HBO’s documentary A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks does a great service for ignoramuses (like me) who mistakenly had Parks pegged as the guy who directed Shaft and a few other films and maybe dabbled in photojournalism earlier in this life.

He was so much more. Born in 1912, Gordon Parks came of age as the Depression was taking hold and by his own admission (in archive interview footage) would probably have lived the life of the career criminal/hustler if he hadn’t become fascinated by some photographs in a magazine and picked up a camera. Parks had real talent and was a hard worker and by the end of the 1930s was taking portraits as well as turning out snaps for newspapers – students graduating and the like – before his big break came, when he landed a scholarship with the Farm Security Administration, where a lot of talented photographers – Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans – cut their teeth.

Here he developed the technique which was to serve him so well for the rest of his life – get to know your subject, win their trust and build a relationship before attempting to photograph them. That’s how he got the famous shot of Ella Watson, a black cleaner at the FSA, in a picture shot in front of the Stars and Stripes and titled American Gothic, Washington DC, an ironic reference to Grant Wood’s painting of a white American farmer and his wife.

After several years at the FSA, in 1948 he collaborated with Ralph Ellison – of The Invisible Man fame – who came up with the manifesto principle that a photograph needed to be both “document and symbol”. It made more concrete what Parks was already doing and refocused him as a documentary photographer with an activist’s motivation.

A job at Life magazine followed – he was the only black man on staff – and here director John Maggio rightly lingers to give us instance after instance of the great work Parks did there, starting with Harlem Gang Leader, his spreads on Red Jackson, with whom Parks spent so much time before picking up a camera that Jackson started to goad him about it.

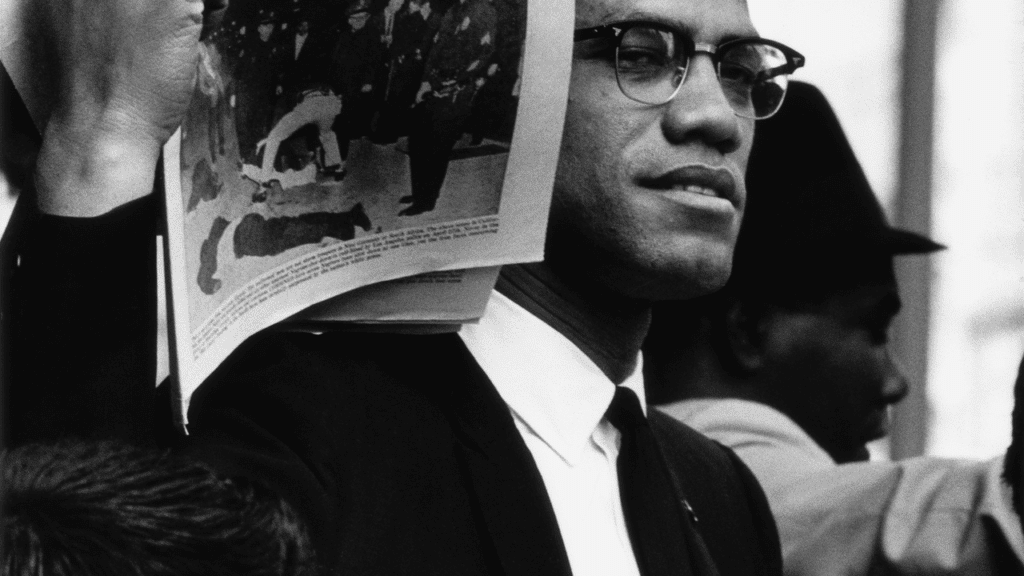

Parks was versatile and as well as turning out exemplary work for Life was also doing portraiture and fashion work – stuff not unlike Irving Penn. But his best work is in Life – the spreads on black segregated lives in Alabama, shot in colour to bring home that this was the here and now USA. The “American crime series” shot in 1957, full of great images, like the one of a cop with a flashlight bending over a body on the ground at night. His 1960s shots of Malcolm X and Muhammad Ali.

In archive footage you can see how he got so close to his subjects. Parks is a relaxed and charming man with a warm and wicked smile. He brings out a fondness among the talking heads who turn out to sing his praises. Nelson George talks about the “elegance” of Parks’s photos. Spike Lee talks about his own documentary, 4 Little Girls, and how he borrowed Parks’s method of striking up a personal relationship with his subjects. Ava DuVernay, director of Selma, talks about borrowing his way of using a camera as a “weapon”. Richard Roundtree, star of Shaft, remembers Parks sending him off to his own tailor to find the right clothes to play John Shaft, aka “the black James Bond”, and points out with a chuckle that only years later did he realise that Shaft is in fact Parks.

Perhaps less successfully is the inclusion of some present-day black photographers who have been inspired by Parks. Nothing wrong with the work of any of them, it’s just that there’s less time for Parks, whose side career as a composer is ignored.

Roundtree also reminds us that Shaft was a massively successful film – Isaac Hayes’s Oscar-winning theme song helped. It launched the blaxploitation genre and made a lot of money for the studios but it didn’t do many favours for Parks, who found himself unable to get the sort of high profile, big budget work that a white director with a massive breakout hit would have been offered.

It’s straightforward racism, of course. “I consider this my world,” says Parks early on in an old interview, responding to a question about being a black man “living in a white man’s world.” It is this nobility of spirit and steely but unstrident determination to rise above the slings and arrows that set him apart. And the talent, of course.

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2021