Fanny and Alexander won four Academy Awards at the Oscars in 1984 and was the first foreign movie to have done so. No foreign movie has ever won more and Ingmar Bergman’s film has only been matched twice in the years since – by Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Parasite (2019). At the time it was the most expensive film ever to come out of Sweden and was designed by Bergman to be his last, a grand autobiographical flourish to explain the man behind a remarkable run of astonishing movies as the director started to look back at his accomplishments.

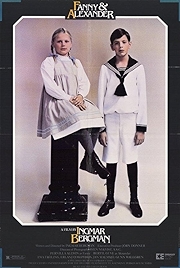

With that autobiographical aspect in mind, and armed with the knowledge that Bergman’s films tend towards a certain austere, protestant severity, welcome to the most lavishly dressed sets you’re ever likely to see (that’s one Oscar, right there, to Anna Asp and Susanne Lingheim), and some of the most ravishingly sumptuous cinematography ever committed to celluloid (another Oscar, to DP Sven Nykvist) in the opening scenes of this three-hour-plus epic tracing a couple of traumatic years in the life of Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and Alexander (Bertil Guve), though to all intents and purposes we can forget Fanny, who is barely in it, and switch out the first name Alexander for Ingmar. There’s no real doubt what’s going on here and who it’s really about.

The film divides neatly into two parts, Before and After, with a kind of happy ending coda tacked on at the end, the watershed being the death of the father of Alexander (and Fanny). Before then we’ve been introduced to the whole massive Ekdahl clan, a well-to-do, liberal theatrical family just preparing for the Christmas festivities in the first years of the 20th century – candles are lit, tables are laid, servants are harried, children are chivvied and the family assembles for one of those upstairs/downstairs events where everyone behaves much as you expect from having watched many things like this before. One of the servants ends up in bed with one of the men from upstairs, one family member has money worries, a longterm “secret” relationship bubbles along in the semi-open as the family pretends it isn’t happening. And so on.

Bergman reassures to deceive, laying on the colour red – carpets, walls, whole rooms – and the lush interiors, the sense of hail-fellow-well-met bonhomie to this degree the better to contrast with what is to follow, when Fanny and Alexander’s father, theatrical old buffer Oscar (Allan Edwall) dies, and in short order their mother marries again, to a bishop, only realising afterwards that she’s made a terrible, unalterable mistake.

The mother and the bishop were meant to have been played by Bergman old hands Liv Ullmann and Max von Sydow but instead Ewa Fröling and Jan Malmsjö take the roles. Both rise to the challenge, Fröling helped by the fact that she resembles Ullmann a touch, whereas Malmsjö, a song and dance man, is remarkable as the bishop whose sanctimonious brand of pious Christianity may or may not be just the surface decoration on top of something even more unyielding and cold beneath.

The source of Bergman’s complex relationship with religion and Christianity is revealed in increasingly unpleasant/abusive scenes set in the bishop’s home, where the cleric sets about “fixing” Alexander’s vivid imagination (a tendency to tell tall stories). Here, the cleric’s mother and sister dress in sober clothes and the house is decorated in whitewashed walls and furnished with simple wooden tables and chairs – all very nice if you bought them in a moment of Shaker-inspired interior-design frenzy, less so if that’s all there is and the temperatures outside (and inside) are sub zero.

That’s all there is to this film. He (sorry, they, the kids) live in the lap of loveliness, dad dies, then they don’t, and what was once all diamonds is now rust. Love is replaced by tough love. Plenty with austerity. Colour with monochrome. Kindness with strictness. It would all seem too simplisitic except that Bergman lays on the surface detail, interior and exterior decoration to a level that is boggling. Similarly, the acting is rich and vivid, occasionally shading deliberately into pantomime, while Bergman gives the lie to the idea that he’s somehow all about naturalism with moments straight from the melodrama playbook – a thunderbolt and flash of lightning at the key encounter between the bishop and Alexander which is so cliched it’s (deliberately?) amusing.

Neither Pernilla Allwin or Bertil Guve, who play the titular kids, made a career in acting, but both are excellent, Bergman carefully never exposing them to direct comparison with the likes of Jarl Kulle (who plays their fun-loving uncle, and who you might remember from Babette’s Feast, another winner of the Best Foreign Language Oscar) or Gunn Wållgren, the real star of the show, playing the ageing materfamilias around whom the massive clan constellates.

The film wasn’t even designed as a film. Instead Bergman conceived it as a TV series, which was meant to have been released first (and would have probably ruined the film’s Oscar chances if that had happened) but in the end came a year later and clocks in at five hours plus change. The TV series itself was also eventually edited together, so if Bergman-to-the-max is what you’re after, then that’s the way to go. Bergman himself preferred the long-long version (and there is an even longer cut somewhere, approaching six hours, which was his absolute favourite).

As for “final film”, Bergman continued working for another 20 fruitful years. He always was a tricky customer.

Fanny and Alexander – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022