The movie-as-oil-painting prize goes to The Leopard, Luchino Visconti’s majestic, magnificent, magical magnum opus from 1963, a contender in all the serious forums for best looking film ever made but also a triumph as an examination of a society, a politics and a psychology in flux.

It’s an adaptation of Giuseppe di Lampedusa’s only novel – a best-seller to this day – and follows it closely. There is no real plot, in other words, more a series of tableaux from the life of a mid-19th-century Sicilian prince as he and his family are buffeted by change, brought about first of all by Garibaldi’s revolutionary Red Shirts, busy unifying Italy (re-unifying, if we’re counting the Roman Empire era), soon to be followed by the arrival of the era of democracy and the end of the era of deference.

Life goes on for the Prince and his household, but he is wise enough to know it is all over and that the fat lady is about to sing. It’s this sense of the poignant slow fade – of a dynastic existence and of the man himself – that gives the film its power. Visconti, a Communist, doesn’t let his political leanings get in the way of a good story.

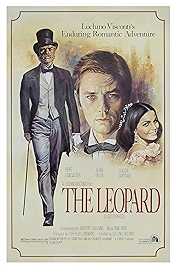

Shot in 70mm on Technicolor’s massive widescreen Technirama cameras, this is a big film in every respect. That starts with Burt Lancaster, somewhat improbably cast as the Prince, considering this is an Italian production. But his producers told Visconti that he needed a box-office name to bankroll the movie, and – first choice Laurence Olivier not being available – he reluctantly accepted Lancaster, who turned out to be inspired casting, as Visconti himself came to realise.

Just the right age, at 50, with a natural gravitas and a late-career interest in more psychologically driven roles, Lancaster’s Prince Don Fabrizio Salina is the embodiment of noble entitlement as the paterfamilias more aware than anyone around him that this the game is up for the nobility in Italy. From now on it will be a case of heads kept down, wealth enjoyed on the quiet, rather than the massively extravagant lifestyle and public adoration and respect the Salinas dynasty currently enjoy.

The film essentially follows the Prince, family and entourage out of wartorn Palermo and up into the mountains to the summer palazzo, where a series of showstopping, remarkably photographed events – a picnic, a procession through the town, a visit to church, a plebiscite on unification, a vast dinner, a visit by a representative of the new government hoping to co-opt the Prince, and finally a lavish ball which takes up most of the film’s final hour – are designed to reinforce the sense of just how much this family has, in terms of wealth and social clout.

For plot junkies, and acting as an eye-catching throughline, is the story of Tancredi, the dashing nephew of the Prince, a handsome chip off the old block and advocate for change who falls badly for Angelica, the daughter of local new-money rapscallion Don Calogero Salada (excellent Paolo Stoppa), the film’s comedic fallguy.

Tancredi is played by Alain Delon, contender for the title of world’s most handsome man at the time. Angelica is played by Claudia Cardinale, her waist eye-catchingly cinched to bruising point. Visconti, in case we don’t quite get what a showstopper she is, gives Angelica one of those spectacular filmic entrances during which all the men present fall silent and re-adjust their equipment (swords, scabbards and whatever else is hanging below), while the women look on forlonly, realising the lights have just all swung in the other direction.

Much is made of Angelica and Tancredi’s natural beauty, this being one of the “proofs” of the natural superiority of aristocracy – “We were the leopards, the lions. Those who take our place will be jackals and sheep,” the Prince says at one point, aware of where democracy is leading his class.

Beauty, at some level, is what the film is about. The more of it we see, the more keenly felt the loss. This gives full licence to Visconti’s obsessive eye for detail – hard to believe he’d started out as an austere neoralist – and to Giuseppe Rotunno’s almost absurdly luxuriant cinematography, composed with a painter’s eye.

It is film-making on the vastest of canvases, and yet Lancaster gives us enough peeps into the Prince’s soul, with tiny reaction shots mostly, to make this also a touching personal portrait of one man’s decline.

The Prince doesn’t die, as he did in the original book, but he is ageing, as is his world. In a brilliant late scene there’s a small duel between him and Tancredi – all done with the eyes – over Angelica, who might at this point stand for Italy. The older man and the younger, the aristocrat and the opportunist. We know how that’s going to end.

The full-length (186 minutes) Criterion version is the one to watch. Rotunno himself oversaw the 1980s restoration of the original elements, and Criterion’s transfer to digital catches the almost mad theatricality of his Technicolor lensing. The sound is fine if a touch tinny, which leaves Nino Rotta’s sumptuous score shortchanged slightly. Oh well.

The Leopard – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022