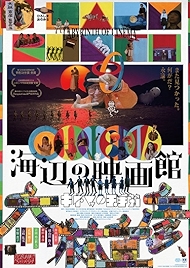

At a certain point words won’t do. So it is with Labyrinth of Cinema, a wild kaleidoscopic three hours designed as a farewell by an old man to an art and craft he has loved, and to the world he’s been living in for around 80 years.

The man is called Nobuhiko Ôbayashi and he’d been making films since 1944 – his first one minute short – when he was eight years old. In 2016 Ôbayashi was diagnosed with terminal cancer while making his previous movie, Hanagatami, and told he had only three months to live. He finished that film and, amazingly, started work on this next one, designed as a vast summing up of the whole damn thing and a wave goodbye with a song in his heart.

Here’s where the words start to fail, though things start out straightforwardly enough. A cinema in the city of Onomichi (the director’s home town) is closing down and decides to go out with a bang with an all-nighter of war movies. (Ôbayashi has spent his career making anti-war movies, and so this is all part of his cosmic joke.) A quick introduction to several characters – the aged owner of the cinema, her dedicated old-school projectionist, a pretty teenager called Noriko (Rei Yoshida), a film buff called Mario (Takuro Atsuki), a former monk who’s now a street punk called Shigeru (Yoshihiko Hosoda) and an academic film historian called Hosuke (Takahito Hosoyamada).

At a certain point, after we’ve already noted that Ôbayashi is slathering on the montage and working his way through every effects setting in Final Cut Pro, Noriko suddenly finds herself inside the film instead of in the audience watching it, and is closely followed by Mario, Shigeru and Hosuke, in a development reminiscent of Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo, though to more ambitious purposes.

Ôbayashi sets to with a young man’s enthusiasm for an old man’s passions, recreating the genres of his youth – the musical, the samurai epic, the yakuza movie, a geisha drama – inserting his characters into each and then yanking them out again and sitting them back in their seats. Gradually it becomes clear that Ôbayashi is most interested in the war movie and its representation of several significant conflicts. The Boshin War, or Japanese Civil War, of 1868, the Sino Japanese War of 1894 and eventually the Second World War.

Ôbayashi slides between three vantage points – his heroes are either sitting in their seats watching the action on the screen, inside looking on or, increasingly, inside taking part. The occasional character from “inside” also escapes into the outside world, just to mix things up a bit more.

The most remarkable thing about the film is Ôbayashi’s command of tone. Labyrinth of Cinema starts out in a register that wouldn’t be out of place in an episode of The Monkees. Zany, quickfire, amusing, irreverent etc, with Japanese wartime xenophobia acting as a sort of running joke. But as Noriko, Shigeru et al find themselves becoming more involved in the on-screen world, gradually Ôbayashi wheels the entire film around, as if turning a supertanker. And with the first mention of the name Hiroshima things step into more elegiac territory and a terrible sense of foreboding is established, made only more poignant by the fact that Noriko, on screen and off, seems to have fallen in love. Cinematography and soundtrack follow suit, swapping out discord for beautifully framed and lit imagery, and a score that surges plaintively like something out of Brief Encounter.

Here, as Ôbayashi abandons his arch playfulness and replaces it with a tenderness that’s almost too much to bear, the misgivings fell entirely away. Tying together fact (the cinema audience) and fiction (what they’re watching), the present and the past, Ôbayashi is working at a meta level but also insisting on specifics – not for nothing are a film historian and a film buff on hand, and even over the end credits a voiceover is telling us the name of the song we’re listening to, who wrote it, sang it etc.

Simultaneously massive and yet operating on a simple human scale, it’s a remarkable achievement and a hell of a way to go. That’s the director, with his back to us at the end, tinkling away on an old out-of-tune piano. By the time most audiences got to see his film in 2020, he was dead. Labyrinth of Cinema is his requiem.

Labyrinth of Cinema – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022