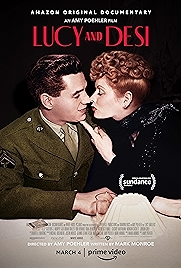

Amy Poehler’s debut documentary Lucy and Desi wants to tell the story, not unreasonably given its title, of both titan-of-TV-comedy Lucille Ball and her husband, business partner and co-star Desi Arnaz. Immediately there’s a problem. Lucy was a genuine star, Desi was not. Whatever his many talents behind the scenes, first as a musician then as a producer, they didn’t translate to the screen, and even a cursory glance at any one of Desi’s many appearances alongside his wife reveal a man who looks like he’s eager to get out of the bright lights. Not everyone can be a gifted comic actor, or wants to be. This asymmetrical twin focus is tough enough, but Lucy and Desi also wants to take in both the life and the work of the two parties. A documentary trying to head in four unequal directions at the same time is the result.

Poehler has a point. As Ball showed repeatedly in a string of sitcoms bearing her name (chiefly I Love Lucy, The Lucy Show and Here’s Lucy, though there were more in her remarkable run from the 1950s to the 1980s), Ball’s strength was her collaborative practice as well as her combative instinct (translation: not easy to work with). To Poehler’s credit, she gets about as far along her chosen fourway street as you can imagine anyone getting.

But back to the beginning. Lucille Ball was born into a family of modest means in 1911, took her first job in “showbiz” selling hamburgers at an amusement park before heading to New York aged 15 to make her way. A “dud” (her words) showgirl, she became a model, got spotted on the street and became a Goldwyn Girl in a string of movie musicals, fell in love with Hollywood and, saying yes to everything – “I didn’t care what I did… they didn’t have to ask me twice to do anything” – gradually started making a name for herself.

Desi, a Cuban exile, got his break playing in Xavier Cugat’s band and came to Hollywood via Broadway, where he learned how to turn on the charm as a conga-playing showman. Desi and Lucy met on 1940’s Too Many Girls, fell in love and married. Matched in their work ethic, both saw their early underpaid/overworked years as an apprenticeship. They were grateful for whatever came their way. Lucy’s estimation of herself was harsh – “not beautiful and not too bright” and “not a funny person” – but it made her work like a Trojan to compensate.

If you’ve seen any of the films she was in (1947’s Lured is a good example), Ball was a fine actress with a lot going for her, but she was never going to be a leading lady. And so “the Queen of the Bs”, as she was becoming known, filled in on radio. And from there she made the leap to TV, taking with her the writers and storylines that had made My Favorite Husband a radio hit and transforming it into I Love Lucy en route.

The interesting bit starts here, as Desi and Lucy set up their own production company, Desilu, to produce the show. Open to innovation, ready to grab any idea in the wind, they decide a) to shoot their show in front of live audiences (TV shows at the time generally used canned laughter) and b) to shoot them on film, to improve the quality (TV shows at the time generally went out live on the east coast, with a poor quality kinescope copy for the west).

Both choices necessitated coming up with completely new ways of working. They used three cameras – also unheard of – with studio sets next to each other. Desilu had inadvertently invented the modern TV sitcom. Shooting on film also made re-runs viable, something CBS overlooked when it inked the deal. And here is where Desilu cleaned up. They’d not only invented the modern TV sitcom but modern TV’s income model – syndication.

By 1957 Desilu had bought RKO’s studio complex – as sure a sign of TV’s ascendancy over the movies as any – and together Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz set out to show they were astute entertainment professionals with sound business brains. It was Desilu that produced Star Trek, The Untouchables and Mission Impossible.

Along the way, Poehler drawing a slight veil over Arnaz’s womanising, the two of them divorced, though on the evidence of their daughter, Lucie Arnaz Luckinbill, remained devoted to each other to the end.

Poehler has a wealth of taped audio interviews to draw on and gets useful contributions from the few talking heads she uses. Both Carol Burnett and Bette Midler benefited from the mentoring Ball gave them early on in their careers and repay her with affectionate and astute comments. Norman Lear (looking amazingly good for a man edging towards 100 years old) fights Desi’s end, to an extent, with observations on the racist reaction to a white woman marrying a Cuban, and the impact on Desi of the “dominant woman” character Lucy represented. But mostly Poehler uses clips from the old shows themselves to add commentary – when Lucy and Desi divorce in real life there’s a scene from I Love Lucy of a downcast Desi saying goodbye to his screen wife etc.

This tension – the wife as the boss – is explored and much is made of Desi’s contribution as the driving force behind Desilu but, as on screen so in life, Desi trailed along resentfully in Lucy’s wake.

The film does too, a bit. More Lucy, less Desi, I kept thinking, perhaps uncharitably, as Poehler tells the story of her and him, and how their personal and professional lives meshed. This collaborative angle – not just Lucy and Desi, but the writers and supporting stars – has been Poehler’s tentative thesis throughout. But it struggles every time Lucille Ball gangling goofball appears on screen.

Lucy and Desi – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022