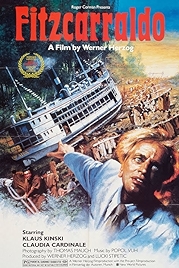

The “conquistador of the useless” is how Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald – known by the Peruvian locals as Fitcarraldo – is described at one point in Werner Herzog’s fourth collaboration with actor Klaus Kinski. It helps, watching this mad epic conceived on the grandest of scales, to remember that Herzog often described himself that way too.

The story is as big as the character of Fitzcarraldo, an obsessive opera-lover with a string of failures behind him, like the Trans-Andean railway that never went anywhere, or the ice-making business with not enough demand for ice locally to make success a possibility. As Herzog raises the curtain, Fitzcarraldo’s latest plan is to build an opera house in the middle of nowhere and get the great Enrico Caruso to sing there. To do that he needs money. And to get that he proposes dragging a cargo ship over a mountain to another river, where his monopolisation of all the waterborne trade will make him a wealthy man. If it comes off.

That’s what the film is about – a man with an operatically mad idea carrying it out, driven not by practicality but by dreams. Every time Fitzcarraldo hits an obstacle to progress, out comes the wind-up gramophone and on go the Caruso records. Energised, Fitzcarraldo moves on.

It’s a true story. There was a man called Carmen Fermin Fitzgerald, known as Fitzcarrald, and he did take a ship over a mountain. But he did it disassembled. This Fitzcarraldo transports the ship in one piece, with block and tackle and ropes. Even more remarkably so did Herzog. What we see Klaus Kinski’s character doing, Herzog himself was doing – hauling a ship over a mountain, plus taking care of a vast crew, his cast, plus 1,000 local Indians, and shooting a film as he did it all. It’s worth remembering that the original Fitzcarrald’s ship weighed 30 tons; Fitzcarraldo’s (and so also Herzog’s) weighed 320.

Tales from the undertaking are legion and, like Apocalypse Now, which Fitzcarraldo apes in ambition, there is a separate film about the making of the movie, Les Blank’s Burden of Dreams, which goes into the deaths, attacks by unhappy locals, the logistics of the endeavour, and includes footage of the original Fitzcarraldo, Jason Robards, before illness forced him to pull out.

There were also snake bites, a plane crash, arrow wounds and emergency surgery conducted at night on a table while Herzog himself held the light and tried to keep the mosquitoes away. Herzog even took prostitutes along, at the suggestion of a local Catholic priest – an undertaking this big needs camp followers, the cleric counselled. It’s like a medieval army on a huge campaign.

Kinski, as in all the other Herzog/Kinski collaborations – Aguirre, Wrath of God, Nosferatu the Vampyre and Woyzeck by this point – was impossible to work with and there was constant tension with cast and crew. At one point a local chief made the offer to Herzog to take Kinski out into the jungle and kill him.

As in Aguirre, thematically a sister film, and also about a reckless adventure on a river, Kinski is the embodiment of the swivel-eyed nature of the enterprise, both Fitzcarraldo’s and Herzog’s. His performance is big to the point of absurdity and Herzog’s film is also big, a bit baggily so here and there. And yet it succeeds, by sheer force of will, perhaps, but also eased along by the superb work by director of photography Thomas Mauch, a man with an eye for a widescreen composition and richly saturated colours.

He’d worked on Aguirre too, as had the German band Popol Vuh, whose incantatory soundtrack lends the whole thing an almost religious aspect.

By the end Herzog has triumphed but is clearly exhausted. As his majestic final scene plays out – orchestra, choir and opera singers in full flight on the top deck of Fitzcarraldo’s battered ship – in the background you can see boats powered by the sort of modern outboard engines no one had in Fitzcarraldo’s time. It is such a magnificent and emblematic final scene, though, one of the best ever filmed, that you can understand why he let it go.

Fitzcarraldo – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023