Howard Hughes had almost finished his action-packed, stunt-driven epic Hell’s Angels, at vast expense, in 1928 when silent movies were suddenly made obsolete by the vast success of The Jazz Singer. So he did what any mega-rich tycoon who just happened to own a film studio would do – he remade it.

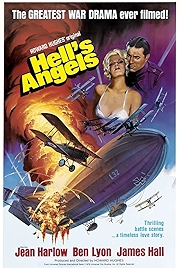

Out went his female star in the process. Greta Nissen was Norwegian and had a heavy accent, and so she became one of the first casualties of the talkies, which destroyed many an established career (which is what the plot of Singin’ in the Rain is all about, after all). In came unknown 18-year-old Jean Harlow to fill the gap, while Hughes also brought in the rookie James Whale to help direct the new talking sequences.

Hughes kept as much of the old silent film as he could. Which is why there are three directors named on the IMDb entry for this film (though only Hughes’s name is on the screen credits). It breaks down like this: Edmund Goulding shot the silent sequences set on the ground (sound has been added afterwards but you can easily make them out, not least because the frame speed is all wrong). Hughes shot all the aerial sequences; and Whale did all the new dialogue sequences.

The film is designed as a vast Hollywood entertainment, with all the major food groups – action, comedy, romance, drama – and tells the story of a Cain and Abel-alike pair of brothers, one a solid plodder, the other a dashing gadabout. The story kicks off in pre-First World War Germany, where dull Roy (James Hall) and feckless Monte (Ben Lyon) are carousing with their German friend Karl (John Darrow), a fellow Oxford student who’s going to find himself on the other side of the great divide when the lights start going out all over Europe.

The story only half-heartedly follows Karl, who has mixed feelings about fighting against a country he knows and loves, and is much more interested in Helen, a va-va-voom temptress of almost biblical scale, played with all sirens wailing by Jean Harlow. Harlow clearly cannot act – James Whale shut down production for days to bring her up to speed – but she has all the wanton sexiness a true star needs. Who needs acting? Helen is boring Roy’s squeeze but the moment the rascally Monte claps eyes on her, and her on him, the sparks are flying.

Again, Hughes sets this up but he isn’t as full-throated in following the Roy-Helen-Monte threeway as you might expect, though there are enough scenes of Harlow’s tight young breasts loose under her sheer pre-Code dresses that we get the idea. Hughes was a tit man, let’s not forget.

What Hughes is really interested in is the aerial stunts. And once the story has engineered both brothers into signing up for the Royal Flying Corps (the forerunner of the RAF), he has all the pretext he needs.

Really, Harlow apart, these are the reason why the film still flies today. They are properly spectacular. An early taster, of a vast German airship heading to bomb London with Karl on board, is impressive enough – the way the Zeppelin moves like a whale between vast billowing clouds, the on-board sequences on sets that are marvels of art nouveau design and technical sophistication. But it’s the climactic aerial combat sequences that are what the film is really all about. Featuring First World War biplanes flown to showcase their manoeuvrability, they’re masterpieces of aerial choreography, cinematography and editing. Apart from an aerial bombardment sequence, which uses models, it’s nearly all done for real. And when you’re after realism, real wins every time.

Three pilots and one mechanic died in the making of this film and Hughes himself ended up in hospital after crashing a plane while trying to impress the ex First World War hotshots he’d hired as stunt fliers. They’d warned him the plane he was taking out was hard to handle but he went and did it anyway.

It’s a good-looking film and much of it was hand-tinted, not much of which has survived the intervening decades, though the early duel scene – Roy stepping up to trade swords with a cuckolded husband after the cowardly Monte flees Germany – in a vibrant blue gives an indication of how vivid the film must once have looked (incidentally, the composition of this scene seems also to have impressed Ridley Scott, who borrowed its silhouette looks for The Duellists). For lovers of very early colour films there’s also a two-strip colour sequences set at the ball where Helen first meets Monte, which is the only non-monochrome footage of Harlow.

Monte, incidentally, is not the hero. The sexy guy may get all the girls but he doesn’t get any kudos. It’s the dullard we’re meant to root for. Hollywood would tweak this equation down the line. As for the bad, sexy blonde bombshell who could have any man, Harlow made the mould that’s still in use.

Hell’s Angels – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022