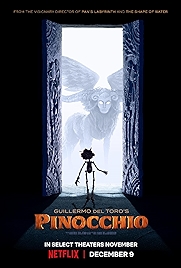

Guillermo del Toro was everywhere at the beginning of 2023, promoting what increasingly became known as Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio in the Oscars window between Christmas and awards night. Tirelessly, enthusiastically, he made the case that his film should have been in contention not just for Best Animated Feature but also Best Picture. Why shouldn’t animation be treated as seriously as live action, he argued. At one point while in London del Toro got stuck in a lift between appearances. That, too, ended up on social media as part of the promotional caravanserai, an example of turning that frown upside down.

In the end Pinocchio won Best Animated Feature. I suspect the only real contender was Marcel the Shell with Shoes On, for sheer innovative cuteness if nothing else.

But. Pinocchio. When del Toro’s hit the screens, it had to jostle for attention. Matteo Garrone had made a live-action Pinocchio only three years before which was about as faithful to Carlo Collodi’s original as anyone could want. Definitive, in storytelling terms if nothing else. And at the point where del Toro finally started getting his big guns lined up behind a production that had been stuck in development hell for years it turned out that Robert Zemeckis had also started working on another adaptation, a live-action Pinocchio, with Tom Hanks and Joseph Gordon-Levitt starring. Zemeckis’s Pinocchio had the distinction of being faithful to the original too, if by “original” we mean Disney’s 1940 animation, a dark classic.

So maybe, with Garrone on one side and Zemeckis on the other, del Toro felt as if there was too much faithfulness about, and so felt encouraged to branch out in directions new in his animated version.

It’s still a story of a wooden boy with a nose that grows longer when he tells lies going out into the big wide world and having adventures. But that branching out is the least successful aspect of this beautifully animated film, exquisitely voiced by the likes of Ewan McGregor (funny as the talking cricket), Christoph Waltz as Volpe (a combination of the Collodi’s fox and the ringmaster of the circus Pinocchio runs away to), David Bradley (Geppetto), Tilda Swinton (two roles, as a wood sprite who gives Pinocchio life and as her sister, Death) and in particular Gregory Mann, whose voicing of Pinocchio is the best thing of all. Mann, aged 13 maximum when this was made, imbues Pinocchio with an almost unhinged can-do naivety, an ADHD energy that is genuinely winning.

There are songs, by Alexandre Desplat, that are more Broadway than Billboard, and one of the film’s good running jokes is that every time the cricket (McGregor) is about to burst into song he’s interrupted, as if a repeatedly thwarted McGregor has been waiting all the years since Moulin Rouge to let loose with a big song.

It’s the changes I take issue with. None of them improve the original and some of them are really damaging. To do away with the interplay of the fox and the cat in the original story – a standout in Garrone’s version, and the 1940 Disney version (I have not seen Zemeckis’s Pinocchio) – is a straight-up mistake. Moving the action from the 1880s to the 1920s, to allow for the inclusion of Mussolini and his fascists acts as a kind of political wallpaper but not much more and seems fatuous. Geppetto’s back story – a son lost in the First World War in the bombing of a church – muddies the waters. This isn’t Geppetto’s story. Other, tiny, changes, like giving the cricket an elaborate name, Sebastian J Cricket, seem like change for the sake of change. Not better, just different.

A good story replaced with one that’s less good, and less dark. Properly sinister characters replaced with ones who don’t measure up. This is odd, considering it’s del Toro – of The Devil’s Backbone and Pan’s Labyrinth.

But the good stuff is good. The animation, by Mark Gustafson and team, gothic tinged and endlessly agile. The voice cast, already mentioned but Cate Blanchett is in there too, as Volpe’s monkey sidekick (screams and howls aplenty, not much recognisable Blanchett) and, behind it all, a big idea – it’s mortality that makes all of us real boys. Being made of wood is all very good, but only the prospect of death really makes us truly alive. I liked that.

Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023