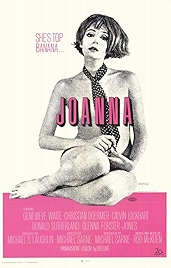

“The baroque signifies rebellion against the constraints of classicism,” is the key line in Michael Sarne’s Swinging London movie from 1968, Joanna. A more-is-more display of the excessive, it attempts to get several quarts into a pint pot, to import some Godard smarts and Fellini flash into staid British film-making and generally to baroque’n’roll things up as much as it can.

In what verges on the incoherent but just about sticks to a story, the thin plot follows new-in-town 18-year-old Joanna (Geneviève Waïte) as she meets people on the London scene, sleeps with men, attends art school when she can be bothered (which is where the line about the baroque comes in) and has punishing existential discussions about the meaning of life, God, death and all that, all while wearing a succession of groovy outfits. This film does not lack for colour, something it announces in its opening scene, when Joanna arrives in a black-and-white London on a train into Paddington Station, the visuals suddenly flipping into rainbow hues the instant she opens the train door.

From all these decades later, two things really stand out. Joanna is the hero of this story. She’s a woman with agency, which isn’t that common at the time. And she has a black friend, Beryl, a character who threatens at any minute to take over the film, largely on account of Glenna Forster-Jones’s vivid playing – she’s got real presence – but also possibly because Sarne wants her to but isn’t able to go there. Beryl also has a brother, the handsome Gordon (Calvin Lockhart), an urbane, intelligent and educated guy who will provide late-arriving love interest for Joanna – “I wish you were white,” Joanna squeaks breathily (her tone throughout) when she realises she is falling for him.

This bracing directness vis a vis race – black people are regularly referred to as “spades” but it doesn’t seem malicious – is one thing but incoherence is the main charge against this film. Which isn’t quite fair because that’s exactly what Sarne is trying to achieve in his collaging together of everyday events with fantasy sequences, frequent shifts of location, new places, new faces, in an attempt to convey the vertiginous sense of hedonism unleashed.

Sarne was something of a 1960s face himself – a twentysomething pop star and actor as well as writer and director, he also ran through a good number of women (including Brigitte Bardot fresh from her honeymoon with Gunter Sachs, plus Waïte herself) – and though he’s often pegged as a dilettante, he gets the 1960s in ways many older writer/directors didn’t. From Sarne’s vantage point the 1960s are a more female, less exclusively white decade, but as one male character says at one point “One gets the feeling that all women have achieved from emancipation is the privilege of getting laid,” in essence summing up the feminist take on the decade (great for guys, less so for girls) in a line.

He also gets that the Swinging Sixties were only Swinging for rich people. Most of it in this film is done in the presence, or with the coin, of rich aristocrat Lord Peter Sanderson, a chance for Donald Sutherland to be charismatically dazzling, even though he’s playing a silly-arse, gigantically inbred toff with a terminal illness.

It’s a strange film, not entirely satisfying but endlessly fascinating, at its best when it stops worrying too much about the plot and just focuses on catching moods, atmospheres and impressions.

It looks great on the British Film Institute restoration (linked to below) and an added bonus is Scott Walker singing the theme tune, a Tony Hatch/Jackie Trent song that has absolutely nothing to do with the film but which does give Sarne a licence to get some hoary 1960s favourites off his chest, like Waïte wandering through Trafalgar Square and causing all the pigeons to take flight.

Joanna – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023