that Dan and his ilk have been cleaning up (money, women, whatever’s going) in the interim. The character of Fonda’s Peter turns out, in fact, in a neat plot twist, to be what Daisy Kenyon is about.

It’s a story about the intersection of personal and a larger morality, told at speed by Otto Preminger, who is here warming up his later oeuvre – socially engaged melodrama – and hoping that Crawford, Andrews and Fonda will give him a hit after a patchy run since his Hollywood breakthrough with 1944’s Laura. Daisy Kenyon failed to connect with audiences at the time. Maybe releasing it on Christmas Day wasn’t the best idea.

However, the years have been kinder, at least partly because this is a prime example of exquisite Hollywood craft – Leon Shamroy’s cinematography is non-stop superb. His lighting is exquisite, even though the “beauty lighting” he’s put on Crawford is laughably obvious, an attempt to knock ten years off the age of a 42-year-old woman going through the menopause (Crawford kept breaking into sweats and had the studio cooled to 50ºF/10ºC). Crawford, for her part, puts on a display of girlishness that’s actually rather touching.

For Hollywood it’s an oddly grown-up and unsentimental movie, though the censor apparently got more exercised about the amount of alcohol being drunk – count the martinis! – than the suggestions of extra-marital sex.

I watched the Kino Lorber Kino Classics DVD, which is sharp, rich and rewarding, especially if you’re into monochrome lighting in the high Hollywood era and the whole film-as-craft experience.

Daisy Kenyon – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022