Mank is the story, well known to film nerds, of the writing of Citizen Kane, for many the greatest film ever made. More exactly it’s two stories, one about writer Herman Mankiewicz dishing the dirt on press baron William Randolph Hearst (his model for press baron Charles Foster Kane) and his paramour Marion Davies, the other about director Orson Welles doing Mankiewicz out of a screen credit for his work.

Inserted almost as an afterthought is yet another story – about the socialist Upton Sinclair and his campaign to become governor of California, and how his guns were spiked by the movie studios.

Installed at a secluded cabin in the Mojave desert with a typewriter, a secretary (Lily Collins) and a minder in the shape of actor and Welles associate John Houseman (Sam Troughton), the alcoholic Mankiewicz is dried out and put under strict orders to churn out the screenplay, which Welles will later polish into the finished product. Early pages are “a bit of a jumble… a hodgepodge of talky episodes,” Houseman complains to Mank, handily nailing a problem with this film. It’s the screenplay, by Jack Fincher, father of director David. It’s verbose, explicatory and vaingloriously constructed in Citizen Kane fashion as a series of flashbacks setting out to explain the character of Mankiewicz.

This is a tragedy because this film is clearly a labour of love, gorgeously crafted by Fincher and a production team including DP Erik Messerschmidt and musicians Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross. But the screenplay’s tin ear for dialogue starts to drag all the film’s other artistic decisions into question, most obviously David Fincher’s decision to shoot the thing as a facsimile of a black and white 1940s movie, down to crackly atmospherics on the soundtrack and visual artefacts on the “film stock”. It should be immersive; it seems just cute.

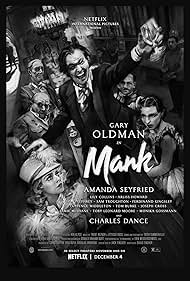

As, in flashback, we follow Mank’s glittering, booze-swamped trail through Hollywood, and his cagey relationship with Hearst (Charles Dance), Davies (Amanda Seyfried) and the mogul’s court, there’s plenty to like for lovers of old Hollywood stories – about Louis B Meyer, Irving Thalberg, Ben Hecht et al – though I suspect that the sort of people who like these sort of stories will have heard the ones we get here. The one, for example, about the Marx brothers mischievously grilling hot dogs in Irving Thalberg’s office because they were sick of his no-shows.

Lily Collins comes out of it best, as the prim but flinty British secretary delegated to keep Mankiewicz’s nose to the typewriter while he dries out and knocks out the screenplay for Kane in record time. Gary Oldman as Mank you can’t fault really, but it’s difficult to tell whether his performance is too mannered for the film or the film is too mannered for his performance. Or, again, it could just be the dialogue – Mank is funny, the screenplay keeps insisting, and while there is the odd zinger, much of his “wit” is baffling. Seeing a giraffe on Hearst’s estate while out walking with Marion, Mank demonstrates his rapier repartee by observing drily, “Now that’s sticking your neck out.” Both Oldman and Seyfried look a little embarrased.

It is a film full of unquestionably fantastic performances in minor roles – Arliss Howard is superb as the constipated conservative studio boss Louis B Meyer, Ferdinand Kingsley similarly great as Thalberg, the “Boy Wonder” head of production at MGM, and Tom Burke is persuasive in a tricky role as a silky (still young, still slim) Orson Welles. But Jack Fincher’s screenplay is most interested in the treacherous Mankiewicz’s relationship with Marion Davies – a talentless bimbo if you go along with the Citizen Kane view of Charles Foster Kane’s mistress; a sensitive, clever and wise woman devoted to her older husband and aware of the mercenary nature of Hollywood in Mank. Along with Collins, Amanda Seyfried comes out of this film best, and is pretty much perfect as Davies too.

The fact that Welles in real life denied that Marion Davies was his model for Kane’s wife, Susan, and that there were many other possible inspirations for Charles Foster Kane, that’s not addressed at all. Which somewhat torpedoes some of the claims that this film tells it like it is.

The political afterthought – the Depression and failure of capitalism, growing unrest on the streets, the rise of socialism, Upton Sinclair and the conniving of the studios to neutralise him – deserves a film all of its own but ends up shoehorned into a space already tied up in knots trying to tell other stories. Bizarrely, contrarily, it’s actually the most interesting bit of it all – “fake news” and all that.

Fincher at his best, Fight Club or The Social Network, is trenchant, urgent and playful, but Mank has none of those qualities. For all its huge budget, its costumes (“gowns” say the credits, which also prefers “screen play” to “screenplay”) and its pained attention to detail, Mank comes across like three or even four decent B movies fighting for air.

© Steve Morrissey 2020