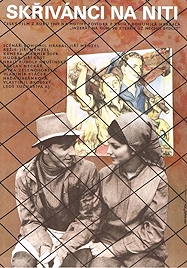

Production on Larks on a String (Skrivánci na niti) started during the Prague Spring, an eight month period in Czechoslovakia when political liberalisation under the rule of new Communist First Secretary Alexander Dubček looked set to transform the country. It was not to be. By August 1968 the experiment was over, Soviet tanks were rolling in to the Czech capital and Dubček had been deposed. Also kicked into the long grass was any chance of distribution for Jiří Menzel’s now completed film, which wasn’t seen until 1990, after communism collapsed.

Menzel is a master of straight-faced satire. In Closely Observed Trains he used a story about Nazis during wartime to comment on the communist regime, but in such a way that the authorities couldn’t get a glove on him. “What? No! I’m talking about the Nazi regime, obviously. What else would I be talking about…” etc etc

That’s not the case here. Though working again with writer Bohumil Hrabal (who also wrote Trains), Larks on a String is a much more heavy-handed work, though under it all it’s a plea for a raggedy, flighty, tender, undoctrinaire humanism that stands in stark contrast to ideologically driven political projects like communism.

The heavy-handedness is exemplified by the setting, a bleak and filthy scrap metal yard where – a voiceover tells us – the year is 1948 (is this a reference to Orwell’s 1984?), the proletarian revolution has been completed and dissident and bourgeois elements have been sent for re-education. These are represented by a Seventh Day Adventist who wants freedom of expression. A lawyer who believes in a fair trial. A professor who wants to be able to discuss philosophical ideas freely. A saxophonist (a bourgeois instrument). All men. Meanwhile, in another part of the scrapyard is a gaggle of women, all there for daring to want to escape the country.

These are our “larks on a string”, silly humans who’ve had the wrong thoughts, said the wrong things, wanted the wrong products, being taught a lesson or two as they unload wagons full of ancient standup typewriters, move bales of compressed scrap metal about using gigantic electro magnets, dive out of the way as runaway iron drums full of god knows what come bouncing towards them.

Stalinist gulags are the obvious target, or maybe Menzel also has Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution in mind, which sent whole sections of society – the “elite” – off to work on the land and wrecked the economy in the process (as if his previous brilliant idea, the Great Leap Forward, hadn’t wrecked it enough).

While the scrapyard prisoners work, they talk. But Menzel and Hrabal aren’t quite as interested in what they have to say as they are in two love stories that exemplify what humans are really like. In one, one of the guards marries a local gypsy woman. A wedding feast, drinking and carousing, followed by the couple moving into a new-build block, where gas on tap, electric light and the mod cons of the era of progress surprise and delight them. In another, two of the scrapyard’s inmates move from making eyes at each other to declaring love behind heaps of discarded steel, to finally getting married, though she’s not actually at the ceremony because of some infraction she’s committed. Hence the absurdity of Pavel (Vacláv Neckár, who was also Menzel’s star in Closely Observed Trains) having to marry a stand-in for Jitka (Jitka Zelenohorská).

Throughout, while Westerners of a hippie persuasion were railing against consumerism and surface frippery, Menzel and Hrabal celebrate these as the fullest expression of the human soul. Drinking, sleeping, eating, love-making and bathing are the noblest acts, says Pavel at one point, explicitly, while Menzel also makes it clear that beauty, technology, creature comfort, flirting, the silly surface “bourgeois” world of “stuff” is actually where most people live.

For a film set in a scrapyard full of heavy industrial remnants it’s surprisingly gentle. Too gentle to work as an angry political polemic, maybe. Characters disappear on the way towards the finish. They’re probably dead or in a gulag. As the curtain comes down, a young gypsy girl is being undressed and washed by an army officer and a party functionary. What’s going to happen to her?

Larks on a String – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022