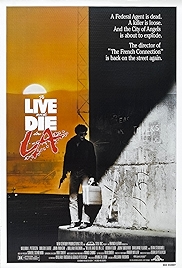

To Live and Die in LA – the title is almost an invitation. Its director, William Friedkin, though born in Chicago, did live in Los Angeles, and that’s where he died aged 87 last week (I’m writing this on 18 August 2023), till the end a combative, charming, rough-edged, cultured man of many parts. The director who gave us the magisterial The French Connection and the blood-thinning The Exorcist stumbled at the box office with 1977’s Sorcerer (for all its merits nowhere near as good as the film it’s based on, The Wages of Fear) and then as good as fell off the edge of the world with Cruising, a film that looks better now than it did in 1980, when queer S&M made more obviously for box office failure.

What to make of 1985’s To Live and Die in LA, which is lauded in some quarters and derided in others? From this distance it looks like an attempt by Friedkin to regain what he had lost, being an astute mix of what a gun-for-hire director might turn in for the genre producer who’d employed him, with enough “Friedkin” touches to remind any other producers out there that creativity hadn’t entirely abandoned him.

It’s a crime thriller with buddy-cop overtones and initially looks almost like the template for the Lethal Weapon movies – young hotshot cop with older, sensible, near-retirement buddy. William Petersen plays impetuous Richard Chance (who is both a dick and wont to take chances, nominal determinism and all that) while Michael Greene plays his older buddy, a guy who gets to utter the “I’m getting too old for this shit” line two years before Danny Glover would Lethal Weaponise it.

The two men are on the trail of a devious counterfeiter, played by a young and magnetic Willem Dafoe, and en route to getting him (or not getting him – no spoilers), Friedkin and co-writer Gerald Petievich will run through pretty much the entire gamut of 1980s cop-drama cliches, including the one where the cops end up on the wrong side of the law, the one where an informant (excellent John Turturro) decides to play both sides off each other and the one where the cop goes to bed with a sexy blonde (also excellent Darlanne Fluegel) for reasons to do with not very much at all. Meanwhile 1980s stalwarts Wang Chung’s score deliver a soundtrack owing a debt to The Heat Is On (theme song from Beverly Hills Cop) and Huey Lewis and the News’s The Power of Love (Back to the Future).

It’s not what happens in To Live and Die in LA but the way it happens that’s important. Friedkin shot it all fast and usually on the first take (sometimes even while the actors thought they were still rehearsing). He has a documentary-maker’s eye for realism and an obsessive interest in process – watching Dafoe’s master forger Eric Masters printing US dollars is almost a how-to video – which was, after all, what made The French Connection and The Exorcist really fly. But he’s also got an eye for texture – the drape of a jacket, the length of a leg, the colour of a sunset, the quality of the rain in a storm, the feel of a seedy bar.

In Dafoe’s Masters we can see Friedkin inserting himself into the story. Masters was an artist before turning to forgery and at one point burns one of his paintings before getting back to the printing presses and the problem of fencing the money. The artist reduced to knock-off work. Point made, point taken.

In case we’d forgotten how good Friedkin is at action sequences, he restages the car chase from The French Connection, using techniques familiar from the 1971 movie and shifting through the gears from a frenzied drive through an industrial estate, to bouncing along the side of a railway line and over the tracks, before moving the chase into the LA storm drains and then finally getting (famously) onto the freeway, where Chance drives against the flow of traffic and massive vehicular mayhem ensues.

It’s urgent, graphic, bloody (holes-in-the head bloody) and sexy, the way Friedkin intended. There’s a neo-noir despair at its centre, echoed in the frequently shadowy cinematography of Robby Müller, who here adds Friedkin to a distinguished list of maverick directors, including Alex Cox (Repo Man), Wim Wenders (The American Friend), Barbet Schroeder (Barfly), Jim Jarmusch (Dead Man), Sally Potter (The Tango Lesson), Lars Von Trier (Dancer in the Dark) and Michael Winterbottom (24 Hour Party People).

By the end Friedkin has told an entertaining if familiar story in a dark and unfamiliar way, introduced the world to a new star – Petersen, who’d be in Manhunter the following year – and re-asserted both his artistic integrity and his forger’s credentials.

It made not the blindest bit of difference. Friedkin’s career would bump around for a long time, until, in 2011 Killer Joe reminded the world he was still good. And still here. Not, alas, any more.

To Live and Die in LA – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023