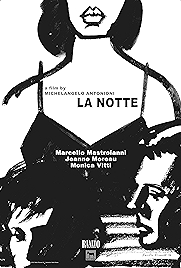

It’s called The Night, the IMDb tells us, though I’ve never heard Antonioni’s 1961 drama called anything but La Notte. So let’s use the original title. It’s pithy. As Italian phrases go this one is not hard to say and it’s distinctive. There are plenty of films called The Night already.

The title is as stark as the film’s opening moments. The credits are written in an unfussy sans serif font. The theme music is atonal. The first images we see are of glass and steel buildings shot to emphasise their angularity. La Notte is the mid-century modern movie – sleek, unadorned, made out of good materials and not entirely comfortable.

Isn’t life a drag? What is the point of it all? How do human emotions co-exist with the daily struggle against existential pointlessness? Putting flesh on these beatnik notions are Marcello Mastroianni and Jeanne Moreau as a married couple who we meet getting a sharp dose of real reality – they’re visiting a friend in hospital who is dying – before they fall back into the listless routine of their everyday lives.

They drive around, they walk around, they hang around, unable to communicate properly with each other. Instead they grab on to passing novelty. In the hospital where their friend is dosed up on morphine, successful but bored writer Giovanni (Mastroianni) nearly has sex with a crazy patient on the same corridor who appears to be in the hospital on account of her nymphomania. Out on the streets, Lidia (Moreau) pulls “fuck me” faces at men she doesn’t know.

If modernist music is tuneless, and modernist architecture formless (it merely follows function), then modernist cinema must be… plotless? Antonioni seems to be taking this line in a story that isn’t a story, about two people whose mysterious relationship is the only thing to really hang on to. Are they still fascinated with each other and play-acting at boredom as part of some protracted cool tease? Or genuinley, properly bored bored?

The “action” all takes place over one day and the film breaks down into two halves – day and night. The first is all modernist compositions – hard angles, light and shade, high rise buildings going up, long avenues heading to the vanishing point. The second arrives after a palate cleanser at a club – where a remarkable floor show featuring two black acrobat/contortionists might be trying to say something about primitive, pre-Modern existence. And then on to The Night, a grand party, the sort where you might expect Sean Connery’s 007 to turn up, where Giovanni meets Valentina (Monica Vitti), another bored cynic whose money means she never really has to confront anything at all if she doesn’t want to.

There are parallels with La Dolce Vita, which Mastroianni had made the year before with Fellini, and which was also about the existential challenge of what to do with yourself once survival is no longer an issue.

After much sliding of the camera into compositions that would eventually become cliched – two faces, one in profile, one head on, one in the light, the other in the silhouette, stark shapes, as if stills photographs had somehow come to life – Valentina and Giovanni settle down for the film’s centrepiece conversation, a verbal duel in which each party tries to outdo the other in terms of existential anguish.

It looks a bit ludicrous at this distance, but strangely, for a film notable for not much happening, it’s never boring. Antonioni’s compositions are exquisite, and he moves his characters about like chess pieces. Its stark cinematography by Gianni Di Venanzo is worth watching the film for alone and the Criterion restoration really sharpens up its already sharp looks. (Di Venanzo died young, aged 46, otherwise he’d be a much bigger name).

The dubbing is awful, but it is the dubbing as it originally was, too loud and with bad ambience. And it matters in this film because there’s something of the nightmare reverie in Antonioni’s visual approach which the voices undermine.

Ironically, failure to communicate, or the impossibility of communicating properly, person to person, across the existential chasm, is the film’s big idea. Antonioni had had a go at it the year before with L’Avventura and he’d have another stab at the subject again the year after with L’Eclisse, with Monica Vitti, Antonioni’s lover at the time, the link between all three.

Antonioni died in 2007 aged 94, on the same day as Ingmar Bergman. He spent the last 22 years of his life unable to speak, after suffering a stroke and famously gave the Oscars’ shortest acceptance speech (“Grazie”). The cosmic irony of his own inability to communicate in his later years was surely not lost on him.

La Notte – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022