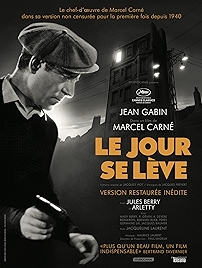

Le Jour Sè Leve is a prime example of a film in the doom-flecked “poetic realist” style which flourished in France before the Second World War and we’re lucky to have it at all. When RKO set out to remake it in 1947, as The Long Night, they bought up and destroyed all the prints they could find. But not all of them, obviously, because here we are.

It didn’t go too well for the remake (the New York Times described the 1936 French original as “in every respect superior to this new job”) even with Henry Fonda in the key role, as the murderer reflecting alone in his room as night gradually gives way to day and justice approaches.

In this original it’s Jean Gabin as the killer, and he definitely is a killer. We hear the shots, we see his victim staggering out of his room and tumbling down the stairs, where a blind man tap-tap-tapping his way up to his room finds him. The police are soon on the scene.

From here Marcel Carné and writers Jacques Viot and Jacques Prévert give us chapter and verse on how it came to this. As Gabin’s François ruminates up in his attic, three extended flashbacks tell us his story – how he, a forge worker, met and wooed a charming flower girl called Françoise (Jacqueline Laurent); how Françoise’s silly head was turned by the womanising music hall turn Valentin (Jules Berry), and François consoled himself with Valentin’s cast-off, libidinous free spirit Clara (Arietty); and how François and Valentin eventually had the showdown which resulted in Valentin’s death.

From here it’s a hop and a skip to the unavoidable hand of justice, but not before François has made a rousing speech from his attic window to the gathering crowd below, a forceful example of why Gabin at the time was the country’s biggest star.

The support turns are great. Berry in particular, who pretty much reheats his creepy, winking womaniser from Le Crime de M. Lange from three years earlier – but it’s a role worth reheating. Arietty (it seems to be a rule of French cinema of this era that there has to be at least one mononymous star) is a worldly Clara and there’s even a shocking-because-unexpected nude shot of her to demonstrate her character’s free-and-easy attitude. And Laurent is entirely plausible as a sweetie pie with no idea whatsoever about the world, men in particular.

That all said, it’s Gabin’s show and a great example of the sort of terse but essentially decent masculine roles that were his forte.

There’s a class angle too, as so often in Gabin movies, honest son-of-the-sod François versus sleek sophisticate Valentin. But even in the scenes set in the foundry, where François works in the thankless, lung-shredding sandblasting section, Carné dresses everything up in pretty clothes. When François walks Françoise home on an early date in the relationship going nowhere, the lane they walk along is like something from a fairy tale (before Valentin’s big bad wolf arrives). The roofline of the neighbourhood where François lives is also cute, with nods to German expressionism, in a toned down, prettified gingerbread house kind of way.

Poetic realism is an apt label and both elements pull their weight – things look real but softened, stylised but not too much. Noir before noir, some call it, though noir has a hard visual edge which Le Jour Se Lève isn’t after.

Carné pulls off some bravura stuff late on. As the crowd gathers below François’s window as day breaks (Daybreak is the English language title), Carné is out there in the crowd too with his camera, in shots designed to elicit a “how the hell did he do that?”

But the technical is in service of the lyrical in this film. Along with Carné’s Quai des Brumes, this is the pinnacle of poetic realism.

Le Jour Se Leve – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023