Ryûsuke Hamaguchi delivered two chunky movies in 2021. The three hour Drive My Car followed hot on the heels of Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy. Both movies are interested in identity and the way humans sometimes make use of lies in order to access truth.

It’s a case of the theatre director, his driver, his wife and her lover, with the slightly hangdog Hidetoshi Nishijima playing Yûsuke, the grieving actor-turned-director trying to put on a production of Uncle Vanya with a cast using his celebrated avant-garde methods – different people talking in different languages (including one actor using Korean sign language).

It’s a metaphor for the gulf between speech and meaning – language as metaphor – but Hamaguchi spices up the potentially indigestible with a subplot involving Masaki Okada, who plays the hot young actor who was tupping Yûsuke’s wife just before she died. Yûsuke knows he was. But Koji (Okada) doesn’t know that he knows and isn’t aware that Yûsuke has hired him to be in Uncle Vanya for reasons that might have nothing to do with the play.

Yûsuke continues the pretence that this is a straightforward director/actor relationship, just one element of subterfuge in a story that is ripe with examples of misunderstanding, lies, missing information and deliberately withheld facts.

This all takes place after a long preamble – the opening credits come up at about 40 minutes in – during which we’ve gained an insight into the life Yûsuke had with his very sexually driven wife (Reika Kirishima), a woman who has risen high in the world of TV by turning her sexual fantasies into sellable screen drama.

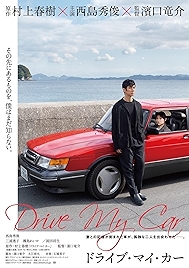

Humans are slippery in Drive My Car. The one thing that isn’t is… Yûsuke’s car, a red Saab 900 Turbo that is his pride and joy. He is driven to a rehearsal space in it every day by his driver, Misaki (Tôko Miura). And as he travels, Yûsuke listens to a tape of Uncle Vanya which his wife recorded before she died to help him learn the role when he was acting in it. Uncle Vanya’s bits are missing – he’s meant to fill in those bits.

There are lots of missing bits in this film. But, as said, not the car, and not the driver. It does what it’s meant to do, and she also. Unambiguously. No gap between intent and delivery. Significantly, humans in cars often – because eye to eye contact is less of a requirement – say things that they find difficult to say in other situations.

It is the car that allows Yûsuke to come to some sort of accomodation with the past, to process his grief meaningfully and to edge towards some level of engagement with the people around him – his actors and collaborators.

If it sounds tough going, it is. This notion of lies as truth and truth as lies pervades every aspect of the drama, to the point where you might feel like saying “OK, I get it,” but there are compensations to be had, not least from the strange slow-cooker relationship between Yûsuke and Misaki, whose thousand-mile stare makes her an almost impenetrable character, until she announces something more momentous than anything else that’s happened in the film. A fact, not an opinion, a bald statement of truth in a landscape of shifting meaning.

Fans of Uncle Vanya and its lives-soaked-in-ennui storyline can find some thematic read-across, but search high and low and you’ll not find any connection to the Beatles (Haruki Murakami, who wrote the original short story, likes his Beatles titles – Norwegian Wood is another).

In one hour less Hamaguchi told three times as many stories in Wheel of Fortune and Fantasy, a film that did with a scalpel what this does with a hammer. The suspicion lingers that Hamaguchi has overreached by taking Murakami’s original 40-page short story and blowing it up to a three-hour drama. In the process cudgelling Murakami to death.

Drive My Car – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate