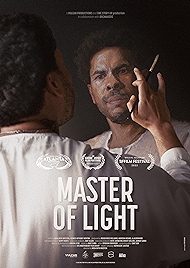

A film “by Rosa Ruth Boesten and George Anthony Morton” it says at the beginning of Master of Light. Given that Boesten is this documentary’s director and Morton its subject, that’s an unusual way of putting it.

And yet. It’s the story of a former drug dealer, a man who spent his entire 20s in prison, and how he has been saved by painting. Painting, what’s more, like the Old Masters – Morton is a big fan of Rembrandt. For a black guy with a neck tattoo there’s a certain headline-catching novelty factor right there.

If the neck tattoo and jail time seem to tell one story, Morton’s softly spoken manner and kind eyes tell another. It’s this story that Boesten most wants to tell, and she does it using Morton’s manner – gentle – and a painterly style of strongly directional lighting also owing something to the Old Masters (here and there, at any rate).

In the manner of these things, Boesten takes Morton back to Kansas City, where he grew up in “the neighbourhood drug house…” along with his mother and grandmother, both of them drug users. There he hangs with some old homies and reminisces about how it used to be, dealing on the streets and periodically getting arrested by the police. This was how these teens earned their living; it was the only life they knew. In an indication of what sort of life it was, we see Morton tending to the wounds with one of his old compadres, a guy with staples holding together huge swathes of flesh. That must have been some knife attack.

Eleven years and three months is what Morton was sentenced to, for the possession of two ounces of crack. And when he came out, the halfway house where he was sent was “in the hood… literally the worst place”. One of the themes Morton returns to repeatedly is how the system primes guys like him to fail. If it hadn’t been for the painting…

Another subject he keeps returning to is his mother, who is both a reminder of the life he has escaped and a warning about backsliding. If jail, and art, saved Morton, there is no such lifeline for his mother, who turns up in this film in one of two guises – either she’s on the phone begging her son to come and get her out of some new bail-bond or legal jam, or she’s sitting for him while he paints a tender portrait of her in oils.

“I’m carrying a tradition into the future that people like me have never been part of … it’s a beautiful tradition,” he says of his adoption of a technique developed around European physiognomies and skin tones. Morton’s quietly revolutionary agenda is to paint black people like that too.

Boesten also follows Morton to Amsterdam to see Rembrandts first hand, and in to hushed rooms where Morton gives talks to nice middle class art lovers enthralled (and validated) by stories such as his. The Ennobling Power of Art etc.

There’s a touch of the “well fancy that” about this documentary, which spends a lot of time on Morton’s personal circumstances and not enough time on his art. Prison is clearly where he developed a latent talent but this side of the story feels under-developed, leaving the other side – black guy, hood, drugs, jail – to carry more weight than its frame can really bear.

Morton’s attempt to break the cycle, so his kids/neices/nephews don’t go down the same road are touching, as is the repeated attempt to heal the rift with his mother – a late-breaking revelation (no spoilers) underlines what a herculean task this is.

“It’s gorgeous… I love it,” are the last words spoken, by Morton’s mother when she finally sees the finished painting. It is, like Boesten’s documentary, a labour of love.

Master of Light – Watch it/buy it at Amazon

I am an Amazon affiliate

© Steve Morrissey 2022