The title of Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1966 gangster drama Le Deuxième Souffle is often translated as The Second Wind, though The Last Gasp would also work pretty well, since it’s a story about a career criminal breaking out of jail and trying to get out of France with his woman. Stuck for cash, the fugitive takes part in a “one last job” heist, which does indeed turn out to be his one last job.

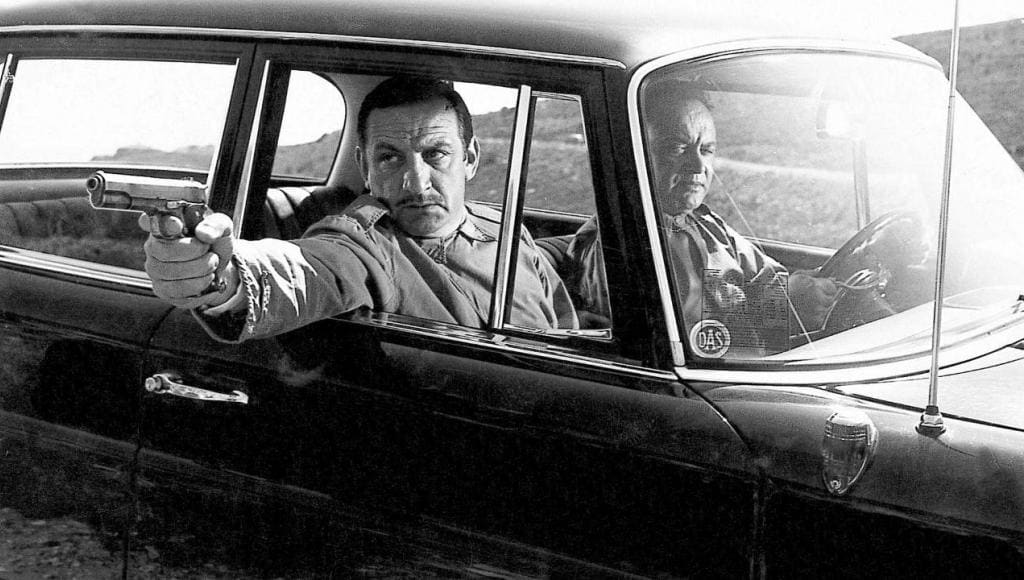

Lino Ventura plays the criminal Gu, short for Gustave, so ruthless a character that Melville puts up a disclaimer before the film that he personally does not condone any of the actions that the audience are about to see on screen – it’s just a story, he’s saying, more or less. It’s great casting, Ventura being a former wrestler and exactly the sort of man’s man that Melville liked to use in his films, the better to explore codes of masculinity, and particularly of criminals.

If that first paragraph is a bit spoilerish, in my defence I’ll just point out that there is a doomed aspect to Gu from the start. That’s perhaps the film’s greatest attribute, its atmosphere of fated inevitability. Gu, far from a good guy but in some way an existential hero Jean Paul Sartre would recognise, is determined to live his life according to his own lights, and if that means death, then so be it.

Opposite Gu, and the only character who really has full use of their face – Melville keeps the rest of them under rictus-tight control, a smile rendered as a flick of the corner of the mouth, anger as a tiny flash of the eyes – is Commissaire Blot (Paul Meurisse), the cop on the case and an avenging angel who’s charming, suave, a bit of a ladies man, clever and hugely sarcastic. When Blot arrives at the scene of a shooting early on, he goes from one “I saw nothing” witness to the next, not even bothering to question them, and instead telling them the story they’re about to tell him, detailing exactly how they saw nothing.

Melville was known for his love of American movies and this is a 1960s movie with the ambience of a 1940s American one – hats and macs, cars and bars, and a femme fatale (in the shape of Christine Fabréga) with only a totemic function. Manouche (Fabréga) has little to contribute to the plot but is there because… well, that’s the way these things are done.

Detail is the other thing that Melville is famous for and his command of a fetching location. Le Deuxième Souffle is screengrabbable in the extreme. Especially when it gets to the moment of the grand heist, when tightly claustrophobic interiors suddenly give way to the wide open expanse of a windy, hairpinny road where a bullion van containing platinum is about to be jumped by Gu and his new brothers in crime.

Atmospheric, impeccably filmed in rich monochrome (this was Melville’s last black and white film) and beautifully edited, this film is a delight for lovers of craft and technique. But it’s also a long, slow film and, considering that its plot can be sketched in half a sentence, can be a frustrating watch if you’re not in the mood to bask in the locations Melville has so painstakingly chosen – a swish nightclub, a grotty hideaway, a lush apartment where Paul Ricci (Raymond Pellegrin) is organising the heist Gu will eventually join, the heist panorama itself – and the tightly controlled actors Melville has chosen to play his characters. Was any film better cast? Every face tells a story, from that of Fabréga, the blonde floozy, to Marcel Bozzuffi, who plays mastermind Paul Ricci’s crooked brother, to Michel Constantin, a noble henchman with a doomed thing for Manouche.

There is honour among thieves in Le Deuxième Souffle… until there isn’t. Melville’s story isn’t really about criminal justice catching up with Gu, but about the criminal code of honour failing him when it matters, and in Lino Ventura he has an actor who wears the realisation that his time might be up on his face from the first frame.

Le Deuxième Souffle – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021