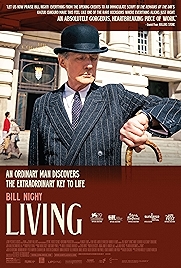

Everyone loves Bill Nighy but he’d never really looked like Oscar material – unjustly – until Living came along. Too diffident. Too stylised. Too often wearing that same blue suit. What Nighy did was so effortless that it hardly seemed like acting at all, or at least the sort of acting that Oscar likes (snot and disability, with a heartwarming character arc and a chastening moral).

Living was his big shot. It ended in valiant defeat, as we now know, with Brendan Fraser winning out against a tough shortlist that also included Austin Butler for Elvis, Colin Farrell for The Banshees of Inisherin and Paul Mescal for Aftersun. It was a case of same/same for the much-nominated Nighy with so many other awards too – often the bridesmaid, seldom the bride.

Living was his big shot because it’s an adaptation of Ikiru, a 1952 film by the revered Akira Kurosawa, who borrowed heavily from another revered director, Frank Capra, in his freewheeling adaptation of Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilyich, a novella about a man forced to confront mortality after he receives a diagnosis of terminal illness.

Kurosawa stripped much of the metaphysical content from Tolstoy’s story and Kazuo Ishiguro, who did this adaptation, sticks closely to Kurosawa and his co-writers’ template. Nighy’s character, Mr Williams, like Takashi Shimura’s in Ikiru, is a pen-pushing somebody in a faceless local government department who’s worked his way up the greasy pole by playing the game. This consists of manning bureaucratic roadblocks to ensure that nothing ever gets done. Should any member of the public ever make it as far as his office, Williams deals with them by shunting them off to another department, which will in turn shunt them off to yet another. The bureaucratic runaround.

Reserved 1950s Britain, full of men in bowler hats, is an inspired variation on the hierarchical, formal 1950s Japan of Ikiru, and Ishiguro goes not much further than that – Londonifying. As for the rest of it, Williams discovers he’s got a terminal cancer, also realises his cold son and scheming daughter-in-law actually wish he was already dead, and heads off on a life-affirming final lap of the track, first on the South Coast, where a drunken libertine (Tom Burke) show him how to have a good time, then back in London with a female office junior (Aimee Lou Wood) whose innocence and joie de vie inspire him.

Frank Capra’s sentimentality, which infused Ikiru, remains intact here, and gives Bill Nighy permission to tug on the heartstrings in what would be a shameless fashion if it were almost any other actor. In fact the whole thing is a chance for Nighy to show what he can do – grabbed with both hands. Burke isn’t in it long enough to really make much of an impact, but Aimee Lou Wood is and does. Not that long out of acting school, she’s sensationally good as the initially surprised, then flattered, then suspicious Miss Harris.

The opening titles, over colourful newsreel footage, promise a pastiche of 1950s moviemaking which director Oliver Hermanus (you might have seen his South African movie Moffie) and his DP Jamie Murray honour more in the breach than the execution. Wisely – stylistically it would have swamped the story. But Hermanus gets close and this is a carefully colour-coded affair – drabs for the oppressive home, greys for the Kafka-esque office, nostalgic, idealised pastels for the various bars, tea rooms and cinemas where Williams grabs his last moments of Living, particularly when he heads to the South Coast for his booze-fuelled epiphany.

It’s a sad and quietly heroic story, which ends, as Ikiru does, with its protagonist sitting on a child’s swing in the playground he helped get built as part of his restitutive final act. Up come the titles and up come Ralph Vaughan Williams’s Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. If it doesn’t hit you somewhere, at least just a bit, you’re probably in need of a bit of the carpe diem yourself.

Living – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2023