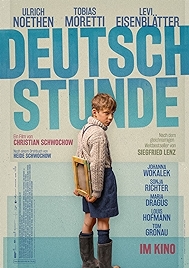

Why did the Germans in the 1930s fall prey to the Nazi ideology? 2019’s The German Lesson (Deutschstunde) is a bracing story both about the Germans and for the Germans, who might not relish what writer Siegfried Lenz has served up, though director Christian Schwochow sugars the pill with images of austere beauty.

Told in flashback from a jail cell where the barely adult Siggi is now a problem prisoner in post-War Germany, the story follows Siggi into his own past, growing up on the windswept Baltic coast with a father whose devotion to his policeman’s job came before else.

It looks like an everyday German dedication to duty – “Pflicht”, to borrow a word that’s much used in this movie – that’s driving Jens (Ulrich Noethen), particularly in his dealings with Max (Tobias Moretti), a local artist and old family friend. All of Max’s paintings have been classed as degenerate by the Nazis and so when Jens seizes and destroys his work, expressionist daubs that couldn’t hurt anyone, it can be seen as Jens just doing his duty.

Except Jens prosecutes that duty with a vigour that’s almost monomaniacal and seems blind to calls of duty of any other sort – duty to friends, to family, to wider notions of fairness or justice, to personal intergrity and a sense of self.

Siggi’s story is one of a boy coming between two men and two notions of society and philosophies of living. The father on one side, and Max (Siggi’s godfather, significantly) on the other.

Problematically, The German Lesson has said pretty much the bulk of what it has to say on this subject in its first half hour. There is then a lull with not much in the way of development until the last half hour or so when the action cuts to some years after the war has ended. Jens is released from an extended detention by the allies and returns home to resume his job as local policeman. New times, new approach, right?

Here the film again takes wing, as actors and director sketch out the post-war situation – the family’s supreme indifference to Jens’s return, his behaviour and the way old faces from the Nazi past keep popping up, in positions you’d not expect old Nazis to be in.

There is an earlier adaptation of Lenz’s novel, made for TV in 1971, when the embers of 1968 were glowing and a younger generation of Germans was asking questions about what the older generation had been up to during the Nazi period. It was the time of the New German Cinema, of directors like Fassbinder, Schlöndorff and Wenders.

The questions seem less urgent in the 21st century, but the actors rise to their task – it’s their duty, you could say. Noethen is particularly good as Jens, suggesting and teasing about the true nature of Jens’s character. Is it the devotion to duty that drove Jens (and by extension the Germans) into the hands of the Nazis, or is it somehow the other way around, and the devotion to duty springs from a kind of Nazi hard coding?

Moretti is also on great form as Max, a winning mix of lightning-fast actorly reflexes and a relaxed style of delivery. As for Siggi, he’s played as a boy by Levi Eisenblätter, and how fantastically good Eisenblätter is at being furtive, secretive, closed off, something Tom Gronau also captures as the grown-up Siggi.

The cinematography and production design are exemplary. Frank Lamm has shot a number of good-looking German TV shows – Bad Banks (starring Paula Beer) and Dogs of Berlin among them – and shoots the spare wide open spaces of the Baltic coast, the seagulls wheeling, the mud flats stretching to infinity, to suggest a Protestant starkness to everything, while the interiors of the houses are similar, plain, unadorned, frugal. The message of The German Lesson may be tough, but the wrapping is beautiful.

The German Lesson (Deutschstunde) – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023