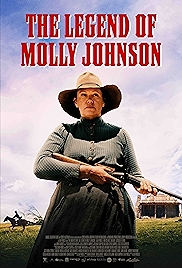

Leah Russell stars, writes, directs, produces and plunders her own family history for The Drover’s Wife (aka The Drover’s Wife: The Legend of Molly Johnson), a fine-looking revisionist western set in the Australian Outback.

Russell plays Molly, it almost goes without saying to say, a woman left to fend for herself and her kids out in the back of beyond while her husband is away droving sheep up in the high country. Handy with a gun but with a tendency to shoot when the red mists descend, Molly may be suffering from a form of PTSD, as no one back then ever called it.

It’s writer/director Russell’s first fictional feature (she’s done some documentary work) and she paints a John Wayne-esque portrait of life in 19th-century Australia – rough and ready, raucous and lawless, fights breaking out for no reason, people getting shot, men’s men throwing their weight about, a racial hierarchy firmly in place. Russell and her DP Mark Wareham shoot it all in epic widescreen, and at pin-sharp resolution, the juxtaposition of lone female against wide open unforgiving spaces clearly influenced by Russell Drysdale’s stark 1945 painting, The Drover’s Wife.

Drysdale claimed his painting wasn’t based on Henry Lawson’s short story of the same name. Whether it was or wasn’t is immaterial, since Russell took that story about a lone woman and her four children dealing with a snake that’s crawled under the homestead and infused it with elements of her own family history, inflating it, first into a 2019 novel and then into this screen adaptation.

No snake. Instead a series of encounters, all potentially perilous. First Sergeant Nate Klintoff (Sam Reid) and wife (Jessica De Gouw), en route to the local town where they hope to bring civilisation to this godforsaken corner of the world. Then Yadaka (Rob Collins), an escaped Aborigine who turns out to be quite the male role model once he’s been freed from his manacles. A later cop (Benedict Hardie), with a gun and in no mood for being to be told to go away. Two belligerent drovers wondering where Molly’s husband is. In town meanwhile, the local busybody (Maggie Dence) is scheming to have Molly’s children removed from her, on the grounds that they might not be white through and through. “Ocatroons” isn’t a word you hear much in movies these days. Leah Purcell, having Aboriginal ancestry herself, is probably familiar with it.

It is a good story and it’s well told, though eventually a traffic jam of sorts develops as the various plot elements head toward their individual moments of resoluton, and Molly and the kids, Molly and her husband, Molly and Yadaka, Molly and the law, and Molly and her husband’s drover pals line up to be dealt with in a last third where storylines stack up like planes circling a busy airport.

Add Molly and the racist patriarchy to that list too, in a finale where the implicit is made explicit in unnecessary conversations between Molly and the lawman’s wife. There’s a good half an hour too much material in this film, and it’s nearly all at the back end.

Up to that back end this has been an impressive movie, with moments of exquisite beauty and an evocative soundtrack of fiddles, banjos and gentle electric guitar (by Salliana Seven Campbell) capable of suddenly flipping us from the bucolic and folksy to the urgent and dangerous without much change of instrumentation.

Rob Collins is particularly good as Yadaka, and the relationship between him and Molly is the emotional heart of the film. But so is Russell the actor – impassive and impressive in time-honoured John Wayne/Clint Eastwood style – as Russell the writer/director tells her story. It’s heartfelt, sometimes overly so, but then she does literally have skin in this game.

The Drover’s Wife: the Legend of Molly Johnson – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate