Whether you call this long and detailed documentary Ennio: The Glance of Music or Ennio: The Maestro, or just plain old Ennio – all three titles seem to be out there – one thing remains constant. It’s a love letter to one of the most famous film composers who ever lived.

It’s directed by Giussepe Tornatore, a master of the billet doux – see Cinema Paradiso – and he brings a picturesque film-maker’s eye to bear on his subject. There’s lovely lighting, a breezy narrative structure and rhythmic editing, and Tornatore carefully montages together the standard-issue clips and reminiscence elements to lift this documentary onto another level. It’s a labour of love.

It’s also really helped by the quality of the talking heads. Unlike a lot of this sort of thing, they actually have something to say. Admittedly they’re quite often repeating each other but the same story retold by the likes of Wong Kar-Wai, or Bernardo Bertolucci, Dario Argento, Lina Wertmüller, Barry Levinson or Oliver Stone mints it anew. That story goes like this. Director X wants to use a different piece of music in his/her film than Morricone imagined, maybe even – absolute heresy – something written by somone else. The ordinarily timid Morricone tells them that if they do use it, he’ll walk. They cave, he wins, and they now admit he was right.

There are others singing their praises, like Bruce Springsteen, Metallica’s James Hetfield, the Clash’s Paul Simonon, Joan Baez, Quincy Jones and John Williams, which gives an idea of Morricone’s reach. They’re largely in “we’re not worthy” stances. Most interesting of all, because they know Morricone best, are the figures from the Italian music scene, whether it’s Alessandro Alessandroni (who played guitar and provided the whistling for A Fistful of Dollars) or Boris Porena, a fellow conservatory student with Morricone who speaks at length about how Morricone’s willingness to experiment ostracised him from the serious music establishment, until they had to grudgingly admit he was actually better than any of them. Porena, who has died since, while warm in his praise, looks as if he’s still inwardly struggling with the conceptual change of gear Morricone forced him to make all those decades before.

Morricone’s story is interesting too, being the rare one of the kid who wanted to have a professional career (a doctor) but who was forced into a life in music by his father. Playing the trumpet had allowed Morricone Sr to provide for his family all these years, so his reasoning went, so it would be good enough for Morricone Jr too.

From here Morricone starts living the sort of dual life he’d pretty much spend the rest of his life living, with one foot in the world of popular music, the other in the academy. Studying at the conservatory under Goffredo Petrassi by day while playing the trumpet in dance halls and music halls by night. This led to work on films, as a trumpeter (he’s on Orson Welles’s Othello), before Morricone moved on to doing “slave” work as an arranger for TV, then into pop music, where, several interviewees suggest, he was the first musician to provide arrangements for Italian pop stars, rather than mere accompaniments.

His love of Stravinsky and John Cage, and another sideline as part of the experimental Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, led him to start introducing unusual noises into his arrangements – tin cans, typewriters, tubs filled with water.

He was prodigiously productive. One old pop star from the early 1960s talks of Morricone knocking out an arrangement to a song while taking a phone call.

From pop music to TV to the movies, and his first film score in 1964, for The Fascist. More exactly, this was the first film score with his own name on it. He’d done two westerns in 1963 under an assumed name, to stop the disapproving Petrassi finding out what he was up to.

It’s around here that Sergio Leone called. Both of them were shocked when they realised they’d known each at school. Contact re-established, they saddled up for A Fistful of Dollars, Morricone coming at the score from all sides. From the avant garde John Cage direction, the anvil, the bell, the whip and whistle. From popular music, the electric guitar. From the academy, the swelling strings and celestial choirs.

Film music history was rewritten and a star was born. Between this point and his death in 2020, Morricone wrote music for films good, bad and ugly (to mangle a title), among them Battle of Algiers for Gillo Pontecorvo, The Arabian Nights for Pier Paolo Pasolini, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage for Dario Argento, The Mission for Roland Joffe and The Untouchables for Brian de Palma. In 2007 he won an honorary Oscar, aged 79, in what the Academy clearly intended to be a “thank you and goodnight” award, but Morricone kept on working, winning a “proper” Oscar for Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight in 2015.

All this, the figures from popular and academic music, the old friends, the directors singing his praises, the fantastic music, the intensely researched clips (you’ll be making notes to check out loads of films), the archival photo stuff, brilliant though it all is, and easily enough to furnish a decent documentary on its own, pales when compared to the commentary provided by Morricone himself.

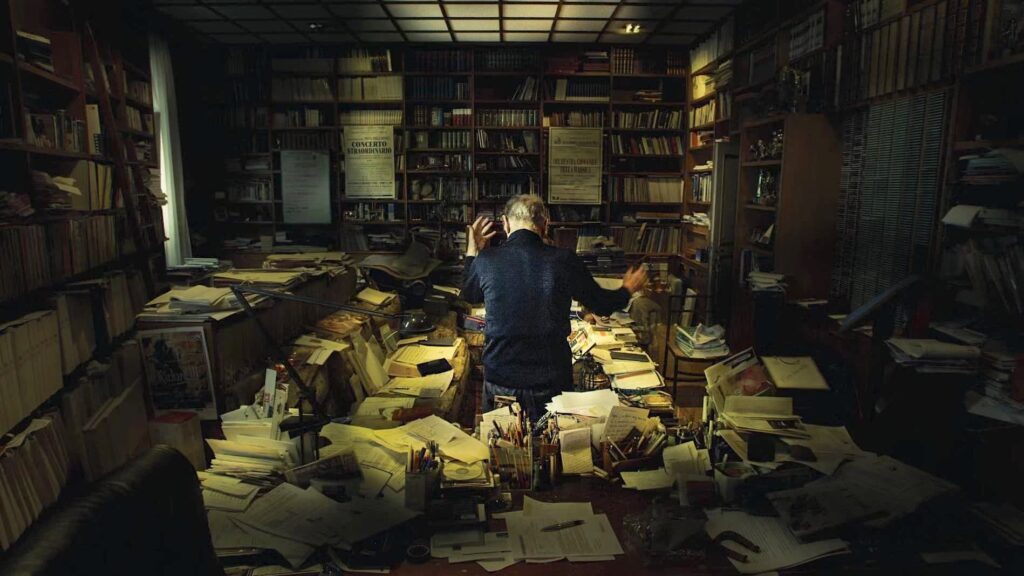

Interviewed extensively in his apartment – and first glimpsed grunting his way through his morning Pilates – he is a brilliantly engaging, open and frank interviewee, who remembers it all and is happy to talk about all of it as if he’s never spoken about it before. Better, he puts a musician’s stamp on the whole endeavour (and Tornatore must be praised for going in hard at the level of music, when he could have sailed through on celebrity name-dropping and fun stories alone).

As he talks, it’s obvious Morricone is back in the moment in question, stopping to illustrate what he’s talking about by humming or singing a theme – he obviously has perfect pitch because he’s hitting all the notes at exactly the pitch they should be at (confirmed by overdubbed extracts of the score in question – they’d never autotune The Maestro, surely?)

Little reveals add spice. How he wouldn’t use his father as a trumpeter because dad had lost his edge and the son couldn’t tell him. To get round it he told his dad he just wasn’t using trumpets at all. And for a long time he didn’t. He laughs, with half a tear in his eye, at the memory. How he hated the music for A Fistful of Dollars, the key work in his film-score career. How he’s a composer with a low regard for a melody (“He’s lying,” one contributor retorts). And the role of his wife in it all – “Directors only heard the music my wife liked.”

Both Hans Zimmer and John Williams marvel at how recognisable Morricone’s music is, often from the first note, and Zimmer in particular looks baffled and awed at how he’s doing it.

The last 20 minutes of this satisfyingly hefty (156 mins) documentary are essentially a standing ovation to a composer who vowed in 1961 that he was going to give up the movies in 1970. Finally, nearly 60 years later, a fracture took him off, with more than 500 screen credits to his name. Surely no movie composer has been more productive. And so much of it is great, great music.

Ennio – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate