So this is what “the most watched TV movie in US history” looks like – The Day After, a disaster-movie-style treatment of nuclear apocalypse from 1983. “Most watched” is one of those tags up for debate, obviously – watched on the day of transmission versus watched again and again, for example. Or watched in the olden time of big broadcasters and mass viewing versus the Netflix era, where everything is a TV movie one way or another.

Less up for debate is how effective Nicholas Meyer’s film still is. And it’s become increasingly relevant all over again as Russia pushes its armies into eastern Europe, while in America a debate rages over whether the US should be involved in this fight at all or leave the Europeans to it.

The same debate rears its head temporarily in The Day After too, which is entirely quiet on the counter argument (which ran like this in the Cold War era: if the US is going to get involved in a nuclear war with the USSR, let’s stage it in Europe, not at home).

Anyway, to the film, which sets out its stall just like a disaster movie – introducing just-ordinary folks and then subjecting them to hideous catastrophe. As the lights come up, tensions are high out in Eastern Europe, where the USSR has forces massed along the Fulda Gap – the bit of Germany where East meets West (and which, incidentally, Napoleon also used to advance into Russian, and reverse out again). It looks like they are about to pull aside the Iron Curtain and invade West Germany.

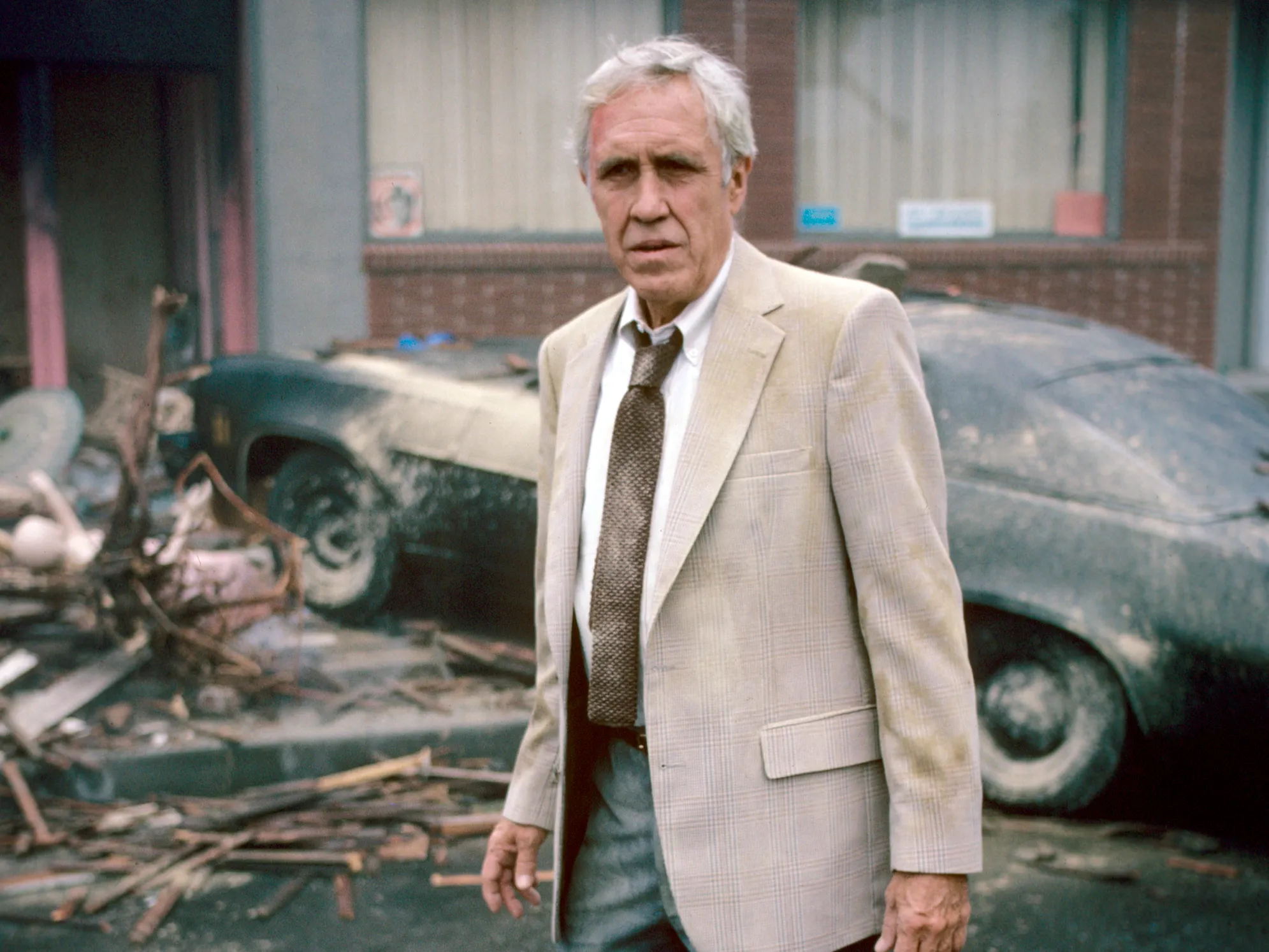

We meet Dr Russell Oakes (Jason Robards), a dignified avuncular doctor of high standing. Jim Dahlberg (John Cullum) and clan, gearing up for the wedding of their daughter. Dennis Hendry (Clayton Day) and his family on their farm. Pre-med student Stephen Klein (Steve Guttenberg one year before Police Academy sent his career into orbit). Joe Huxley (John Lithgow), a guy in a barber’s shop who reckons he knows better than most. And Airman Billy McCoy (William Allen Young), one of an army detail guarding ICBMs in silos tucked away in rural Missouri.

Everyone is nervous about developments, and Meyer builds the tension brilliantly – switchbacking between preparations by the US military for a nuclear war (handheld, documentary style) and the concerns of the everyday Americans we’ve already met (shot in a warmer, more conventional style).

Meyer deliberately builds a folksy image of the sort of America that’s under threat in his montage-style opening credits – of farms and small towns, mostly. A city flashes up in his montage but it’s a fairly small one. There’s a factory production line at one point, but it’s also pretty gimcrack and relatively bijou. It’s an image of a country on a human scale, a simple, honest country that doesn’t deserve to fry.

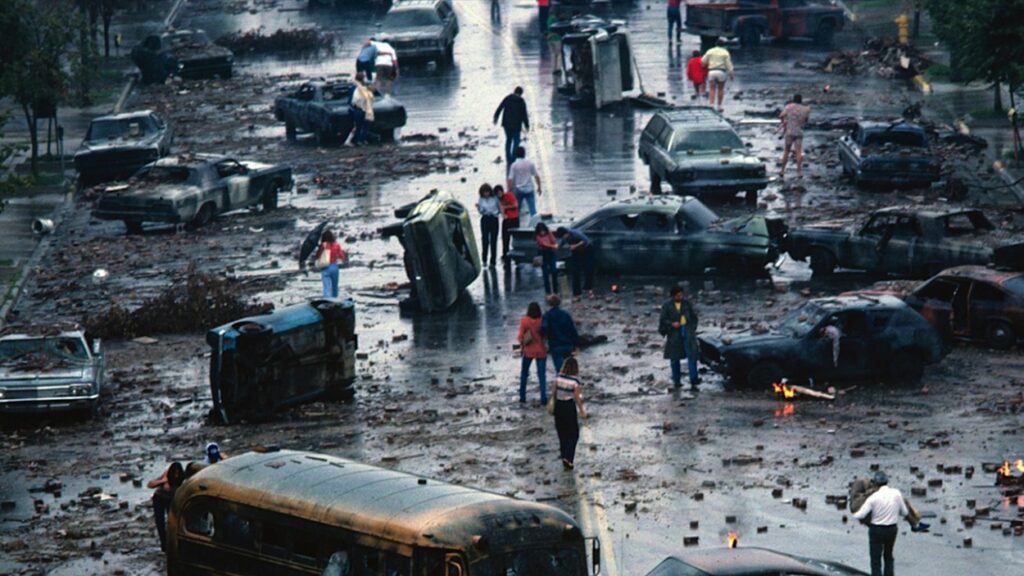

Meyer’s film divides up neatly into three chunks – the build-up, the short, sharp catastrophe and the aftermath, an apocalyptic vision of total societal collapse, where anarchy and lawlessness are the order of the day and a cohort of survivors scrabble for survival, disfigured by radiation sickness. It’s all very well handled, even the nuclear explosions themselves, which are done with chromakey effects and despite the vintage tech convey the awesome destructive capability of a massive attack.

Even better are the make-up effects and are doubtless what shocked a lot of viewers. It’s worth remembering that US TV at this time was dominated by Dallas, Dynasty and The A-Team.

Kansas City comes in for a bit of a pounding. A lot of a pounding, in fact, and ends up looking like Hiroshima. Dr Oakes doesn’t come out of it much better. Caught in the blast while heading down the freeway trying to escape, he selflessly tends to the sick at the university hospital where he works until, hair all falling out, he succumbs to radiation sickness and heads out into the devastated outdoors, joking wanly that he’s going to take some leave and that it’s a good time of year for a vacation.

Robards is the moral centre of the film, the guy who wouldn’t wish this apocalypse even on an enemy, and the film drew criticism in some quarters for not making it clear who launched missiles first. (“Why is Nicholas Meyer doing Yuri Andropov’s job for him” said the New York Post). Which, of course, is deliberate – Meyer’s concern is nuclear weapons, no matter who is using them.

In this regard it draws some inspiration from the British film The War Game, so plausible that it won the Oscar in 1967 for best documentary feature (the fact that it isn’t a documentary seems to have passed everyone by) which was also keen to point up the destructive power of the new weapons rather than make political points about “guilty” and “innocent” parties, when the upshot of a nuclear war on this scale renders such arguments facile. Nowadays the criticism is more likely to be that it’s very male and very white.

Watch it, it’s chilling and highly effective. Thanks to smart marketing – by anti-nuclear campaigners, not the ABC network – it got that “most watched” record back in 1983, by building a buzz long before the show aired. Whether it really changed President Reagan’s mind about his approach to the USSR is moot, but it must have had some impression (Reagan watched it several times). It’s smart alec Joe Huxley who sums it all up, at one point saying, “You know what Einstein said about World War Three? He said he didn’t know how they were gonna fight World War Three, but he knew how they would fight World War Four: with sticks and stones.”

The Animal Kingdom – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2024